The Sisters Who Would Be Queen

The Tragedy of Mary, Katherine & Lady Jane Grey

Leanda de Lisle

For Peter, Rupert, Christian and Dominic, with love

‘Such as ruled and were queens were for the most part wicked, ungodly, superstitious, and given to idolatry and to all filthy abominations as we may see in the histories of Queen Jezebel’

THOMAS BECON 1554

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

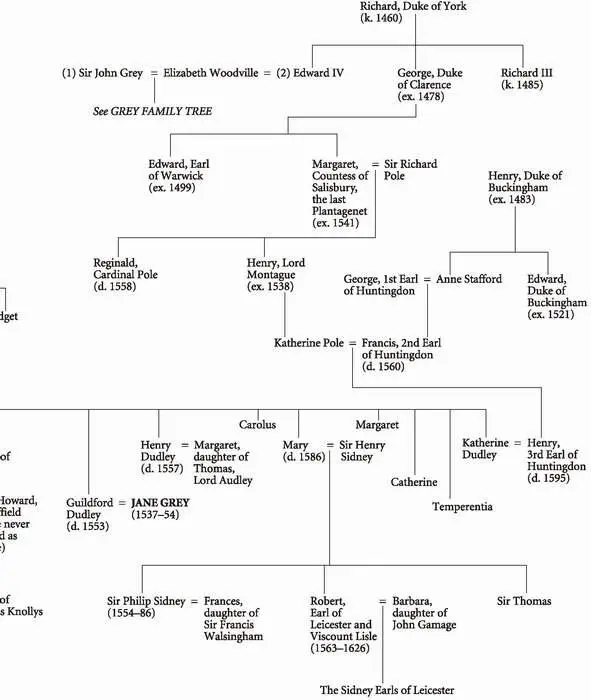

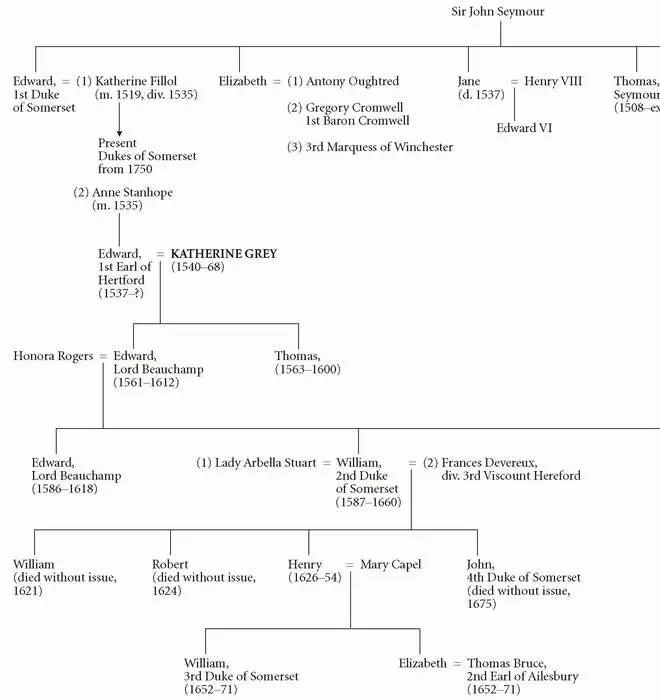

Family Trees

Prologue

PART ONE Educating Jane

Chapter I Beginning

Chapter II First Lessons

Chapter III Jane’s Wardship

Chapter IV The Example of Catherine Parr

Chapter V The Execution of Sudeley

Chapter VI Northumberland’s ‘Crew’

