How the United States was Shaped by the Greatest Land Sale in History

ANDRO LINKLATER

COVER

TITLE PAGE MEASURING AMERICA How the United States was Shaped by the Greatest Land Sale in History ANDRO LINKLATER

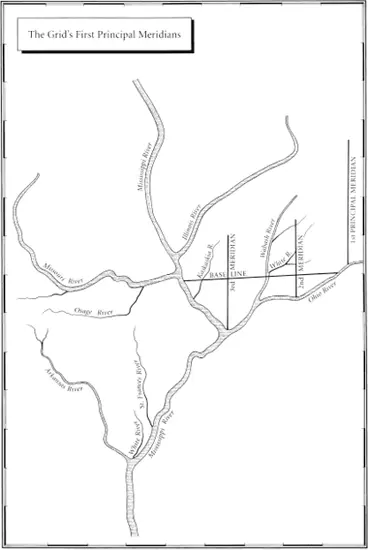

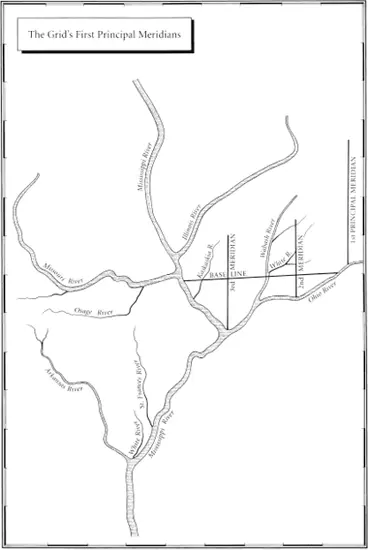

MAPS MAPS

INTRODUCTION

1 The Invention of Property

2 Precise Confusion

3 A Hunger for Land

4 Life, Liberty and What?

5 Simple Arithmetic

6 A Line in the Wilderness

7 The French Dimension

8 Democratic Decimals

9 Annie’s Ounce

10 The Birth of the Metric System

11 Dombey’s Luck

12 The End of Rufus

13 The Immaculate Grid

14 The Shape of Cities

15 Hassler’s Passion

16 The Dispossessed

17 The Limit of Enclosure

18 Four Against Ten

19 Metric Triumphant

EPILOGUE: The Witness Tree

BIBLIOGRAPHY

INDEX

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ALSO BY THE AUTHOR

COPYRIGHT

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

In every country with an industrial history there are towns like East Liverpool, Ohio. They were built close to the coalfields that provided their energy and on the banks of large rivers that carried away their heavy products. On the Clyde in Scotland, the Tees in England, the Ruhr in Germany, mighty structures of iron and steel were smelted, beaten and annealed to make the skeleton for the first modern society, and the towns grew rich and confident in a grey haze of fumes and steam and effluent. Today their colours are rusty metal and faded red brick, the air is clear, the atmosphere uncertain, and in the shabby streets regeneration is pitted against boredom and drugs.

Clay was the material that made East Liverpool wealthy, Pennsylvania coal fuelled the furnaces, and the Ohio river carried away enough plates and cups to let the inhabitants boast that the town was ‘the pottery capital of the world’. Where once dozens of factories and chemical works lined the banks, the only reminder now of East Liverpool’s industrial past is a solitary chimney stack pumping heavy coils of smoke into the sky. The barges still come up the Ohio river carrying minerals and fertilisers, but mostly for use across the river in the nearby Pittsburgh area. They unload at depots like that belonging to the S.H. Bell Company, whose functional warehouses and concrete docks annually handle thousands of tons of steel and copper at the upriver end of town.

The place could hardly be more anonymous. Above the Bell Company’s dock, Pennsylvania Route 68 invisibly changes to Ohio Route 38, and trees half-hide some signs by the roadside. Even someone familiar with the historical significance of this particular spot, who has travelled several thousand miles to find it, and whose eyes are flickering wildly from the narrow blacktop to the nondescript verge between road and river, can drive a couple of hundred yards past it before hitting the brakes.

