But one thing we did have was … a television. The presence of this television refocused the whole of my early existence. Through the lens of the TV screen – seven or eight inches across, black and white and grainy – came the wide world. Valve-driven, it took minutes to warm up, and there was a long, slow dying of the light to a singularity when it was switched off, which became a watchable event in its own right. We hosted visitors who came to look at it, caress it and not even watch it – it had such mystique. On the front were occult buttons and dials that turned like great combination locks to select the only two channels available.

The outside world, that is to say anywhere outside Worksop, was accessed primarily by gossip – or the Daily Mirror . The newspaper was always used to make the fire and I usually saw the news two days late, shortly before it was consigned to the inferno. When Yuri Gagarin became the first man to go into space I remember staring at the picture and thinking, How can we burn that? I folded it up and kept it.

If gossip or old newspaper wouldn’t do, the world outside might require a phone call. The big red phone box served as a cough, cold, flu, bubonic plague, ‘you name it you’ll catch it’ distribution centre for the neighbourhood. There was always a queue at peak hours, and a hellish combination of buttons to press and rotary dials in order to make a call, with large buckets of change required for long conversations.

It was like a very inconvenient version of Twitter, with words rationed by money and the vengeful stares of the other 20 people waiting in line to inhale the smoke-and-spit-infused mouthpiece and press the hair-oiled and sweat-coated Bakelite earpiece to the side of their head.

There were certain codes of conduct and regimes to obey in Worksop, although etiquette around the streets was very relaxed. There was little crime and virtually no traffic. Both my grandparents walked everywhere, or caught the bus. Walking five or ten miles each way across fields to go to work was just something they were brought up to do, and so I did it too.

The whole neighbourhood was in a permanent state of shift work. Upstairs curtains closed in daytime meant ‘Tiptoe past – coal miner asleep’. Front room curtains closed: ‘Hurry past – dead person laid out for inspection’. This ghoulish practice was quite popular, if my grandmother was to be believed. I would sit in our front room – permanently freezing, deathly quiet, bedecked with horse brasses and candlesticks that constantly required polishing – and imagine where the body might lie.

During the evening the atmosphere changed, and home turned into a living Gary Larson cartoon. Folding wooden chairs turned the place into a pop-up hair salon, with blue as the only colour and beehive the only game in town. Women with vast knees and polythene bags over their heads sat slowly evaporating under heat lamps as my grandmother roasted, curled and produced that awful smell of dank hair and industrial shampoo.

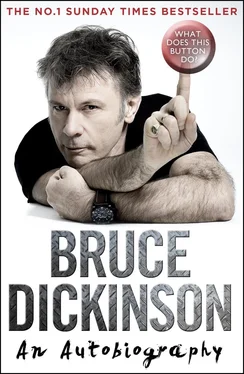

My escape committee was my uncle John. He forms quite an important part of what button to push next.

First of all, he wasn’t my uncle. He was my godfather – my grandfather’s best mate – and he was in the Royal Air Force and had fought in the war. As a bright working-class boy he was hoovered up by an expanding RAF, which required a whole host of technological skills that were in short supply, as one of Trenchard’s apprentices. An electrical engineer during the Siege of Malta, Flight Sergeant John Booker survived some of the most nail-biting bombardments of the war on an island Hitler was determined to crush at all costs.

I have his medals and a copy of his service Bible, annotated accordingly with verses to give support at a time when things must have been unimaginably grim. And there are pictures, one with him in full flying gear, about to stow away on a night-flying operation, which, as ground crew, was utterly unnecessary – done just for the hell of it.

While I sat on his knee he regaled me with aircraft stories and I touched his silvered Spitfire apprentice model, and a brass four-engined Liberator, with plexiglass propeller disc melted from a downed Spitfire and a green felt pad under its wooden plinth, the material cut from a shattered snooker table in a bombed-out Maltese club. He spoke of airships, of the history of engineering in Britain, of jet engines, Vulcan bombers, naval battles and test pilots. Inspired, I would sit for hours making model aircraft like many a boy of my generation, fiddling with transfers – later upgraded to decals, which sounded so much cleverer. It was a miracle any of my plastic pilots ever survived combat at all, given the fact that their entire bodies were encased in glue and their canopies covered in opaque fingerprints. The model shop in Worksop where I built my plastic air force was, amazingly, still there the last time I looked, on the occasion of my grandmother’s funeral.

Because Uncle John was a technical sort of chap, he had a self-built pond the size of the Möhne Dam, full of red goldfish and cunningly protected by chicken wire, and he drove a rather splendid Ford Consul, which was immaculate, of course. It was this car that transported me to my first airshow in the early sixties, when health and safety was for chickens and the term ‘noise abatement’ had not even entered the vocabulary.

Earthquaking jets like the Vulcan would shatter roofs performing vertical rolls with their giant delta wings while the English Electric Lightning, basically a supersonic firework with a man perched astride it, would streak past inverted, with the tail nearly scoring the runway. Powerful stuff.

Uncle John introduced me to the world of machinery and mechanisms, but I was equally as drawn to the steam trains that still plied their trade through Worksop station. The footbridge and the station today are virtually unchanged to those of my childhood. I swear that the same timbers I stood on as a boy still exist. The smoke, steam and ash clouds which enveloped me mingled with the tarry breath of bitumen to sting my nostrils. I walked to and from the station recently. I thought it was a bloody long way, but as a child it felt like nothing. The smell still lingers.

In short order, I would have settled for steam-train driver, then maybe fighter pilot … and if I got bored with that, astronaut was always a possibility, at least in my dreams. Nothing in childhood is ever wasted.

Somewhere, the fun has to stop, and so I went to school. Manton Primary was the local school for coalminers’ kids. Before it was closed, it achieved a level of notoriety with Daily Mail readers as the school where five-year-olds beat up the teachers. Well, I don’t recollect beating up any teachers, but I was given the gift of wings and also boxing lessons, after a fracas over who should play the role of Angel in the nativity play. I was lusting after those wings but instead got a good kicking in the melee that continued outside the school gates. The outcome was far from satisfactory. When I returned from school, dishevelled and clothes ripped, my grandfather sat me down and opened my hands, which were soft and pudgy. His hands were rough, like sandpaper, with bits of calloused skin stuck like coconut flakes to the deep lines that opened up as he spread his palms in front of me. I remember the glint in his eye.

‘Now, make a fist, lad,’ he said.

So I did.

‘Not like that – you’ll break your thumb. Like this.’

So he showed me.

‘Like this?’ I said.

‘Aye. Now hit my hand.’

Not exactly The Karate Kid – no standing on one leg on the end of a boat, no ‘wax on, wax off’ Hollywood moment. But after a week or so he took me to one side, and very gently, but with a steely determination in his voice, said, ‘Now go and find the lad that did it. And sort him out.’

Читать дальше