‘I can’t see what good it would be if Mr Brooks did talk to me,’ said Lise, who had only been recruited three days earlier, ‘I don’t know anything.’

Vi replied that it was hard on those in positions of responsibility, like RPD, if they didn’t drink, and didn’t go to confession.

‘Are you a Catholic then?’

‘No, but I’ve heard people say that.’

Vi herself had only been at BH for six months, but since she was getting on for nineteen she was frequently asked to explain things to those who knew even less.

‘I daresay you’ve got it wrong,’ she added, being patient with Lise, who was pretty, but shapeless, crumpled and depressed. ‘He won’t jump on you, it’s only a matter of listening.’

‘Hasn’t he got a secretary?’

‘Yes, Mrs Milne, but she’s an Old Servant.’

Even after three days, Lise could understand this.

‘Or a wife? Isn’t he married?’

‘Of course he’s married. He lives in Streatham, he has a nice home on Streatham Common. He doesn’t get back there much, none of the higher grades do. It’s non-stop for them, it seems.’

‘Have you ever seen Mrs Brooks?’

‘No.’

‘How do you know his home is nice, then?’

Vi did not answer, and Lise turned the information she had been given so far slowly over in her mind.

‘He sounds like a selfish shit to me.’

‘I’ve told you how it is, he thinks people under twenty are more receptive. I don’t know why he thinks that. He just tries pouring out his worries to all of us in turn.’

‘Has he poured them out to Della?’

‘Well, perhaps not Della.’

‘What happens if you’re not much good at listening? Does he get rid of you?’

Vi explained that some of the girls had asked for transfers because they wanted to be Junior Programme Engineers, who helped with the actual transmissions. That hadn’t been in any way the fault of RPD. Wishing that she didn’t have to explain matters which would only become clear, if at all, through experience, she checked her watch with the wall clock. An extract from the Prime Minister was wanted for the mid-day news, 1’42” in, cue Humanity, rather than legality, must be our guide .

‘By the way, he’ll tell you that your face reminds him of another face he’s seen somewhere – an elusive type of beauty, rather elusive anyway, it might have been a picture somewhere or other, or a photograph, or something in history, or something, but anyway he can’t quite place it.’

Lise seemed to brighten a little.

‘Won’t he ever remember?’

‘Sometimes he appeals to Mrs Milne, but she doesn’t know either. No, his memory lets him down at that point. But he’ll probably put you on the Department’s Indispensable Emergency Personnel List. That’s the people he wants close to him in case of invasion. We’d be besieged, you see, if that happened. They’re going to barricade both ends of Langham Place. If you’re on the list you’d transfer then to the Defence Rooms in the sub-basement and you can draw a standard issue of towel, soap and bedding for the duration. Then there was a memo round about hand grenades.’

Lise opened her eyes wide and let the tears slide out, without looking any less pretty. Vi, however, was broadminded, and overlooked such things.

‘My boy’s in the Merchant Navy,’ she said, perceiving the real nature of the trouble. ‘What about yours?’

‘He’s in France, he’s with the French army. He is French.’

‘That’s not so good.’

Their thoughts moved separately to what must be kept out of them, helpless waves of flesh against metal and salt water. Vi imagined the soundless fall of a telegram through the letter-box. Her mother would say it was just the same as last time but worse because in those days people seemed more human somehow and the postman was a real friend and knew everyone on his round.

‘What’s his name, then?’

‘Frédé. I’m partly French myself, did they tell you?’

‘Well, that can’t be helped now.’ Vi searched for the right consolation. ‘Don’t worry if you get put on the IEP List. You won’t stay there long. It keeps changing.’

Mrs Milne rang down. ‘Is Miss Bernard there? Have I the name correct by the way? We’re becoming quite a League of Nations. As she is new to the Department, RPD would like to see her for a few minutes when she comes off shift.’

‘We haven’t even gone on yet.’

Mrs Milne was accustomed to relax a little with Vi.

‘We’re having a tiresome day, all these directives, why can’t they leave us to go quietly on with our business which we know like the back of our hand. Tell Miss Bernard not to worry about her evening meal, I’ve been asked to see to a double order of sandwiches.’ Lise was not listening, but recalled Vi to the point she had understood best.

‘If Mr Brooks says he thinks I’m beautiful, will he mean it?’

‘He means everything he says at the time.’

There was always time for conversations of this kind, and of every kind, at Broadcasting House. The very idea of Continuity, words and music succeeding each other without a break except for a cough or a shuffle or some mistake eagerly welcomed by the indulgent public, seemed to affect everyone down to the humblest employee, the filers of Scripts as Broadcast and the fillers-up of glasses of water, so that all in turn could be seen forming close groups, in the canteen, on the seven floors of corridors, beside the basement ticker-tapes, in the washrooms, in the studios, talking, talking to each other, and usually about each other, until the very last moment when the notice SILENCE: ON THE AIR forbade.

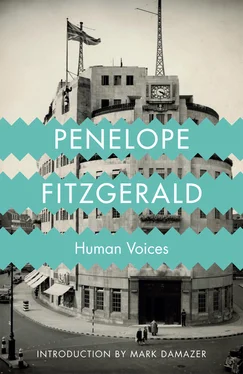

The gossip of the seven decks increased the resemblance of the great building to a liner, which the designers had always intended. BH stood headed on a fixed course south. With the best engineers in the world, and a crew varying between the intensely respectable and the barely sane, it looked ready to scorn any disaster of less than Titanic scale. Since the outbreak of war damp sandbags had lapped it round, but once inside the bronze doors, the airs of cooking from the deep hold suggested more strongly than ever a cruise on the Queen Mary. At night, with all its blazing portholes blacked out, it towered over a flotilla of taxis, each dropping off a speaker or two.

By the spring of 1940 there had been a number of castaways. During the early weeks of evacuation Variety, Features and Drama had all been abandoned in distant parts of the country, while the majestic headquarters was left to utter wartime instructions, speeches, talks and news.

Since March the lifts below the third floor had been halted as an economy measure, so that the first three staircases became yet another meeting place. Few nowadays were ever to be found in their offices. An instinct, or perhaps a rapidly acquired characteristic, told the employees how to find each other. On the other hand, in this constant circulation much was lost. The corridors were full of talks producers without speakers, speakers without scripts, scripts which by a clerical error contained the wrong words or no words at all. The air seemed alive with urgency and worry.

Recordings, above all, were apt to be mislaid. They looked alike, all 78s, aluminium discs coated on one side with acetate whose pungent rankness was the true smell of the BBC’s war. It was rumoured that the Germans were able to record on tapes coated with ferrous oxide and that this idea might have commercial possibilities in the future, but only the engineers and RPD himself believed this.

‘It won’t catch on,’ the office supervisor told Mrs Milne. ‘You could never get attached to them.’

‘That’s true,’ Mrs Milne said. ‘I loved my record of Charles Trenet singing J’ai ta main . I died the death when it fell into the river at Henley. The public will never get to feel like that about lengths of tape.’

Читать дальше