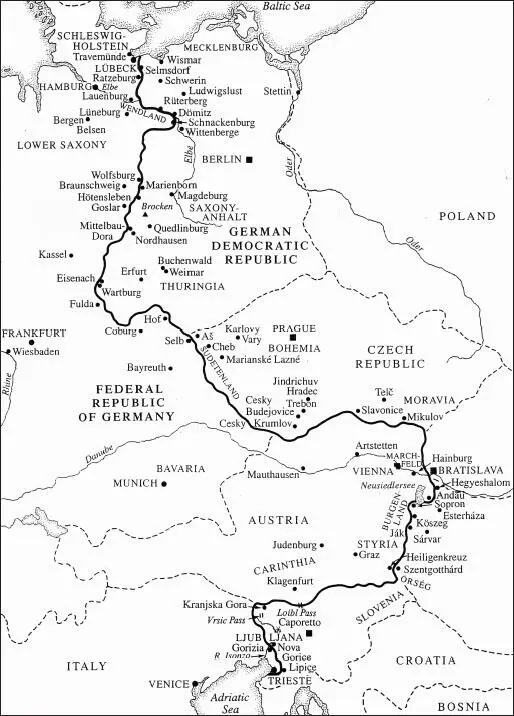

What followed this sixteenth-century revolution in mapping and map technology, in the words of Lloyd A. Brown, in The Story of Maps (1950), was ‘the greatest real estate venture of all time’. During the sixteenth, seventeenth, eighteenth, nineteenth and twentieth centuries, paper maps allowed groups and individuals not only to navigate, but also, crucially, to make plans for navigations and adventures, both great and small. What’s true for countries is true also for country estates. Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown, for example, was so-called because he could see the capabilities in a landscape; he could read it like a document, or a map. Explaining his method of garden design, Hannah More famously recounted how Brown would point a finger and announce, ‘“I make a comma and there,” pointing to another spot, “where a more decided turn is proper, I make a colon; at another part, where an interruption is desirable to break the view, a parenthesis; now a full stop, and then I begin another subject.”’ Using maps and surveys, estates could be managed, trees planted, and grand visions and ideas put into practice.

Over the past five hundred years, paper has helped to create and define landscapes, peoples and nations. Maps have assisted and determined the colonial and military explorations of the Dutch, and the French, the commercial activities of the British East India Company, and countless other enterprises. (And as with space, so time was also colonised using paper, in the form of timelines, timetables, astronomical charts, genealogies and succession lists – among the most famous and elaborate of which is the massive triumphal arch, the Ehrenpforte , designed on paper by Dürer for Maximilian I around 1516, which consists of forty-five giant folded plates.) At home as well as abroad, maps defined and legitimated places: rulers who could literally see and grasp their territories could define and defend them. The work of the Ordnance Survey, for example, begun in 1791, was a survey for the British Board of Ordnance, undertaken following the successful use of maps in the Scottish Highlands after the crushing of the Jacobite rebellion at Culloden in 1746. But it’s not all bad news. It’s not all about subjugation. If a map is a visual statement and argument about the world and our place in it – announcing both ‘I am here’ and ‘You are there’ – it can be used for good as well as for ill.

In the nineteenth century, Charles Booth famously used maps to illustrate his campaigning work on behalf of the London poor, with his street maps with their seven-colour system, from black, ‘inhabited principally by occasional labourers, loafers, and semi-criminals’ to yellow, inhabited by wealthy families who kept ‘three or more servants’. (My own family, I note, are from the black streets.) In the 1970s, Stuart McArthur’s upside-down ‘Universal Corrective Map of the World’, which shows Australia on top, became a form of national self-assertion, and the famous Peters projection, which shows all countries and continents with their relative sizes maintained, unlike Mercator’s projection, became a challenge not just to cartographers but to the international community: now that you can see the size of Africa, what are you going to do about it? In J.H. Andrews’ pithy summation, in Maps in Those Days: Cartographic Methods Before 1850 (2009), ‘Maps express beliefs about the surface of the earth’ – and, one would want to add, its inhabitants. When HMS Beagle set out from England on 27 December 1831, with a young naturalist named Charles Robert Darwin along for the ride, it was on a cartographic mission, its aim to chart South American coastlines: it returned five years later with the beginnings of a new map of human civilisation.

The map historian R.A. Skelton summarises the power and role of maps thus: ‘In the political field, maps served for the demarcation of frontiers; in the economic, for property assessment and taxation, and (eventually) as an inventory of national resources; in administration, for communications in military affairs, for both strategic and military planning, offensive and defensive.’ Maps are an integral part of that vast sub-strata of paper that underpins and still underlies the modern world, a system, in the words of the radical geographer Denis Wood, that includes ‘codes, laws, ledgers, contracts, treaties, indices, covenants, deals, agreements’. Modernity was created by, sustained by, and remains saturated in paper.

