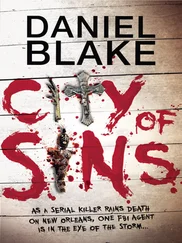

1 ...8 9 10 12 13 14 ...23 Bianca might have been his big sister, but he was still protective of her; that was the Italian male in him.

And he understood her defensiveness, too. Doctors were no different from cops – they looked out for one another. You dissed one, you dissed them all; that was how they saw it.

So they covered each other’s backs. Like most professions, medicine was in essence a small world; you never knew when you might need someone to help you out, so you didn’t go round making unnecessary enemies. And old habits died hard, even when the person you were protecting was no longer around.

‘I’m just looking for why someone might have wanted him dead,’ Beradino said.

Bianca nodded. ‘I understand. I’m sorry.’

‘No need.’

‘OK. Every time you lose a patient, you consider it a mistake, even when you know deep down you couldn’t have done anything more. That’s just the way you feel. And Mike had his fair share of those. I mean, brain surgery, the stats aren’t that great. You don’t open up someone’s skull unless things are pretty bad to start with. But those ones, I’m not counting; they’re not mistakes, not really.

‘Then there are the ones where, perhaps, if you’d done something different, you might possibly have saved them. But in those cases you don’t know till it’s too late anyway, and you can drive yourself mad if you dwell on it. If everyone’s vision was as good as their hindsight, every optician across the land would be out of work.’

‘People sue you for those ones?’

‘Sure. If you could have done something different, they’ll say you should have done. So the lawyers get involved, everyone starts slinging writs around, and if you can, you settle before it gets to court, goes public and damages your rep. Comes with the turf, doesn’t mean you’re suddenly a crappy surgeon.’

She paused again.

‘And?’ Patrese said, not unkindly.

‘And then there are the real fuck-ups.’

‘Redwine have any of those?’

She nodded. ‘One.’

The technical term was ‘wrong-site surgery’, which barely hinted at how catastrophic such incidents were, and how insultingly, ridiculously amateur they seemed.

Wrong-site surgery was, in essence, when the surgeon operated on a perfectly healthy part of the patient’s anatomy, and left the offending area untouched.

The consequences tended to fall into two categories: drastic, and fatal.

Redwine had been scheduled to remove a blood clot from the brain of Abdul Bayoumi, a professor of philosophy at the University of Pittsburgh.

It was a routine enough operation, especially for a surgeon of Redwine’s standing; he’d done hundreds in his career.

The clot had been on the left side of Bayoumi’s brain.

Redwine had cut into the right-hand side.

Only when he’d got all the way through the skull did he realize his mistake.

He’d immediately closed up the incision, made another one on the correct side, and removed the clot.

In 99 per cent of cases, that would have been it; a near-miss, a bureaucratic snafu, and a story on which the patient could dine out when he’d made a full recovery.

But Bayoumi had suffered complications – Bianca wasn’t sure of the exact details – on the side of the brain where Redwine had made the first, erroneous, incision.

The complications had spread, multiplied, and worsened.

Within six hours, he was dead.

‘How the hell can that happen?’ Beradino asked. ‘Don’t you guys,’ he caught himself – ‘sorry; isn’t it standard procedure to have a checklist or something, so this kind of thing gets caught before it occurs?’

‘Sure it is,’ Bianca said. ‘There’s a three-step procedure, the Universal Protocol, which is absolutely standard. First, you check the patient’s notes and make sure they tally with the surgery schedule. Then you use indelible markers to spot the site where the surgeon’s going to cut. Finally, the entire operating team takes a time-out before the start and agrees that this is what they’re supposed to be doing.’

‘So how can something like this happen?’

‘Because a system is only as good as the people using it.’

‘And?’

‘And in an operating theatre, the surgeon is God. He’s captain of the ship; his word goes. So if he says we cut on the left, we cut on the left. And if the notes say otherwise, who’s going to tell him, and get yelled at, or worse? Shoot the messenger, you know. Everyone stands around looking at each other, and no one does a thing.’

‘Redwine was one of these surgeons?’

‘One of them? He was the archetype. He prided himself on not marking sites, as he claimed he could always remember. He didn’t think he needed to write things down, like the rest of us mortals.’

‘Christ on a bike,’ Patrese said.

‘Don’t blaspheme, Franco,’ Beradino said instantly. ‘You know I don’t like it.’ He turned to Bianca. ‘How often does this kind of thing happen?’

‘Per month, per week, or per day?’

Patrese and Beradino looked at her in astonishment.

‘Are you serious?’ Patrese said.

‘I never joke about my work, Cicillo, you know that.’

Patrese pursed his lips and blew out; Beradino shook his head.

‘And this guy’s family – Bayoumi – they’re suing?’

‘I think so.’

‘Bayoumi.’ Beradino turned the name over, as though inspecting it. ‘Arab?’

‘Egyptian, I think.’

‘What kind of family?’

‘Wife, one son.’

‘How old?’

‘Early twenties, far as I know. Student at Pitt.’

Patrese knew instantly why Beradino was asking. Ask a bunch of Americans chosen at random to play word association with the phrase ‘young Arab man’, and it was a dollar to a dime that ‘hothead’ wouldn’t be far away.

Call it racism, call it common sense; people did both, and more, and they wouldn’t stop till white kids flew airliners into skyscrapers too.

Tuesday, October 19th. 11:24 a.m.

Dr Bayoumi’s wife – widow – Sameera lived out in Oakland, the university district. Her apartment was one of three in a large, rambling house with a porch out front and Greek columns propping up the veranda roof.

Mid-morning but with all the curtains still closed, as if to block out hope as well as light, she offered them Egyptian tea: hot, strong and, at least to the palates of two Italian-American detectives, undrinkable without three heaped spoonfuls of sugar.

She was darker-skinned than they’d imagined. Like many Egyptians, and Sudanese, she was of Nubian descent, Arab by culture rather than race.

They spoke in near-whispers, mindful of the enforced twilight and the evident numbness of Sameera’s grief.

Beradino, sensing that Sameera would expect the elder and more senior man to take the lead, did the talking.

‘As far as you knew, Mrs Bayoumi, was your husband’s operation routine?’

‘I think so.’

‘Dr Redwine didn’t seem unduly concerned, when you met him beforehand?’

‘No.’

‘And afterwards?’

‘What do you mean?’

‘How did Dr Redwine seem to you, after your husband died?’

‘I haven’t seen him since then.’

‘Not once?’

‘No.’

‘Have you tried to see him?’

‘Of course. But always, he busy. I remember something Abdul always like to say. With great power comes great responsibility. But Dr Redwine not see it like that.’

‘Would you say the hospital has been unco-operative?’

‘Yes. Very. Not just like that, blocking him from me. I ask for documents, records, and they no interested. Treat me like fly to swat. So I call lawyer.’

She handed them a glossy brochure from the firm in question, a medical malpractice specialist. Patrese glanced at it. Swanky downtown address, shots of a happy but industrious multi-ethnic workforce that wouldn’t have looked out of place in a Benetton commercial, and a commitment in bold typeface to ‘help you down the path to a better tomorrow’.

Читать дальше