From his domain in the basement, my father designed the stage sets he desired for his family. There was the sewing-machine table with a retractable top he built for my mother (who didn’t like to sew). There was the to-scale train set that filled most of a room (its Nordic landscape elaborately detailed with half-timbered cottages, shops, churches, inns, and villagers toting groceries and hanging laundry on a filament clothesline) and the fully accessorized Mobil filling station (hand-painted Pegasus sign, auto repair lift, working garage doors, tiny Coke machine). His two children played with them with caution; a broken part could be grounds for a tirade. And then there was one of my father’s more extravagant creations, a marionette theater—a triptych construction with red curtains that opened and closed with pulleys and ropes, two built-in marquees to announce the latest production, and a backstage elevated bridge upon which the puppeteer paced the boards and pulled the strings, unseen. This was for me. My father and I painted the storybook backdrops on large sheets of canvas. He chose the scenes: a dark forest, a cottage in a clearing surrounded by a crumbling stone wall, the shadowy interior of a bedroom. And he chose the cast (wooden Pelham marionettes from FAO Schwarz): Hunter, Wolf, Grandmother, Little Red Riding Hood. I put on shows for my brother and, for a penny a ticket, neighborhood children. If my father ever attended a performance, I don’t remember it.

“Visiting family?” my seatmate asked. We were in an airplane crossing the Alps. He was a florid midwestern retiree on his way with his wife to a cruise on the Danube. My assent prompted the inevitable follow-up. While I deliberated how to answer, I studied the overhead monitor, where the Malév Air entertainment system was playing animated shorts for the brief second leg of the flight, from Frankfurt to Budapest. Bugs Bunny sashayed across the screen in a bikini and heels, befuddling a slack-jawed Elmer Fudd.

“A relative,” I said. With a pronoun to be determined, I thought.

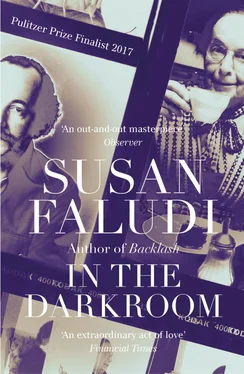

In September 2004, I boarded a plane to Hungary. It was my first visit since my father had moved there a decade and a half earlier. After the fall of Communism in 1989, Steven Faludi had declared his repatriation and returned to the country of his birth, abandoning the life he had built in the United States since the mid-’50s.

“How nice,” the retiree in 16B said after a while. “How nice to know someone in the country.”

Know? The person I was going to see was a phantom out of a remote past. I was largely ignorant of the life my father had led since my parents’ divorce in 1977, when he’d moved to a loft in Manhattan that doubled as his commercial photo studio. In the subsequent two and a half decades, I’d seen him only occasionally, once at a graduation, again at a family wedding, and once when my father was passing through the West Coast, where I was living at the time. The encounters were brief, and in each instance he was behind a viewfinder, a camera affixed to his eye. A frustrated filmmaker who had spent most of his professional life working in darkrooms, my father was intent on capturing what he called “family pictures,” of the family he no longer had. When my boyfriend had asked him to put the camcorder down while we were eating dinner, my father blew up, then retreated into smoldering silence. It seemed to me that was how he’d always been, a simultaneously inscrutable and volatile presence, a black box and a detonator, distant and intrusive by turns.

Could his psychological tempests have been protests against a miscast existence, a life led severely out of alignment with her inner being, with the very fundaments of her identity? “This could be a breakthrough,” a friend suggested, a few weeks before I boarded the plane. “Finally you get to see the real Steven.” Whatever that meant: I’d never been clear what it meant to have an “identity,” real or otherwise.

In Malév’s economy cabin, the TV monitors had moved on to a Looney Tunes twist on Little Red Riding Hood. The wolf had disguised himself as the Good Fairy, in pink tutu, toe shoes, and chiffon wings. Suspended from a wire hanging off a treetop, he flapped his angel wings and pretended to fly, luring Red Riding Hood out on a limb to take a closer look. Her branch began to crack, and then the entire top half of the tree came crashing down, hurtling the wolf in drag into a heap of chiffon on the ground. I watched with a nameless unease. Was I afraid of how changed I’d find my father? Or of the possibility that she wouldn’t have changed at all, that he would still be there, skulking beneath the dress.

Grandmother, what big arms you have! All the better to hug you with, my dear.

Grandmother, what big ears you have! All the better to hear you with, my dear.

Grandmother, what big teeth you have! All the better to eat you with, my dear!

And the Wicked Wolf ate Little Red Riding Hood all up …

Malév Air #521 landed right on time at Budapest Ferihegy International Airport. As I dawdled by the baggage carousel, listening to the impenetrable language (my father had never spoken Hungarian at home, and I had never learned it), I considered whether my father’s recent life represented a return or a departure. He had come back here, after more than four decades, to his birthplace—only to have an irreversible surgery that denied a basic fact of that birth. In the first instance, he seemed to be heeding the call of an old identity that, no matter how hard he’d run, he’d failed to leave behind. In the second, she’d devised a new one, of her own choice or discovery.

I rolled my suitcase through the nothing-to-declare exit and toward the arrivals hall where “a relative,” of uncertain relation to me, and maybe to herself, was waiting.

In my luggage were a tape recorder, a jumbo pack of AA batteries, two dozen microcassettes, a stack of reporter’s notebooks, and a single-spaced ten-page list of questions. I had begun the list the day I’d received the “Changes” e-mail with its picture gallery of Stefánie. If my photographer father favored the image, her journalist daughter preferred the word. I’d typed up my questions and, after much stalling, picked up the phone. I had to look up my father’s number in an old address book .

A taped voice said, in Hungarian and then in English, “You have reached the answering machine of Steven Faludi …” By then, more than a month had passed since she’d returned from Thailand. I added another to my list of questions: Why haven’t you changed your greeting? I left a message, asking her to call. I sat by a silent phone all that day and evening.

That night, in a dream, I found myself in a dark house with narrow, crooked corridors. I walked into the kitchen. Crouched against the side of the oven was my father, very much a man. He looked frightened. “Don’t tell your mother,” he said. I saw he was missing an arm. The phone rang. Jolted awake, I lay in bed, ignoring the summons. It was half past five in the morning. An hour later, I forced down a cup of coffee and returned the call. It wasn’t just the early hour that had stayed my hand. I didn’t want to answer the bedside extension. My list of questions was down the hall in my office.

“Haaallo?” my father said, with the protracted enunciation I’d heard so infrequently in recent years, that Magyar cadence that seemed to border on camp. Hallo. As my father liked to note, the telephone salutation was the coinage of Thomas Edison’s assistant, Tivadar Puskás, the inventor of the phone exchange, who, as it happened, was Hungarian. “ Hallom !” Puskás had shouted when he first picked up the receiver in 1877, Magyar for “I hear you!” Would she?

Читать дальше