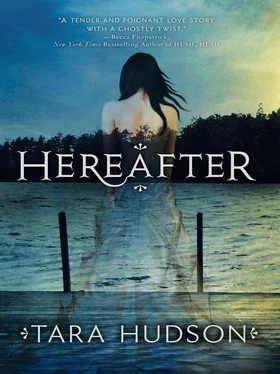

As he got closer, the screams from the shore grew louder. In them I could almost make out a rational thread of conversation concerning the plan to pull him out of the river.

But really, I wasn’t listening to the people on the shore. I was watching the boy swim, closer than I’d ever watched anything in my existence. I found myself praying for the first time since my death. Praying that he made it safely to the shore; praying that he didn’t give up and let the current take him.

“Please,” I whispered as I followed him. “Please, let him make it.”

This boy proved much stronger than I ever had. For several more agonizing minutes, he fought his way through the current. Finally, he was close enough so that someone was able to grab his arm and half swim, half drag him to the shore.

Cries of both joy and fear rose up from the crowd that had gathered on the grass embankment and the bridge above us. A man, the one who had pulled the boy from the water, stretched the boy out upon the muddy red riverbank. As I rose out of the water and walked onto the shore, I could see the man flutter his hands over the boy’s body, checking for some sign of life.

The boy instantly rolled over, coughed once, and began to vomit water. Audible sighs of relief rose up from the crowd. Their faces were illuminated by headlights from the cars parked in a jumble on the grass as well as on the bridge. The onlookers’ expressions varied from tense to excited to scared.

“Josh. Josh,” they called like a chorus.

They all seemed to know his name.

It was then that I noticed the multicolored flash of lights coming from the emergency vehicles that had formed their own sort of crowd behind the bystanders on the bridge. Within what seemed like only seconds, two uniformed paramedics had made their way down the embankment and knelt beside the boy, doing their own, more effective sort of fluttering over him. Within less than a minute after that, the boy—my boy, if I was honest in my suddenly possessive thoughts—was placed on a gurney and hoisted across the bank, then up toward an ambulance. The crowd surged forward with the paramedics, and I lost sight of him.

That should have been the end of the ordeal. Yet I couldn’t stand still. I couldn’t watch strangers take away the only living person to see me. My boy. My Josh.

Determined, I pushed through the crowd. They couldn’t see or feel me, of course, but I still had to fight to find a clear path.

By some miracle I made it through. I shoved in between two figures and suddenly found myself at the side of the gurney just as the paramedics began to raise its wheels so they could slide it and its passenger into the ambulance.

I leaned over the boy. He looked pale in the moonlight, his face gaunt and drawn. For some reason I had to hold back a sob.

“Josh?” I moaned, unsure of what to do. Unsure of everything.

He opened his eyes then. Dark-colored eyes—too dark a color to identify at night. He looked at me and held my gaze in the moment before the paramedics moved him out of my sight, possibly forever.

“Joshua,” he croaked, his voice rough from the river water. “Call me Joshua.”

Then the gurney was shoved into the ambulance, the doors slammed shut, and he was gone.

I stood there on the riverbank, motionless. Some of the onlookers remained after the departure of the ambulance, milling around to discuss what I could only assume was the near tragedy. I barely noticed when the last member of the crowd left and the last set of headlights disappeared into the darkness of the night. I wasn’t really paying enough attention to hear or see anything going on around me.

What I saw instead were his eyes, looking right into mine. What I heard was his voice … talking to me? Yes, I’m sure he’d been talking to me. No one had asked him to identify himself as they loaded him into the ambulance. He’d had no reason to give his name to anyone but me. Most of the crowd seemed to know him. Maybe they’d known him all his life. Maybe they’d sensed, as I had, how important he was.

Of course I knew his importance now. I knew it deep in my suddenly very awake core. I knew nothing about him—not his age, his last name, the way his voice would sound if it spoke my name. But I knew things had changed for me. They had changed forever.

Two days passed.

Their passage, although probably not remarkable to the living, was extraordinary to me. I’d never really had a reason to count the passing days. The sun’s rising and setting had no effect on me except to obscure my vision at night. I didn’t need sleep, and my lack of company in daylight didn’t change at sunset. When the nightmares had begun—wrenching me from wakefulness into unconscious terror and then unfamiliar daylight—I’d lost the will to mark time altogether.

Until now.

Now I couldn’t stop counting each lonely moment as it passed.

On the first night, while I watched the ambulance drive away, I’d thought fleetingly of following it on foot. But I’d ultimately rejected the idea. Even though I could travel instantly through space and time in my nightmares, I hadn’t discovered a way to do so while awake. I still moved at a normal human pace, and I could probably walk for years before I found the hospital where the ambulance had taken the boy.

It hadn’t occurred to me until after the last car had left the riverbank that I could’ve snuck into an empty backseat, maybe gone with the driver to the hospital … and then what? The idea of stowing away with a living stranger on the slim possibility that I would end up at a hospital, wandering lost through its corridors in search of another stranger—well, I felt silly and irrational just imagining it.

Of course, milling around the scene of my death didn’t seem very rational, either.

From the bank of the river, I’d watched as police barricaded the gap in the bridge above me. I’d looked on as a wrecking crew, completely oblivious to their audience of one, towed the boy’s sodden car from the water. While these activities took place, I hardly questioned my desire to stay here—really, who wouldn’t be interested in such things?

But after the activity had ended, each subsequent moment I’d spent at this site made me feel more and more foolish.

For a while I’d tried to justify my need to linger. I told myself that I just needed some time to reorganize my thoughts before I began wandering aimlessly again.

Deep down, however, I knew the truth. I knew the real reason I didn’t leave this river.

I didn’t want to wander aimlessly anymore. I wanted to wander with a very specific aim. I wanted to wander to someone.

Someone who had nearly died (or actually died; I couldn’t be sure) in this river. Someone who, in doing so, had changed me irrevocably.

There were signs, other than my unwillingness to leave, that a change had taken place. First, there were what I came to think of as “flashes.” I would be walking through the woods beside the river, or along the bank, and a flash would happen. An image—bright and colorful, and full of smell and taste—would flash across my mind and then disappear as fast as it had arrived.

Like my nightmares, the flashes occurred unexpectedly. But instead of terror and pain, the flashes brought something infinitely more appealing: what I could only assume were memories of my life before death.

Nothing significant had appeared yet: a black ribbon fluttering in the wind; the sound of a tire squealing on pavement; the earthy smell of a spring storm. No people, no names, no fleshed-out scenes to give me some clue as to who I was or why I’d died. Nor did I really experience the tastes and smells. The things that occurred in the flashes were more like ghosts of those sensations. But they were enough.

Читать дальше