There were also continuing disputes raging within the science—between the plutonists and the neptunists, for example, or between the catastrophists and the calmer-minded supporters of uniformitarianism. And the aristocrats who had claimed the science for themselves—rich men who amassed gaudy collections of minerals and fossils to decorate the drawing rooms of their mansions—were also at the time beginning to yield to a wider public sense of inquiry, with every farmer and walker and settler keeping an eye on the land, curious to know what it was made of and why.

But for some, the academic din in Europe proved perhaps just a little too much. William Maclure soon came back to America, admitting to being overwhelmed by the topographic complexity of the European landscape. He decided he would instead be more suitably self-employed discovering the geology of his newly adopted homeland. He would find out what America was made of, he decided. And he would draw a map of it.

DRAWING THE COLORS OF ROCKS

This was in 1799. For the next ten years, Maclure tramped and stagecoached relentlessly up and down and across the narrow swath of territory that lay between the Appalachians and the Atlantic—the country’s most known and settled region. He wandered on the far side of the Alleghenies, too, through what is now Arkansas and Mississippi, though it is not certain if he managed to get as far north as the sparsely settled territories of Ohio and Indiana. He managed to get himself all the way down to Georgia. We cannot be certain that he got all the way up to Maine, but he did claim to have crossed the hills and valleys of the Appalachians at least twenty-two times—which, given the condition of the roads at the time, was no mean achievement.

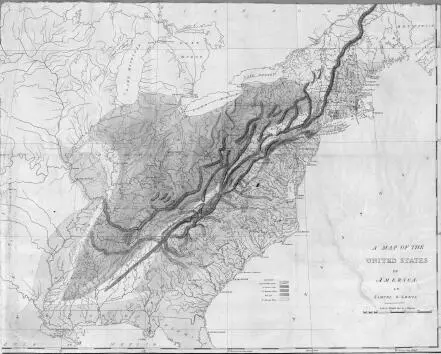

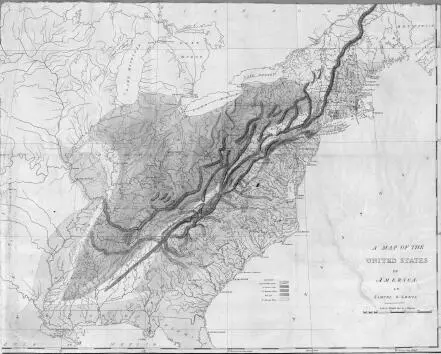

But however he did it, wherever he happened to go, however many miles he walked, rode, or went in greater comfort by carriage and diligence and cart, he achieved something truly memorable, with a significance that went beyond what might have seemed its purely American relevance. He announced it in an address before an evening meeting of the American Philosophical Society in 1809 after offering his first thoughts on the geology of the nation. Crucially, he included with his seventeen pages of explanation a hand-colored map—the first geological map in the world, some say, and certainly the first recognizable geological map of the United States.

It is a document of curious beauty, even though its simple innocence rendered it of little real use. It is based on a topographic map engraved by Samuel Lewis, a Philadelphia mapmaker who was at the time perhaps the country’s preeminent cartographer. 1Maclure used vivid watercolors—yellow, red, blue, pink, and green—to paint onto the base map’s eastern half the five main divisions, as early geology was inclined to see them, of America’s rocks.

The swaths of color he used—to show different kinds of rock, not different ages, as maps do today—all trend across the states from the southwest up to the northeast. They sweep along in approximate parallel to the lines of the Appalachian hills—which on the map sheet are picked out in caterpillarlike lines of ugly fuzziness; that was the device Lewis had employed to depict chains of mountains on all of his maps.

The results of Maclure’s estimated fifty survey journeys across the Appalachians led to the publication in 1809 of this crude but memorable first geological map of the then United States. It predated by six years the much more famous British map by William Smith.

Four basic types of rock make up the geology of America, as it was described in 1809. On the western side of the mountains, everything on Maclure’s map is colored pale blue, indicating the presence of so-called secondary rocks, fossil-bearing sediments, by and large. On the eastern side, the ocean side, all is by contrast hand-colored yellow, indicating alluvial rocks, gravels and sands and fresh-from-the-ocean clays.

The summits of the Appalachian mountain ranges Maclure showed to be quite geologically different and painted them in vivid streaks of deep blue and deep red denoting what early geological theorists called transition rocks. He also noted the presence of hard granitic outcrops of what he called primitive rocks; these he colored in pink. And for good measure, he also invented a fifth category for deposits of rock salt.

As art, Maclure’s maps—he made a revised version in 1818—are undeniably pretty; but as science, they were confusing and, in truth, pretty useless. Had they been Maclure’s sole achievement, he might then have slipped into obscurity. But that was not to be.

THE WELLSPRING OF KNOWLEDGE

Maclure’s eagerness to instill in American working-class youth a love for the practical—for the skills of farming; for a knowledge of geography; for the learning of natural history, statistics, biology—remained for years little more than an unrealized dream. But all changed in 1824, when he traveled to Scotland and had his first meeting with Robert Owen. That was when he was first seized with the idea of joining a utopian commune, transforming himself from a mapmaker into a missionary, and becoming America’s first geological messiah.

Owen was a Welshman who had made his fortune from the spinning of cotton in Scotland. He had carefully created in New Lanark a showpiece of social engineering for his mill workers—a near-ideal industrial environment, as he saw it, a community that was clean, healthy, well paid, disciplined, and morally sound, its children better educated than those in the finest paid schools in the land. So successful and admired had been New Lanark that Owen decided to expand. In the winter of 1824, he took his millennial dreams and blueprints for popular communal perfection across to America and started the process without delay by buying all of the land and real estate that the departing German settlers had created for themselves in New Harmony.

He reasoned that two thousand or so people could live together around an immense quadrangle he would build in the town. They would govern themselves, farm the land collectively and intelligently, live congenially without money, commune among themselves in the gardens within the buildings, and discipline themselves to hard work and moderate celibacy. His ideals were to all intents and purposes the ideals of the early Soviets, with communities to be run according to the familiar Marxist precept of fifty years later: “From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs.”

After settling his purchase of New Harmony, he came back east on a whirlwind recruiting mission. The fame he had won from his Scottish experiment preceded him, and as a successful industrialist, he found immediate and ready acceptance everywhere. At least, he did at first. He was able to meet without difficulty all of the privileged and the progressive figures of the Philadelphia Main Line, as well as chiefs of two Indian tribes. He won an audience with President Monroe, took tea with Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, and gave two public lectures in the Capitol. John Quincy Adams, the president-elect, came to both talks, and was so taken that he had Owen build a scale model of his proposed New Harmony building and display it at the White House.

It was while he was in Pennsylvania that Owen achieved his greatest coup, the one whose effects would linger longest, in managing to persuade William Maclure to come on board.

At the time, Maclure, his mapmaking success well in his past, had won fresh fame as a campaigning education reformer; and as president of the American Academy of Natural Sciences, he was seen not just as one of the preeminent scientists of his time, but as a great educational theorist, too. At their first meeting, Owen lost no time in reminding Maclure of his own, rather similar credentials. He assured him that what Maclure had seen of his success back in Scotland just a matter of months earlier could and should now be re-created in America.

Читать дальше