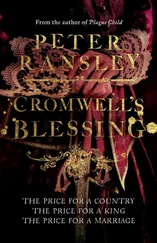

I was for Parliament – most of the London apprentices were. Our hero was Mr John Pym, leader of the opposition to the King. Mr Black printed his speeches, which breathed fire on the King’s advisers for drawing him into popery, even persuading him to sell forests to papists: the very wooden walls of our ships that protected us from Spain.

How we got hold of the speeches is a story in itself; very like old Matthew’s story of the plague child in its muddle of right and wrong. Reporting of Parliament was strictly forbidden. Allowed in as a messenger, I heard Mr Pym himself rail bitterly against the rogue printers who stole his speeches for money. For this abuse of privilege, he thundered, they should be clapped in the Tower.

An hour later Mr Ink (as I called the scrivener, for his fingers were always black with it), whom I knew worked closely with Mr Pym, was slipping that very same speech into my hands.

Yet Mr Pym, like my master, was a very godly man. They looked similar, with their stiff pointed beards, dressed in sober black, topped with starched white linen collars, except my master’s collar was plain, and Mr Pym’s finely decorated lawn. One day he called me over, staring down at me, his beard as immaculate as his linen, every hair in place as though engraved there.

‘You are fortunate to work for such a godly man as Mr Black,’ he said.

‘Yes, sir,’ I stammered, although the bruising and the blisters had scarcely faded and fortunate was not the word I would have chosen.

He took a shilling from his pocket and held out an envelope. ‘Do you know that address?’

‘Yes, sir,’ I lied.

I would have known any address for that money, even one in the foreign country of the West End, beyond the walls of the City.

‘Are you discreet?’

I did not know the meaning of the word, but again was willing to be anything for a shilling and nodded my head vigorously. Not willing to risk that the nod meant understanding, he barked: ‘Can you keep your mouth shut?’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘Do not say anything, even to your master. Is that clear?’

I was only too happy to comply. My wages were bread and cheese, my uniform and bed; the only money I ever got was from errands like this.

The letter was addressed to the Countess of Carlisle in Bedford Square, near the new Covent Garden. It was then London’s first public square. After the huddle of the City I was amazed by the spacious new brick-built houses with their porches and columns. I delivered the letter to a contemptuous footman called Jenkins who left me round the back, next to the shit heap, waiting for a reply. The heap smelt sweeter than ours, I believed then, for in it was the shit of a real Countess. Now I rather think that, unlike ours, the scavengers cleared it regular.

From Will in the Pot I learned that the Countess of Carlisle had been the mistress of the Earl of Strafford, a one-time favourite of the King, who had been executed earlier that year. She was a close friend of the Queen. So what was she doing corresponding with Mr Pym? I imagined this was a love letter I was carrying, for I was in love myself – deeply, hopelessly, with Mr Black’s daughter, Anne.

Anne laughed at my bare feet when I first came to Half Moon Court. They were big and dark as the pitch that was engrained into the skin. I flexed the huge, knobbly toes like fingers. She howled with laughter when she saw me pick up a quill between my toes, and said I was like a monkey she had seen on a gentlewoman’s shoulders. Ever after that she called me Monkey.

I tried to hate her. To my shame I cursed her, not a curse like smallpox, for I could not bear anything to happen to her skin, which was like milk and honey. The curse, Matthew had told me, must be related to the injustice, and so I cursed her feet, which were like tiny mice, scuttling in and out of her skirt, bidding them to grow even larger than mine. I scraped some dead skin from the soles of my feet and put it in her favourite shoes.

When she complained that they pinched, and her mother said she had grown out of them, I immediately regretted what I had done and spent a tortured, sleepless night praying to undo the curse. To my relief that must have worked, for, as the days passed, she made no complaints about the new shoes.

Her laughter and, even worse, her ignoring me, hurt me more than any blow I ever received in that place. According to Will in the Pot, who was an expert in such matters, I was suffering from the very worst type of love: unrequited love.

Yet it was not always so. There was a time, the first autumn I was there, when we became as close as two children ever could be. In September, towards the end of the third week, my simnel cake appeared on the doorstep. It seemed to everyone a most mysterious thing, but, of course, it was no surprise to me. The will o’ the wisps could transport such a cake in a trice. For George, it confirmed I had a pact with the devil and he would not touch a crumb. Sarah said there were good will o’ the wisps and bad, and the cake was so delicious it had been baked by good ones. I believe she began to rub pig-fat in my bruises from the moment she licked the last crumbs from her fingers. Mrs Black consulted her astrologer, who told her the cake had been stolen, and she looked at me with deep suspicion. Mr Black, whose common sense contrasted starkly with his wife’s superstition, boomed irritably: ‘How can it be stolen, Elizabeth, when the boy’s name is on it?’

Anne was first jealous – she never had such a cake – then intrigued. We began to play together. It started as mockery, but when she found I could tell the stories Matthew had told me of foreign lands, great ships and elephants and parrots, we used to hide together behind the apple tree in the centre of the court, or in the paper store. This went on for two idyllic months until, one misty autumn day we heard the rattle and braking squeal of a Hackney hell-cart stopping in the court. We ran out of the shop to gape at it. I took Anne’s hand, with a shiver of apprehension.

Out of the coach stepped a gentleman. Through the swirling fog I saw a livid scar, running from the top of his cheek and down his neck to bury itself under his collar. He stopped to glare at us. Mr Black came out and shouted to us to come in immediately. Anne ran to him but, remembering Matthew’s warning, and fearing the man with the scar had come to me for the pendant my father had stolen, I fled out of the court and hid the rest of the day in Smithfield, among the poor searching for offal discarded by the butchers.

I was flogged for that and told not to play with Anne. That only increased my desire to see her, but it was then that her haughtiness and her cruel jokes really began. I still kept the memory of that autumn, but as the years passed and she became more and more beautiful, like a gradually opening flower, and more and more distant, the memory faded until I began to wonder if it had ever happened, or whether it was just a story I was making up to comfort myself.

So there I was at sixteen, hopelessly in love, knowing nothing and caring less about the speeches I was carrying, except that I must beat the other messengers at the same game. Flapping the speech to dry it, I would run from Westminster, through the narrow streets, past the grim shape of Newgate Prison until, panting for breath through the stink of Smithfield, I would at last reach Half Moon Court where we all lived and worked in the narrow Flemish wall house with its jutting gable and creaking sign: RB with a yellow half-moon. My master would seize the copy and George his composing stick and I would prepare the press. So it was and seemed it always would be, until one momentous day.

It was November, dark as pitch, the air a fine drizzle carrying the smell of the coal clouds that hung over London when people began to stoke their winter fires in earnest. The shops and stalls in Westminster Hall, where they jostled for trade next to the law courts, were long closed. I hung about with other messengers, waiting for the House to finish its day’s business. Unusually, no Members had gone home. Some of the messengers did, or repaired to the Pot. I crawled into a corner, pulled a discarded sack over myself and dozed. Distant shouting woke me. A watchman was calling the hour of midnight. The shouting was coming from the House. There was no official on the door, and I crept into the lobby.

Читать дальше