Chapter VII Bridling Jane

Chapter VIII Jane and Mary

PART TWO Queen and Martyr

Chapter IX No Poor Child

Chapter X A Married Woman

Chapter XI Jane the Queen

Chapter XII A Prisoner in the Tower

Chapter XIII A Fatal Revolt

PART THREE Heirs to Elizabeth

Chapter XIV Aftermath

Chapter XV Growing Up

Chapter XVI The Spanish Plot

Chapter XVII Betrothal

Chapter XVIII A Knot of Secret Might

Chapter XIX First Son

Chapter XX Parliament and Katherine’s Claim

Chapter XXI Hales’s Tempest

PART FOUR Lost Love

Chapter XXII The Lady Mary and Mr Keyes

Chapter XXIII The Clear Choice

Chapter XXIV While I Lived, Yours

Chapter XXV The Last Sister

Chapter XXVI A Return to Elizabeth’s Court

Chapter XXVII Katherine’s Sons and the Death of Elizabeth

Chapter XXVIII The Story’s End

Epilogue

Author’s Note

Notes

Bibliography

Index

Other Books By

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

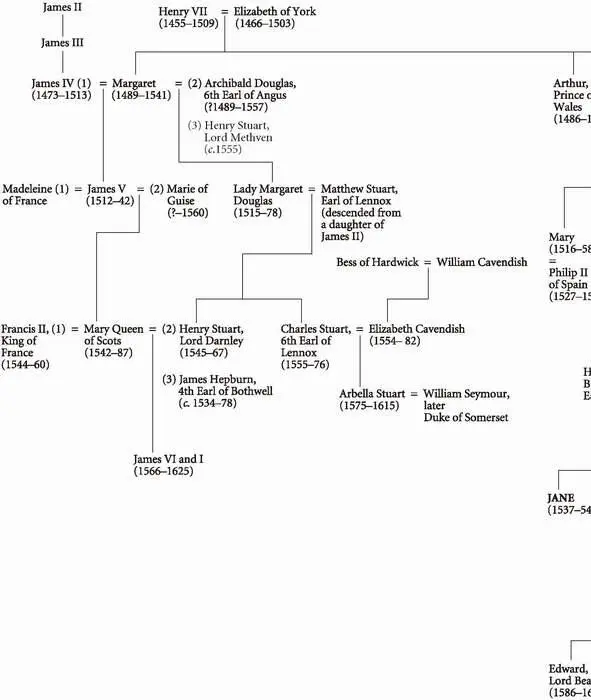

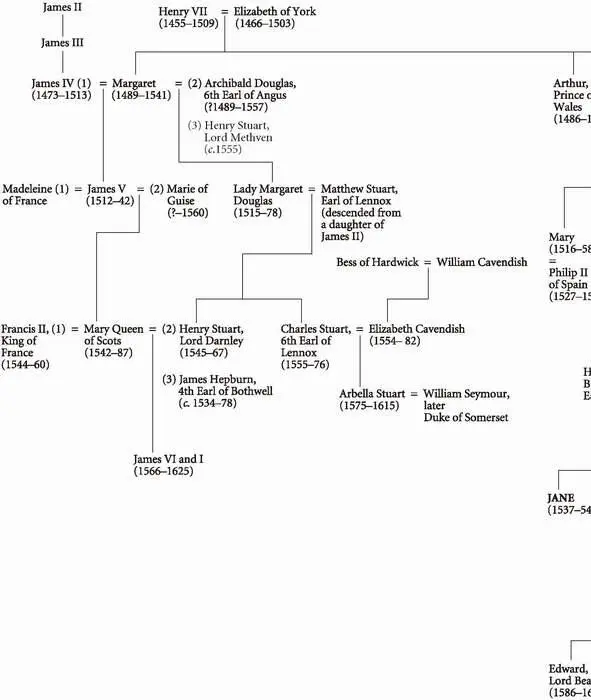

The Descendants of Henry VII

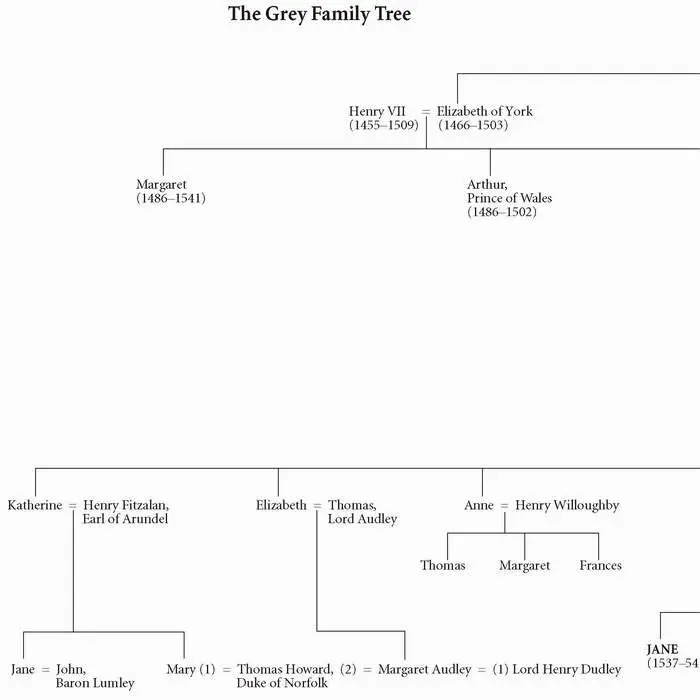

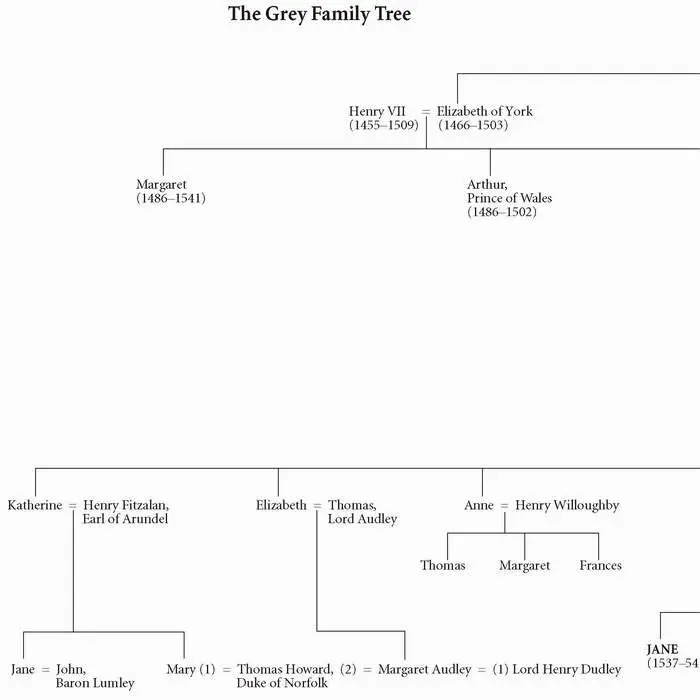

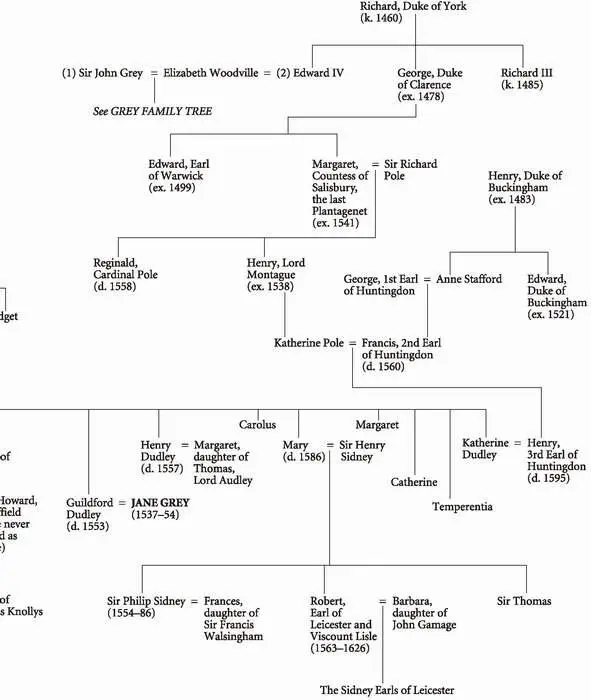

The Grey Family Tree

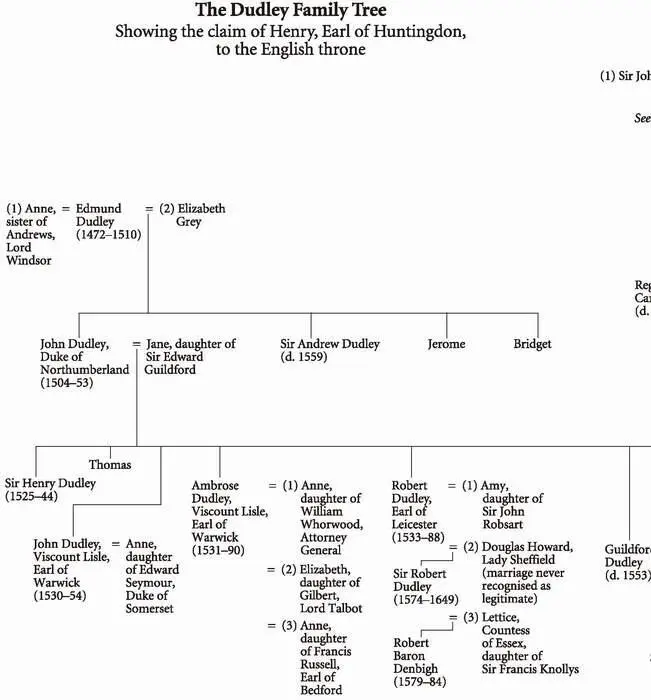

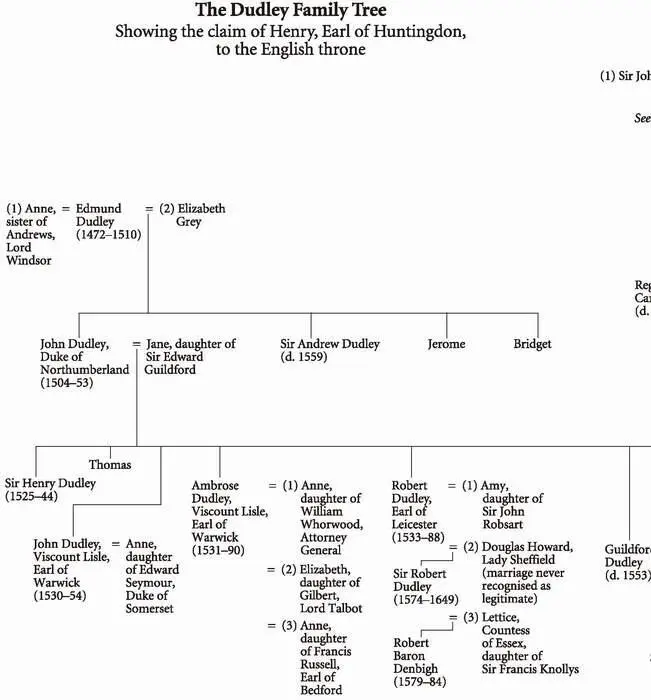

The Dudley Family TreeShowing the claim of Henry, Earl of Huntingdon, to the English throne

