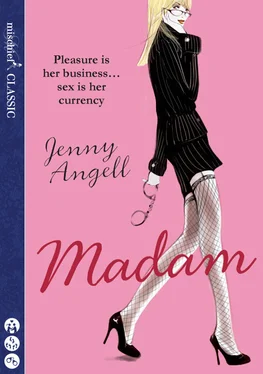

And most importantly, I learned that I could do it better than her.

So I took my almost-working car and my revived bank account, rented an apartment in Boston’s trendy Bay Village, and opened up my own business. That was nineteen years ago. I’ve been doing it ever since.

* * * * * *

I chose the name Peach from a short story.

It’s as good a source as any for finding a name, I suppose. But it also is weird, in a Twilight Zone kind of way, because the person who wrote that story later came to work for me for a couple of years. What are the chances of that happening? They must be a million to one.

What I didn’t want, above all, was to use my own name. I didn’t want the guys asking for Abby, or knowing anything about Abby. From the very beginning, I wanted an element of deniability to it all. I wanted to both be and not be this new persona.

So I became Peach.

I knew I had to keep my working life and my personal life very, very separate. To my friends and family, I would be Abby. To my girls and my clients, I’d be Peach. And that’s worked pretty well for me.

Which is not to say that I latched onto it right away. If I can sit here and talk calmly about having a family, having a business, juggling them the way any working mother does, you need to know that it didn’t come to me naturally.

In fact, for a whole lot of years, I was much more Peach than I was Abby. Sometimes I think I got a little lost in being Peach … so that’s part of what this story is about. Getting lost.

And getting found.

The door opened slowly, too slowly. The faces were grave.

I was pressed up against the wall in the corridor, scarcely daring to breathe. There was a very expensive vase on the table next to me, from some Chinese dynasty that’s remembered in the Western world only for its porcelain. I had been told to never touch the vase.

The voices inside the room had gone on for far too long, a steady murmur, the murmur of death.

Now the door was opening, and they were all coming out. My mother, her face red and blotchy from crying. Dr. Copeland. Two of my father’s business associates.

Dr. Copeland saw me first and, ignoring the other people – which was very unlike a grown-up – came over and squatted in the hallway next to me. “Abby,” he said, gently, “how long have you been here?”

I stifled a sob. “Forever,” I said. I felt that if I said anything more than that, I’d start crying, and it had been made clear to me that I was not to cry.

He didn’t go away, as I expected him to. He put a hand on my shoulder, instead. “You’re going to need to be a brave girl, Abby.”

“Yes, sir, I know.”

He frowned, as though that was the wrong answer. “But you can be brave and feel sad at the same time,” he said.

I glanced at my mother. She was standing with the light from the window behind her, and all I could see was her thin elegant outline. Her arms were crossed.

I didn’t have to see her face; I already knew what the expression was.

I looked back into the doctor’s kindly eyes with a quick indrawn breath and a little bit of panic. “I’ll be brave,” I assured him. Maybe if I said what he wanted me to say, he’d go away and not say things that made me want to cry.

He didn’t go away.

Instead, he scrunched down and sat on the floor next to me. I clearly heard my mother’s disapproving intake of breath, and stiffened, but she didn’t say anything. “Abby,” said Dr. Copeland, “you know that your daddy is very sick.”

No one had ever called him Daddy before, except me. My mother always prefaced references to him with “Your father.” I nodded.

He nodded, too, as though we had just shared a very deep secret. “Abby, I’m afraid that he’s going to die.”

My heart thudded, and I thought suddenly that I might throw up. I shouldn’t, I knew that I shouldn’t, but I wondered how I could keep it from happening. What can you do? Swallow it all back? I didn’t say anything and swallowed hard, and the feeling receded. Dr. Copeland squeezed my shoulders. “We’re all going to miss your daddy,” he said, “but do you know what, Abby? I think that you’re going to miss him most of all.”

I didn’t know how to respond, so I didn’t say anything.

The doctor gave me one last firm pat on the back and stood up, with some difficulty. One of my father’s business associates gave him a hand. My mother never moved.

Their voices faded away down the hallway and the big sweeping staircase that led downstairs. I stayed where I was, looking longingly at the closed door.

“Abby!” my mother called, her voice sharp. “Come downstairs now!”

I suppose that I went. I was good that way. Obedient.

I never saw my daddy again.

When I left Laura’s place, I had only the faintest idea how to make things work.

What I mean is, I knew what I didn’t want. In retrospect, maybe that’s a pretty good place to start.

I didn’t want to run an in-call service. That was the first decision. For a whole lot of reasons, I didn’t want in-call.

First of all, there was the risk associated with it. There’s always more risk when you have an actual physical place where something illegal is going on. But there was the intrusion, as well, the sense of never quite knowing where work ends and Real Life begins. Laura’s house was – well, Laura’s house. For Laura, my one and only role model in the business, there had never been a clear line between the two. If I didn’t make a distinction, it’s because she never did: her work was her life. I wanted my own space. I wanted my own life.

You have to understand something about this woman: this is someone who made arrangements for her son to get laid when he was fifteen. She sent one of her girls to him in his own bedroom, which was, incidentally, just up the stairs from where the girls all worked. Now that’s one hell of a birthday present from your mother.

I remember one Christmas party – Laura always threw these incredibly extravagant parties – watching her son dancing with the girls with a champagne glass in his hand and an erection in his pants. The girls took off more and more of their clothes as the evening wore on, and Chris was there, right in the middle of it all. He was loving it, of course, but I couldn’t help thinking that his time would have been better spent making out in the back seat of a car somewhere.

There was something about the way Laura dealt with Chris that seemed wrong, really wrong, to me. I realize that many people – maybe even most people – think that sex workers have no ethics, no morals, no code of conduct. Well, I do. I may differ with other people on the definition of that code, but I have one all the same.

Not that I ever had much in common with Laura: we’re both madams; and that is pretty much where the resemblance ends.

She was prissy about cleanliness, as I mentioned, to the point of covering all her furniture in plastic, just like they used to do in the 1950s. (“Well,” she said to me once, as though it were the most logical thing in the world, “you never know who’s going to sit there, or what they’re going to do.” Yuck. I don’t ever want to not know what people are doing on my living room sofa). And yet this prissy housekeeper regularly freebased, leaving all sorts of paraphernalia around in her kitchen – aluminum foil, cigarette ashes, little gram bags of coke.

She was organized beyond belief, keeping this small notebook, adding up, who owed what to whom every night. Yet she couldn’t be bothered with all the work that went into brewing coffee and always drank hers instant.

Laura was, suffice it to say, a study in contrasts.

Читать дальше