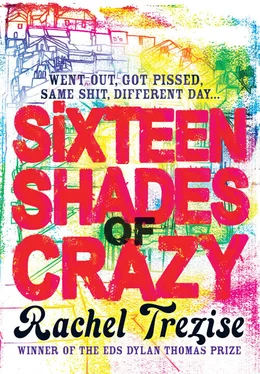

Sixteen Shades of Crazy

Rachel Trezise

For Gwyn Thomas (1913–1981)

‘Perhaps when we find ourselves wanting everything, it is because we are dangerously near to wanting nothing.’

Sylvia Plath

Cover Page

Title Page Sixteen Shades of Crazy Rachel Trezise

Dedication For Gwyn Thomas (1913–1981)

Epigraph ‘Perhaps when we find ourselves wanting everything, it is because we are dangerously near to wanting nothing.’ Sylvia Plath

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

Acknowledgements

Also by Rachel Trezise

Copyright

About the Publisher

They looked like any other group of twenty- and thirty-somethings, living the salad days of their lives, organs plump and red and juicy like the insides of ripe tomatoes, minds crisp like iceberg lettuce, sex powerful and biting like onion. Just another Saturday night at the Pump House, laughing big belly laughs, torsos bowed against the edge of the table as they concealed their illicit activities from the bar-staff, treasure moving around as if they were playing pass-the-parcel, the smell of perfume and alcohol shrouding their bodies like vinaigrette.

Ellie held the baggie in her fingers, fiddling with the knot, the plastic slippery with perspiration. Nowadays, street dealers were only concerned with their fleeting profits. There was no time for presentation. Nobody used paper wraps any more. She pushed her fingertip into the powder, kept it there for as long as it was polite, maybe longer, then smeared it over her taste buds, absorbing the sweet, glucosic tang.

‘What do they call this in America?’ she said, cheeks already tingling with anticipation. The south Wales valleys had been empty of soft drugs for eighteen months, no amphetamine, no MDMA. The new police chief had declared war on the B and C classes. Zero-tolerance policies sent all of the Drug Squad’s manpower to intercept shipments of party-starters in Bristol, while savvy London traffickers cruised the M4, Mercedes loaded with kilo packages of Afghan opiates. The skeletons of mining towns were populated by zombies, kids so thin and hopeless the wind would blow them over. Smackheads congregated in the gulleys, needles poised; the way women used to meet for chapel with their leather-bound bibles, honest-to-goodness recreational users left with nothing.

Ellie felt like an adolescent again, doing drugs for the very first time, a glorious thrill in her blood. ‘Is it crystal meth?’ she said, ‘or is that something totally different?’

Rhiannon snatched the baggie and balanced it in her lap. ‘Ooh cares?’ she said. She sprinkled a pinch of the powder into her wineglass. It was Rhiannon’s special wineglass, an unusual, egg-cup-shaped goblet that she demanded on every visit. She reached for another thumbful of the powder, her enthusiasm forcing the bag into the dip between her bare legs, an inch away from the hem of her new miniskirt. She was closer to forty than thirty; too old to wear that skirt, a shadow of a moustache on her top lip. Her hair was black, short and spiky, her eyes a soft, bovine brown. She had a huge laugh, like a drag artist’s. One of the stories about Rhiannon was that she’d been walking through Cardiff at three in the morning when some Grangetown wide-boy tried to drag her into an alley. She’d pulled a knife out of her handbag and slashed the tip of his nose clean off, left him for dead. It gave her a precarious allure that attracted weak men – men like Marc, who wanted to be neglected. There were lots of stories about Rhiannon, every one of them involving the opposite sex. Andy reckoned she’d married an octogenarian at eighteen, given him a heart attack in the bedroom; something he’d heard on a building site in Bridgend. The locals on the Dinham Estate said she’d made a pornographic video with Tommy Chippy for thirty quid, some of them swore they’d seen it; Rhiannon lying naked across the counter, eyes blacked out with tape, deep-fat fryers sizzling away in the background. All Ellie knew for sure was that she was a manipulative bitch; she hated women and women hated her.

‘Billy Whizz we call it in Wales,’ she said, hooting. ‘That’s where ewe live, El. Wales.’ She never overlooked an opportunity to remind Ellie where she was, because she knew Ellie wanted to be elsewhere, beneath the skyscrapers of New York. Rhiannon had resigned herself to a monotonous existence in the Welsh gutter, and no one else was allowed to look up at the stars.

The pub door opened. Rhiannon quickly balled the plastic into her fist. Big Barry the Disco came in and heaved his amplifier towards the squat stage, sweat stains forming under his yellow trouser braces. ‘The bloody prodigals’ return again, is it?’ he said as he shuffled past the boys.

Marc took the parcel from Rhiannon and hurriedly opened it on the table. ‘Just what the doctor ordered,’ he said, rubbing his hands together, a grin from ear to ear. He was wearing the same Liverpool football jersey he always wore, his chocolate-colour hair clipped close to his skull, receding quickly at the forehead. He was a genial man, the bassist and lead singer of a punk band called The Boobs. They’d been on a toilet circuit tour of Scotland, sleeping on the hard floor of their Transit van for six weeks, fighting for space amongst their beaten up guitars and drum-kit. They did this every five months or so, despite the lack of a record company, a tour agent, or even a cult fan base. They tossed every pound they made into the venture, as though their lives depended on it, and in Aberalaw their absence gave them the illusion of success. The stupid hacks at the local newspaper seemed to think they spent half of the year in their Malibu beach homes. Old women approached Ellie in the post office and asked her, ‘How are your Boobs doing?’

The band had got home earlier that day to the news that John Peel had listened to a demo they’d thrown at him through a backstage fence at last year’s Glastonbury Festival. He’d invited them to record a live session for the radio. Marc was happy as hell. He scoffed a whole gram of the powder, chasing it around his mouth with his roving tongue.

‘Sweetheart!’ Rhiannon barked, seizing the baggie from his hand and pushing it along the table. ‘Take it easy, will ewe? Ewe’re tiling the downstairs toilet tomorrow, remember?’

‘There’s hardly any left now,’ Griff said. Griff was the drummer, a fat, proud man with neon-orange hair; the bumptious disposition of a spoiled 12-year-old. His mother still made him corned-beef pie and salmon sandwiches to take-out on the road. He sullenly rubbed a small rock into his gum and then wiped his fingers on his check shirt, keeping the baggie in his hand, ensuring he had an audience for what he was about to say. Like a schoolboy carrying clecks to the dictatorial teacher, he looked sideways at Rhiannon. ‘He’s been a total arsehole all fucking tour,’ he said. ‘He stole a tray of muffins from Glasgow Services and kept them all to himself. He ate every bastard one and there were forty-eight of the fuckers. The only reason I’m staying in the band is because of this Peel session.’ He was always threatening to quit, and never did. ‘Should have seen the women in Scotland though,’ he said. ‘Lapped it up, they did.’

Читать дальше