Smothered by it also. One of the traditional challenges of mapping is how to represent that which is basically a sphere on a flat surface, an example of the perennial and troubling problem of the relationship between any object and its representation. In 1931 the philosopher Alfred Korzybski delivered a paper, ‘A Non-Aristotelian System and its Necessity for Rigor in Mathematics and Physics’, at a meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, in which he remarked that ‘a map is not the territory’. But what if it were? What if a map were so accurate that it was the territory? What if the representation were perfect? In a short story by Jorge Luis Borges, ‘On Exactitude in Science’ (1946), a cartography-obsessed empire produces a 1:1 map, but then, over time, ‘Less attentive to the Study of Cartography, succeeding Generations came to judge a map of such Magnitude cumbersome.’ The giant map is left to rot, though fragments of it are to be found sheltering ‘an occasional Beast or beggar’. We are Borges’ beasts and beggars still, for all the advances in digital technology, still wrapping ourselves in paper and its representations, still struggling to distinguish between maps and the territory, still hoping against hope that our paper guide has strong folding properties, is water repellent, abrasion resistant, and will sit sturdily in the hand on a long journey. Or perhaps that’s only me.

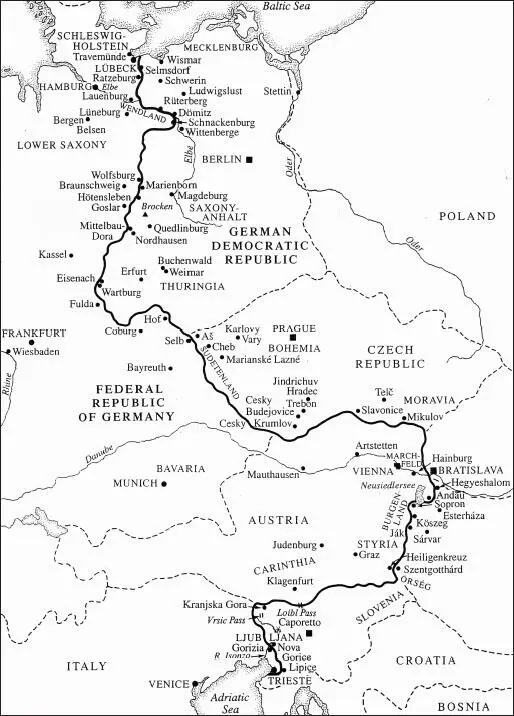

The Iron Curtain

Hand-made comb-marbled paper by Ann Muir

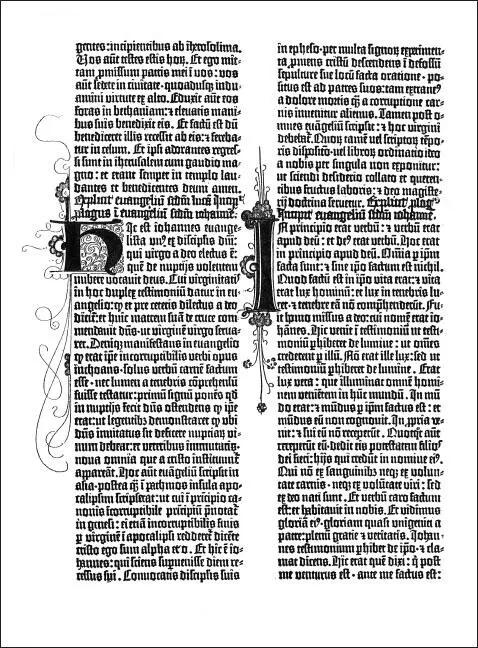

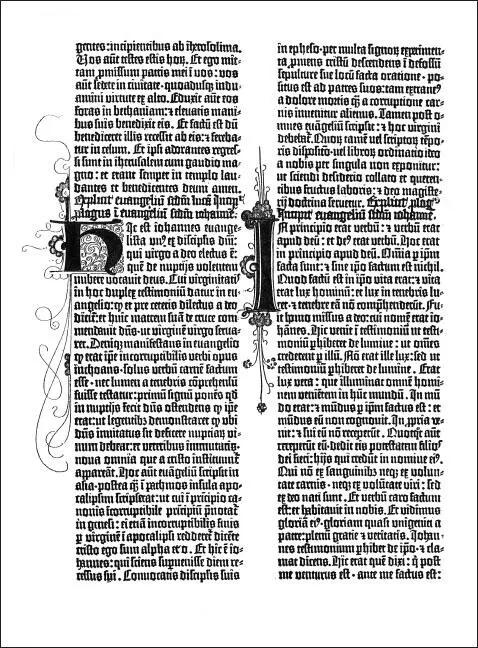

A page from Gutenberg’s forty-two-line Bible

At the beginning of his famous novel The Naked Lunch (1959), William Burroughs includes what he calls a ‘deposition: a testimony concerning a sickness’ (my copy of the book, a nice tight hardback, with original dust jacket, published by John Calder, was bought secondhand from an old junkshop in Chelmsford that I used to visit with schoolfriends at weekends in search of cheap paperback Beats, and Jean-Paul Sartre, and Albert Camus, and the Picador Richard Brautigan, and Borges, and Philip K. Dick). Burroughs is writing about his fifteen-year addiction to ‘junk’ – opium and all of its derivatives, including morphine, heroin, eukadol, pantopon, Demerol, palfium and a whole load of other stuff that he had variously smoked, eaten, sniffed, injected and inserted. ‘Junk,’ Burroughs writes, ‘is the ideal product … the ultimate merchandise. No sales talk necessary. The client will crawl through a sewer and beg to buy … The junk merchant does not sell his product to the consumer, he sells the consumer to his product … The addict … needs more and more junk to maintain a human form … [to] buy off the Monkey.’

The chances are, if you are reading this book, you are no better or worse than William S. Burroughs. The chances are, you have a serious problem: you’re an addict. You have been sold to a product. You have a monkey on your back. And that monkey is made of paper.

Читать дальше