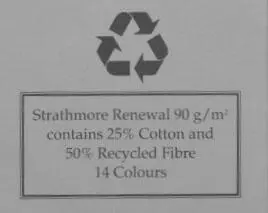

An example from G. F. Smith & Sons Ltd, paper and envelope makers, of the fibre content of their business envelopes ( courtesy G. F. Smith & Sons Ltd )

Koops published the magnificently titled Historical Account of the Substances Which have been Used to Convey Ideas from the Earliest Date to the Invention of Paper , in which he claimed that some of the pages of the book were of ‘Paper made from wood alone, the product of this country, without any intermixture of rags, waste paper, bark, straw or any other vegetable substance, from which paper might be, or has hitherto been manufactured; and of this the most ample testimony can be given’.

Testimony was indeed forthcoming, for during 1800 and 1801 Koops was granted a number of patents for paper manufacturing, including one ‘for manufacturing paper from straw, hay, thistles, waste and refuse of hemp and flax, and different kinds of wood and bark’. Attracting investors to his alternative paper-manufacturing project, Koops built a vast paper mill in London, at Westminster – the grim sight of which the William Blake scholar Keri Davies believes may have influenced Blake’s apocalyptic vision of industrialisation in his prophetic book, The Four Zoas – but within a year Koops’s creditors had closed in on him again, and by 1804 the mill had been sold off, and it was left to others to profit from paper made from wood. These others included Friedrich Gottlob Keller, the German weaver who was granted the patent for a wood-grinding machine in 1840, a machine which was then developed by Heinrich Voelter and imported to America by Albrecht Pagenstecher, founder of the first ground-wood pulp mill in the United States. Chemical wood-pulping processes, which stew wood rather than grind it – using either alkali, in the soda process, or acid, in the sulphite process – were developed during the same period, and by the mid-nineteenth century the West’s potential paper crisis had been averted: raw-material costs had fallen, production had increased, demand worldwide exploded. The Age of Paper had truly begun. Wood had saved paper.

And paper, in turn, has destroyed wood. Today, almost half of all industrially felled wood is pulped for paper, and according to green campaigners our uncontrollable appetite for the white stuff has become a threat to the entire blue planet. In medieval Britain special courts and inquisitions were held to hear the ‘pleas of the forest’, with tenants and foresters being summoned for breaches of the forest laws, including damage to timber and the poaching of venison. In a contemporary reversal of these forest eyres, activists and campaigners now call upon multinational paper companies to account for their forest-management crimes.

One of the angriest and most eloquent among the modern-day forest pleaders is the writer and activist Mandy Haggith, who argues that ‘We need to unlearn our perception of a blank page as clean, safe and natural and see it for what it really is: chemically bleached tree-mash.’ According to Haggith and many others – groups such as ForestEthics, the Dogwood Alliance and the Natural Resources Defense Council – modern papermaking has had devastating human and environmental consequences: in short and in summary, as well as causing soil erosion, flooding, and the widespread extinction of habitats and species, it has also caused poverty, social conflict, and is leading us on a long and inexorable paper trail to world apocalypse, via self-destruction. The few giant global companies that dominate the paper industry – International Paper, Georgia-Pacific, Weyerhaeuser, Kimberly-Clark – are accused of razing ancient forests, replacing them with monoculture plantations that are dependent upon chemical-based fertilisers, and polluting rivers and lakes with their industrial by-products.

The charge sheet is long and complicated, but even if the paper companies could acquit themselves entirely, and wood resources were inexhaustible, and all forests forever sustainably managed, paper manufacturing would still pose a threat to the world’s future, because the mass industrial production processes use so many other finite resources, including water, minerals, metals and fuels. ‘Making a single sheet of A4 paper,’ according to Haggith, ‘not only causes as much greenhouse gas emissions as burning a lightbulb for an hour, it also uses a mugful of water.’ (Industry figures suggest that it takes about forty thousand litres of water to make a tonne of paper, though much of that water is recycled.) With our delicious, decadent daily diet of newspapers, magazines, Post-it notes, toilet and kitchen rolls, we are guzzling down gallons of water and eating up electricity: we have grown fat and become obese on paper. In the UK, average annual paper consumption per person is around two hundred kg; in America it’s closer to three hundred kg; and in Finland – whose paper industry accounts for 15 per cent of the world’s total production – it’s even more. Consumption in China is currently a mere fifty kg per person, but gaining fast. World paper consumption is now approaching a million tonnes per day – and most of this, after its short useful life, ends up in landfill. One way or another, and indisputably according to Haggith, ‘We treat paper with utter contempt.’

Which is odd, because we absolutely love trees. In fact, we worship them – not dendrologists, but dendrolators . In The Golden Bough (1890), that massive, mad compendium of myths and rituals, James Frazer has a whole chapter on the worship of trees, listing rituals for just about every human and non-human experience, from birth to marriage to death and rebirth, ad infinitum. The Golden Bough is of course itself named after the story from the Aeneid , in which Aeneas and the Sibyl are required to present a golden bough to Charon, in order to cross the river Styx and thus gain access, through Limbo and Tartarus, to the Elysian Fields, where Aeneas is reunited with his father, Anchises. Trees grant us access to underworlds and other worlds also in Norse mythology, with Yggdrasil, the World Tree, a giant ash which connects all the worlds, and from which Odin is sacrificed by being hanged, before being resurrected and granted the gift of divine sight. Stories of special, sacred and cosmic trees abound in religion, in history and in legend: Augustine is converted under a fig tree; Newton is inspired under an apple tree; the Buddha under the Bo tree; Wordsworth ‘under this dark sycamore’, composing ‘Tintern Abbey’; and in the eighteenth century a large elm tree in Boston, the so-called Liberty Tree, became the symbol of resistance to British rule over the American colonies.

If the tree is a site of personal enlightenment and a symbol of emancipation, then woods and forests are places of enchantment that can and often do represent entire peoples, nations, and indeed the world as a whole. In Andrew Marvell’s ‘Upon Appleton House, to my Lord Fairfax’ (1651), for example, often read as an allegory on the English Civil War, the narrator takes ‘sanctuary in the wood’, where ‘The arching boughs unite between/The columns of temple green’ – the wood as a place of safety where one can take stock, rethink and re-imagine. Similarly, in Italo Calvino’s fabulous novel The Baron in the Trees (1957), set in Liguria in the eighteenth century, the young Baron Cosimo Piovasco di Rondò climbs up into a tree in order to escape his tormenting family and to gain perspective on the world: he likes it so much up there that he decides to stay.

A yearning for arboreal existence is no mere fairytale – although it is also, often, a fairytale (the tales of the Brothers Grimm, for example, feature a veritable forest of forests, so much so that they might be said to grow not from German folktales but direct from German soil). An extraordinary number of recent books celebrate trees and woodlands in near mystical fashion. Colin Tudge, in The Secret Life of Trees: How They Live and Why They Matter (2005), argues that ‘without trees our species would not have come into being at all’. Richard Mabey, in Beechcombings: The Narratives of Trees (2007), sees trees as witnesses to human history, ‘dense with time’. And Roger Deakin, in Wildwood: A Journey Through Trees (2007), provides a personal account of how trees teach us about ourselves and each other, the forest not as a mirror to nature, but the mirror of nature. ‘I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately,’ proclaimed Thoreau, long ago, in Walden, Or Life in the Woods (1854), ‘to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.’

Читать дальше