The language of the signs is equally undemonstrative. A stone marker carries a plaque headed ‘The Point of Beginning’ which reads, ‘1112 feet south of this spot was the point of beginning for surveying the public lands of the United States. There on September 30 1785, Thomas Hutchins, first Geographer of the United States, began the Geographer’s Line of the Seven Ranges.’

There is nothing else to suggest that it was here that the United States began to take physical shape, nothing to indicate that from here a grid was laid out across the land that would stretch west to the Pacific Ocean, and north to Canada, and south to the Mexican border, and would cover over three million square miles, and would create a structure of land ownership unique in history, and would provide the invisible web that supported the legend of the frontier with its covered wagons and cowboys, and its farmers and goldminers, and would insidiously permeate its formation into the unconscious mind of every American who ever owned a square yard of soil.

It is hilly country, covered in the same oak, dogwood and hickory that Hutchins saw, and in the bright light of a September afternoon it rises high above the broad river in crimson and copper waves. ‘For the distance of 46 chains and 86 links West,’ Hutchins wrote in his first description of the territory, ‘the Land is remarkably rich with a deep, black Mould, free from Stone.’ He was Robinson Crusoe, landed in an uncharted wilderness, and his purpose was something close to magic – to measure it and map it and turn it into property. It had been lived in by the Delaware and passed through by the Miami and occupied by the Iroquois, but no one had ever owned it. No one had ever thought of owning it. The idea of one person owning land did not yet exist on the west bank of the Ohio.

The wand that would make this magic possible was there in the first sentence of Hutchins’ report. The land would be measured in chains and links. In most circumstances, a chain imprisons; here it released. What it released from the billowing, uncharted land was a single element – a distance of twenty-two yards. That was the length of the chain. Repeated often enough, added, squared and multiplied, the measurement gave a value to the land that could be computed in money terms.

What began here on the banks of the Ohio river was not just a survey. The real significance of the spot now covered by the Bell Company’s concrete dock is that this was where the most potent idea in economic history – that land might be owned, like a horse or a house – was first released into the western wilderness and encouraged to spread across the land mass of the United States. But in his poem ‘The Gift Outright’, Robert Frost caught at a thought more powerful yet. The earth has its own magic, and those who seek to possess it run the risk of being possessed by it. It was the desire to own this particular land, Frost mused, that made its owners American.

These were the great forces that Captain Thomas Hutchins, Geographer to the United States, set in motion when he first unrolled the loops of his chain at the Point of the Beginning.

ONE The Invention of Property

THE IMPOSING LIBRARY of the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors in London is strategically situated. In one direction its tall windows look over the street to Whitehall, where the Tudor and Stuart sovereigns ruled in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and in another they gaze across Parliament Square towards the House of Commons, power-base of the rising class of landed gentry who during those two centuries challenged the royal authority. It is just possible to imagine the atmosphere of righteous indignation and pervading apprehension which accompanied the struggle between the two, but in the small, 450-year-old, leather-bound books kept in the Institution’s library, the reality that gave rise to the battles remains vividly alive.

In the earliest, such as Master Fitzherbert’s The Art of Husbandry , published in 1523, a surveyor still fills his original, feudal role as the executive officer of a landed nobleman. His duty is simply to oversee (the word ‘surveyor’ is derived from the French sur = over and voir = see) the estate. He is to walk over the land, noting the ‘buttes and bounds’ of the tenants’ holdings, and then to assist in drawing up the official record or court roll of what duties they owed. A model report, Fitzherbert suggests, might run like this: the land of a particular tenant ‘lyeth between the mill on the north side, and the South Field on the south, butteth upon the highway, and conteyneth xii [twelve] perches [a perch, like a rod, equals 16½ feet] and x [ten] fote [feet] in bredthe by the hyway, and ix [nine] perches in length, and payeth … two hennes at Christmas and two capons at Easter’.

Читать дальше