“It doesn’t sound—” I began.

“I look to the future, never the past,” my father said. A fitting maxim, I thought, for the captain of a vehicle without a rear window.

Growing up, I’d heard almost nothing about the paternal side of my family. My father rarely spoke of his parents, and never to them. I learned my paternal grandfather’s first name in 1967, when a letter arrived from Tel Aviv, informing us of his death. My mother recalled aerogrammes with an Israeli postmark arriving in the early years of their marriage, addressed to István. They were from my father’s mother. My mother couldn’t read them—they were in Hungarian—and my father wouldn’t. My mother wrote back a few times in English, bland little notes about life as an American housewife: “Between taking care of Susan, cooking, and housekeeping, I’m very busy at home … Steven works a lot, plus many evenings doing ‘overtime.’” An excuse for his silence? By the early ’60s, the aerogrammes had stopped.

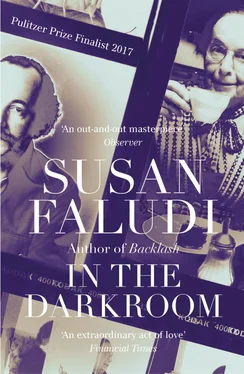

I knew a few fundamentals. I knew my father’s birth name: István Friedman, or rather, Friedman István; Hungarians put the surname first. He’d adopted Faludi after World War II (“a good authentic Hungarian name,” my father had explained to me), then Steven—or Steve, as he preferred—after he’d moved to the United States in 1953. I knew he was born and raised Jewish in Budapest. I knew he was a teenager during the Nazi occupation. But in all the years we lived under the same roof, and no matter how many times I asked and wheedled and sometimes pleaded for details, he spoke of only a few instances from wartime Hungary. They were more snapshots than stories, visual shrapnel that rattled around in my childish imagination, devoid of narrative.

In one, it is winter and dead bodies litter the street. My father sees the frozen carcass of a horse in a gutter and hacks off pieces to eat. In another, my father is on a boulevard in Pest when a man in uniform orders him into the Grand Hotel Royal. Jews are being shot in the basement. My father survives by hiding in the stairwell. In the third, my father “saves” his parents. How? I’d ask, hungry for details, for once inviting a filibuster. Shrug. “Waaall. I had an armband.” And? “And … I saaaved them.”

As the camper climbed the switchbacks, I gazed out at the terra-cotta rooftops of the hidden estates, trying to divine the outlines of my father’s youth. As a child and until the war broke out, he’d spent every summer in these hills. The Friedmans’ primary address was on the other side of the Danube, in a capacious flat in one of the two large residential buildings my grandfather owned in fashionable districts of Pest. My father referred to the family quarters at Ráday utca 9 as “the royal apartment.” But every May of my father’s childhood, the Friedmans would decamp, along with their maid and cook, to my grandfather’s other property in the hills, the family villa. There, an only child called Pista—diminutive for István—would play on the sloping lawn with its orchards and outbuildings (including a cottage for the resident gardener), paddle in the sunken swimming pool, and, the year he contracted rheumatic fever, lie on a chaise longue in the sun, tended by a retinue of hired help. As we ascended into the hills of Buda I thought, here I am in the city that was the forge of my father’s youth, the anvil on which his character was struck. Now it was the stage set of her prodigal return. This proximity gave me a strange sensation. All my life I’d had the man without the context. Now I had the context, but with a hitch. The man was gone.

3

The Original from the Copy

I’d met the lions on the Chain Bridge before, when I was eleven. We were on a family vacation in the summer of 1970: my mother, my father, my three-year-old brother, and me. It was, all and all, a vexed journey. One evening we drove across the river to attend an outdoor performance of Aida. I remember the crossing for its rare good cheer; family trips were always fraught affairs. The car seemed to float over the Danube, the cable lights winking at us from above, the leonine sentries heralding our arrival to the city. My father reminisced about how his nurse used to push his pram past the lions and over the bridge to the base of the Sikló, a charming apple-red funicular that chugged up the Castle Hill palisade. He told us the story about the sculptor who had forgotten to carve tongues for the lions: a child had pointed out their absence at the opening ceremonies, and the humiliated artist leaped off the bridge into the Danube. It was a popular tale in Hungary, he’d said, but “probably not true.”

Castle Hill, my father informed us, was honeycombed with subterranean caverns, carved out of the limestone millennia ago by thermal springs coming up “from the deep.” The occupying Turks had turned them into a giant labyrinth. “They say Vlad the Impaler—the real-life Dracula!—was locked up down there.” During World War II, the caves were retrofitted to accommodate air raid shelters and a military hospital. Thousands of the city’s inhabitants took refuge here for the fifty days of the Siege of Budapest. “It’s said that some people even had their mail delivered here,” my father reported. “But that’s probably a made-up story, too.”

Some days earlier, we had driven to Lake Balaton, south of Budapest. I remember walking a long way out into the shallow lake, the water only reaching my thighs. No matter how far I fled from shore, I could still hear my parents, their voices raised in acrid argument. The sour climate extended beyond our domestic circle. A scrim of sullenness seemed to hang over every encounter: the long waits in queues to receive a stamp so that we could proceed to other long queues to be issued other certifications of approval from scowling apparatchiks; the pitiful settee spitting yellowed foam in the guest room my father had rented; our aged landlady’s resentful eyes, sunk deep in a walnut-gnarled face, as she gave us each morning a serving of boiled raw milk, a thick curdled rind floating on its surface; the murky intentions of the “priest” in vestments who approached us one day after we’d toured the Benedictine monastery of Pannonhalma, asking my father if he’d deliver a letter to “friends” in the States—a government agent, my father said. The day we crossed the border into Hungary from Austria, customs officers combed through every inch of our luggage. My father stood to the side, uncomplaining, eager to please, a strange servility in his voice.

Throughout that visit, my father was in search of “authentic” Magyar folk culture. Driving through the countryside, we stopped to watch “traditional village dances” that were, in fact, staged tourist attractions: the government paid locals to whirl in what was billed as the national dress, the women in ornamental aprons and floral wreaths, the men in black vests and high leather boots. (As I’d learn later, the outfits and dances were only marginally traditional: they had been enshrined by urban nationalists in the mid-nineteenth century, and again in the interwar years, to create the impression of an ancient Magyar heritage.) In a village shop, my father insisted I try on folk dresses. As I modeled elaborately embroidered frocks, while cradling an elaborately clad Hungarian doll in my arms, my father took what felt like far too many rolls of film. The shop owner played stylist. Eventually my father purchased a lace-up bodice-and-dirndl number with a puffy-sleeved embroidered chemise, bell-shaped blue skirt, and a starched white apron with a tulip and rosebud motif. He thought I could wear it to school. His American daughter thought there was no way in hell she was going to junior high dressed as the Hungarian Heidi.

Читать дальше