Secondly, I so enjoy the way the letter- and diary-writers tell their stories. The eighteenth-century voice, in its most formal mode, can be stately and remote; but in more relaxed correspondence, the prevailing tone is quite different. Letters between family and friends have an immediacy and a directness that rarely fail to engage the reader. Educated eighteenth-century writers were extremely candid: there were few subjects that they considered off limits. They were intensely interested in themselves and their own concerns, thinking nothing of filling page after page with detailed analyses of their health, their thoughts, and the nature of their relationships, marital, professional or political. They were tremendous gossips. Some of them were also very funny, caustic, satiric, masters (and mistresses) of an ironic tone that feels very modern in its knowingness and is still able to raise a smile after so many years.

It is very easy, reading their letters, to feel that the people who wrote them are just like us. For me, that is part of the appeal of the period, and it is, to some extent, true. But in other ways, the reality of their lives is almost impossible for contemporary readers to appreciate. In the midst of a world that seems so sophisticated and so recognisable, eighteenth-century people encountered on a daily basis experiences which would horrify a modern sensibility. Outside the well-managed homes of the better-off, extremes of poverty and the brutal and degrading treatment of the powerless and vulnerable were everywhere to be found. Even the richest families lived with the constant spectre of sickness, pain and death and could not protect themselves against the disease that decimated a nursery, the accident that felled a promising young man or the complications that killed a mother in childbirth. There is a drumbeat of darkness in all the correspondence of this period that makes a modern reader pause to give thanks for penicillin and anaesthesia.

Many of the letter-writers who so assiduously chronicled the ebb and flow of family life were women. Then, as is perhaps still the case now, it was women who worked hardest to cement the social relationships that held scattered families and friends together. One of the ways they did this was by writing to everyone in their social circle, passing on news, advice and scandal, describing their feelings and speculating on the motives and emotions of those around them. This sprawling world of the family, especially the lives of women and children, is the territory I have always found most compelling. I am fascinated by the inner life of this intimate place and am endlessly curious about how it worked. I always want to find out who was happy and who was not, how duty was balanced with self-interest, and how power worked across the generations.

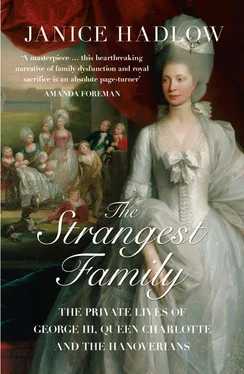

It was via these paths that I eventually came to fix upon the grandest family of them all as a suitable subject for a book. I had always been interested in George III, that much-misunderstood man, in whom apparently contradictory characteristics were so often combined: good-natured but obstinate, kind but severe, humane but unforgiving, stolid but with the occasional ability to deliver an unexpectedly sharp and penetrating insight. At first, however, it was the story of his wife and daughters that most attracted me. Queen Charlotte’s reputation was, both in her own time and afterwards, equivocal at best. In her lifetime, she endured a very bad press, excoriated by her critics as a plain, bad-tempered harridan, miserly and avaricious, interested principally in the preservation of rigid court etiquette and the taking of copious amounts of snuff. The real story, as her letters and the diaries and correspondence of those around her reveal, was rather different. Charlotte was never easy to love or, in later life, to live with, but she had a great deal to bear. She was a very clever woman in an age that found clever woman unsettling. Her intellectual appetite was unequalled by any of her successors, but could never be expressed in a way that threatened established expectations about how queens were supposed to behave. She spent nearly twenty years of her life in a state of almost constant pregnancy. In public she embraced this as the destiny of a royal wife; but, as her private correspondence makes clear, she resented the decades spent in child-bearing. Before it was crushed by the horror of the king’s illness, from which she never really recovered, and the pressures of her public role, which she sometimes found almost impossible to endure, her personality was much more attractive, sprightly, humorous and playful.

The lives of her six daughters seemed to contemporaries to contain little of interest except for the occasional whiff of scandal. They lingered unmarried for so long that they were described even by their own niece as ‘a parcel of old maids’. Their narrative is perhaps more familiar now – they were the subject of a group biography by Flora Fraser in 2004 – and it is clear that beneath the apparently bland uneventfulness of their existence, the princesses too were subject to strong emotions which were often expressed in circumstances of great personal drama. Their lives were dominated by their struggles to balance what they saw as their duty to their parents with some degree of self-determination and freedom to make their own choices. Where did the obligations they owed to their mother and father end? When – if ever – might they be allowed to follow their own desire for love and happiness? These contests were largely fought out in the secluded privacy of home – ‘the nunnery’ as one of the princesses bitterly described it – which perhaps made the sisters’ trials less visible than those of their more flamboyant brothers, but they were no less the product of powerful and often disruptive feelings.

These were extraordinary stories in themselves, and ones I longed to tell. But the more I read, the more I was convinced that the experiences of the female royals could really be appreciated only as part of a much wider canvas. The experiences of Charlotte and indeed all her children – the sons as much as the daughters – could not be understood without exploring the personality, expectations and ambitions of the king. It was George III, both as father and monarch, who established the framework and set the emotional temperature for all the relationships within the royal family. And, as I soon discovered, his ideas about how he wanted his family to work, and what he thought could be achieved if his vision were to succeed, went far beyond the happiness he hoped it would bring to his private world.

George was unlike nearly all his Hanoverian predecessors in his desire for a quiet domestic life. As a young man, he yearned for his own version of the family life he thought so many of his subjects enjoyed: an emotionally fulfilling, mutually satisfying partnership between husband and wife, and respectful but affectionate relations with their children. This was an ideal that suited his dutiful, faithful character, and which he genuinely hoped would make him and his relatives happy. But he also hoped that by changing the way the royal family lived, by turning his back on the tradition of adultery, bad faith and rancour that he believed had marked the private lives of his predecessors, he could reform the very idea of kingship itself. The values he and his wife and children embraced in private would become those which defined the monarchy’s public role. Their good behaviour would give the institution meaning and purpose, connecting it with the hopes, aspirations and expectations of the people they ruled. The benefits he hoped he and his family would enjoy as individuals by living a happy, calm and rational family life would be mirrored by a similarly positive impact on the national imagination. In his thinking about his family, for the king, the personal was always inextricably linked to the political.

Читать дальше