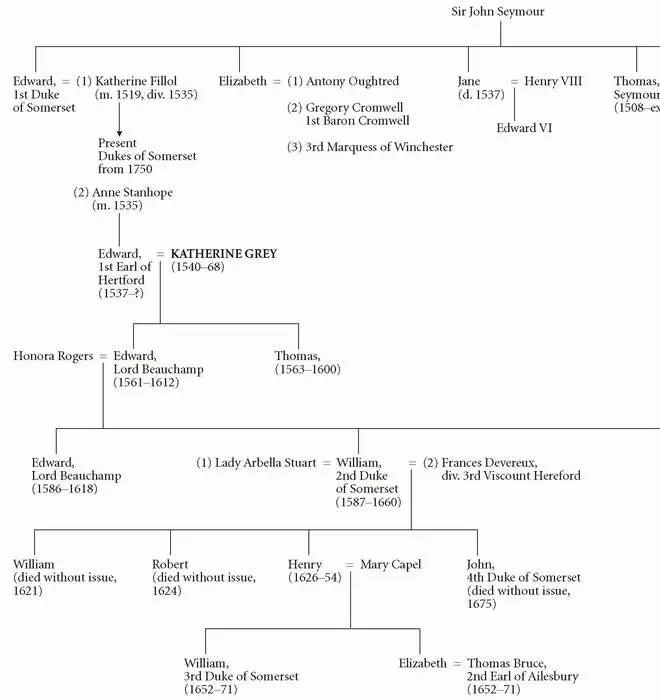

The Seymour Family Tree

God, the Prime Mover, brought peace and order to the darkness of the void as the cosmos was born. Everything, spirit or substance, was given its place according to its worth and nearness to God. Above the rocks, which enjoyed mere existence, were plants, for they enjoyed the privilege of life. Each plant also had its appointed rank. Trees were higher than moss, and oak the noblest of the trees. Superior even to the greatest tree were animals, which have appetite as well as life. Above the animals, mankind, whom God blessed with immortal souls, and they too had their degrees, according to the dues of their birth. This was the great Chain of Being, through which the Tudor universe was ordered, and at its top, under God, stood Henry VIII. It was a place he held convincingly. As he prepared for the joust on a spring day in 1524 he was still the man described by a Venetian ambassador as ‘the handsomest Prince in Christendom’. Tall and muscular with a fine complexion, the thirty-two-year-old monarch had ruled England for fifteen years and was in the prime of life. He had just had some new armour made and was looking forward to testing it at the tilt.

Henry was considered the finest jouster of his generation and the watching crowd had high expectations of the sport ahead. Attending the King on foot was his cousin, Thomas Grey, the 2nd Marquess of Dorset: his diamond and ruby badge of a Tudor rose testified to his skills as an athlete. Henry’s opponent, his brother-in-law, Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk, was, however, still more renowned. His father had been killed in 1485, holding the standard of Henry VII at the battle of Bosworth Field, where the Tudor crown was won. He had been raised at court and had married Henry’s younger sister, Mary, the beautiful widow of Louis XII of France. But Suffolk was also the King’s closest friend. The two men even looked alike and at great court tournaments dressed often in identical armour.

As Henry reached his end of the tilt, Suffolk was informed that the King was in place. The duke, however, was having trouble with his new helmet. ‘I see him not,’ Suffolk shouted out; ‘by my faith for my headpiece blocks my sight.’ Thomas Grey of Dorset, hearing nothing above the stamping of the horses, then fatefully handed the King his lance. Henry’s visor was still fastened open as he readied himself, but Suffolk’s servant, mistaking the signal warned the duke, ‘Sir, the King is coming.’ Suffolk, blinded by his helmet, spurred his horse forward. Immediately the King responded, charging with his blunted spear down the sandy list. In the crowd people spotted the King’s bare face and there were desperate shouts of ‘Hold! Hold!’; but ‘the duke neither saw nor heard, and whether the King remembered his visor was up or not, few could tell’. The thundering of hooves was followed by the clap and crack of impact. Suffolk had struck the King on the brow and his shattered lance filled the King’s head-piece with splinters. As the horses pulled up, the King still in the saddle, some in the crowd looked set to attack the duke, while others blamed Dorset for handing the King his spear too soon. Henry, in response, protested loudly that no one was at fault and, taking a spear, ran a further six courses to prove he was unhurt. But the deepest fears of the spectators still lingered.

The battle of Bosworth had followed a long period of violent disorder, fuelled by rival claimants to the throne. The eventual victor, Henry VII, had ensured the peace England now enjoyed by bequeathing his crown to an adult son, Henry VIII, who was his undisputed heir. But what would have happened if that son, the King, was now killed, or died suddenly? The fear of a return to the violence of the past was visceral. It was believed that disorder had been brought into the universe when Lucifer, the Angel of Light, had rebelled against God, and into the world by sin, when that fallen Angel tempted Eve in the Garden of Eden. Ever since, Lucifer had remained watchful for any opportunity to set loose anarchy, intending eventually to engulf earth and the heavens in chaos of unimaginable horror and evil. In the shadow of Armageddon, the question of what would happen if the King died was of vital interest - and the answer was a troubling one. Henry’s only legitimate heir was a little girl, his still carefree eight-year-old daughter Mary. Under English law it was possible for a woman to inherit the crown. Her mother, Catherine of Aragon, assumed that one day she would. But England had not yet had a Queen regnant, who ruled in her own right, and it was uncertain one could survive long.

Читать дальше