In memory of

THE POETRY BOOKSHOP

Contents

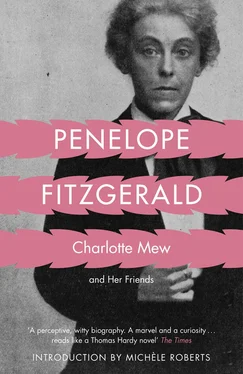

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Preface

Introduction

1: The Day of Eyes

2: Love between Women

3: Lotti

4: ‘These I Shall See’

5: A Yellow Book Woman

6: The China Bowl

7: Nunhead and St Gildas

8: Rue Chateaubriand

9: The Quiet House

10: The Farmer’s Bride

11: Mrs Sappho

12: May Sinclair

13: ‘Never Confess’

14: The Poetry Bookshop

15: Alida

16: ‘J’ai passé par là’

17: Sydney

18: The Shade-Catchers

19: Delancey Street

20: The Loss of a Mother

21: The Loss of a Sister

22: Fin de Fête

Selected Poems of Charlotte Mew

The Farmer’s Bride

In Nunhead Cemetery

The Changeling

Ken

A Quoi Bon Dire

The Quiet House

Madeleine in Church

The Shade-Catchers

Saturday Market

Sea Love

From a Window

Not for that City

Fin de Fête

I so liked Spring

The Trees Are Down

Appendix: A Note on the Poetry Bookshop Rhyme Sheets

Select Bibliography

Index

Acknowledgements

Notes and References

Also by the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Preface by Hermione Lee, Advisory Editor

When Penelope Fitzgerald unexpectedly won the Booker Prize with Offshore , in 1979, at the age of sixty-three, she said to her friends: ‘I knew I was an outsider.’ The people she wrote about in her novels and biographies were outsiders, too: misfits, romantic artists, hopeful failures, misunderstood lovers, orphans and oddities. She was drawn to unsettled characters who lived on the edges. She wrote about the vulnerable and the unprivileged, children, women trying to cope on their own, gentle, muddled, unsuccessful men. Her view of the world was that it divided into ‘exterminators’ and ‘exterminatees’. She would say: ‘I am drawn to people who seem to have been born defeated or even profoundly lost.’ She was a humorous writer with a tragic sense of life.

Outsiders in literature were close to her heart, too. She was fond of underrated, idiosyncratic writers with distinctive voices, like the novelist J. L. Carr, or Harold Monro of the Poetry Bookshop, or the remarkable and tragic poet Charlotte Mew. The publisher Virago’s enterprise of bringing neglected women writers back to life appealed to her, and under their imprint she championed the nineteenth-century novelist Margaret Oliphant. She enjoyed eccentrics like Stevie Smith. She liked writers, and people, who stood at an odd angle to the world. The child of an unusual, literary, middle-class English family, she inherited the Evangelical principles of her bishop grandfathers and the qualities of her Knox father and uncles: integrity, austerity, understatement, brilliance and a laconic, wry sense of humour.

She did not expect success, though she knew her own worth. Her writing career was not a usual one. She began publishing late in her life, around sixty, and in twenty years she published nine novels, three biographies and many essays and reviews. She changed publisher four times when she started publishing, before settling with Collins, and she never had an agent to look after her interests, though her publishers mostly became her friends and advocates. She was a dark horse, whose Booker Prize, with her third novel, was a surprise to everyone. But, by the end of her life, she had been shortlisted for it several times, had won a number of other British prizes, was a well-known figure on the literary scene, and became famous, at eighty, with the publication of The Blue Flower and its winning, in the United States, the National Book Critics Circle Award.

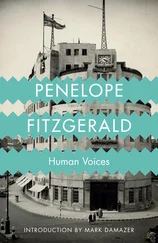

Yet she always had a quiet reputation. She was a novelist with a passionate following of careful readers, not a big name. She wrote compact, subtle novels. They are funny, but they are also dark. They are eloquent and clear, but also elusive and indirect. They leave a great deal unsaid. Whether she was drawing on the experiences of her own life – working for the BBC in the Blitz, helping to make a go of a small-town Suffolk bookshop, living on a leaky barge on the Thames in the 1960s, teaching children at a stage-school – or, in her last four great novels, going back in time and sometimes out of England to historical periods which she evoked with astonishing authenticity – she created whole worlds with striking economy. Her books inhabit a small space, but seem, magically, to reach out beyond it.

After her death at eighty-three, in 2000, there might have been a danger of this extraordinary voice fading away into silence and neglect. But she has been kept from oblivion by her executors and her admirers. The posthumous publication of her stories, essays and letters has now been followed by a biography ( Penelope Fitzgerald: A Life , by Hermione Lee, Chatto & Windus, 2013), and by these very welcome reissues of her work. The fine writers who have done introductions to these new editions show what a distinguished following she has. I hope that many new readers will now discover, and fall in love with, the work of one of the most spellbinding English novelists of the twentieth century.

Hermione Lee

2013

A true poet is first of all appreciated by his or her peer group. Critical recognition usually arrives afterwards. Charlotte Mew’s work was admired by writer contemporaries such as Siegfried Sassoon, Thomas Hardy and Virginia Woolf. Hardy said: ‘She is far and away the best living woman poet, who will be read when others are forgotten.’ Virginia Woolf said: ‘I think her very good and interesting and unlike anyone else.’

Mew’s words, coming powerfully alive on the page, also electrified audiences when she read her poems aloud. Penelope Fitzgerald, writing this biography, comments: ‘she seemed not so much to be acting or reciting as a medium’s body taken over by a distinct personality.’ Poetry in performance was relished in the early twentieth century as it is now, a hundred years later. The equivalent of our open mic poetry slam happened in the Poetry Bookshop in Bloomsbury, decorated with hand-coloured poetry posters, hung with curtains of sacking. People packed into the upstairs room and listened by candlelight. Between 1913 and 1920 you could attend readings by writers as diverse as Rupert Brooke, D. H. Lawrence, Edith Sitwell, Eleanor Farjeon, Anna Wickham and W. B. Yeats (among many others). Alida Monro did much of the work of the bookshop, alongside her poetry-publisher husband Harold. She often gave readings of the work of absent poets. She loved Mew’s poems, and in November 1915 invited Mew to come and hear her read them. Thus their long friendship began.

Mew, signalling her originality and difference through her words, also did so through her hoarse voice and her distinctive clothes. A tiny figure in a plain dark coat and skirt, severely cut, she sported a white shirt and black cravat, red stockings on occasion, and wore her hair cut short. She rolled her own cigarettes. She had an oval face, and huge eyes, which blaze out at us from her photographs.

Читать дальше