4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.4thEstate.co.uk

This eBook first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2017

First published in the United States by Ecco, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers , in 2017

Copyright © 2017 by Amy Tan

Cover illustration by Michelle Thompson. Images by kind permission of the author.

‘One of the Butterflies’ by W. S. Merwin taken from The Shadow of Sirius (Bloodaxe Books, 2008) and reproduced by permission of Bloodaxe Books.

www.bloodaxebooks.com

‘The Breaker of Combs’ was first published in Zyzzyva , October 2016.

‘The Unfurling of Leaves’ was first published in Allure magazine, November 2005, titled as ‘A Natural Woman.’

Amy Tan asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780007585571

Ebook Edition © November 2018 ISBN: 9780007585564

Version: 2018-09-25

For Daniel Halpern,

suddenly and finally,

our book.

[From the journal]

2012

You think you are oceans apart when it is really only a slipstream that you fell into by accident or inattention.

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Introduction – Where the Past Begins

PROLOGUE – The Breaker of Combs

I. IMAGINATION

CHAPTER ONE – A Leaky Imagination

CHAPTER TWO – Music as Muse

Quirk – Souvenir from a Dream

CHAPTER THREE – Hidden Genius

Interlude – Reorientation: Homer, Alaska

II. MEMORY IN EMOTION

CHAPTER FOUR – Genuine Emotions

CHAPTER FIVE – The Feeling of What It Felt Like When It Happened

Quirk – A Mere Mortal at Age Twenty-Five

Quirk – A Mere Mortal at Age Twenty-Six

Quirk – How to Change Fate: Step 1

III. RETRIEVING THE PAST

Interlude – The Unfurling of Leaves

Interlude – The Auntie of the Woman Who Lost Her Mind

CHAPTER SIX – Unstoppable

Quirk – Time and Distance: Age Twenty-Four

Quirk – Time and Distance: Age Fifty

Quirk – Time and Distance: Age Sixty

IV. UNKNOWN ENDINGS

CHAPTER SEVEN – The Darkest Moment of My Life

Quirk – Nipping Dog

CHAPTER EIGHT – The Father I Did Not Know

Quirk – Reliable Witness

V. READING AND WRITING

Interlude – I Am the Author of This Novel

CHAPTER NINE – How I Learned to Read

Quirk – Splayed Poem: The Road

Quirk – Eidolons

CHAPTER TEN – Letters to the Editor

CHAPTER ELEVEN – Letters in English

Quirk – Why Write?

VI. LANGUAGE

CHAPTER TWELVE – Language: A Love Story

Quirk – Intestinal Fortitude

CHAPTER THIRTEEN – Principles of Linguistics

Epilogue – Companions in the House

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Also by Amy Tan

About the Publisher

INTRODUCTION

WHERE THE PAST BEGINS

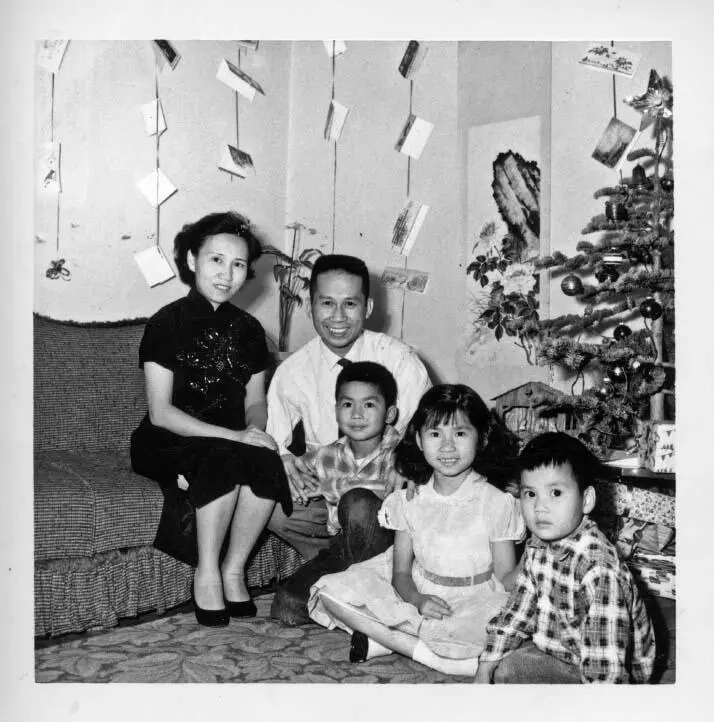

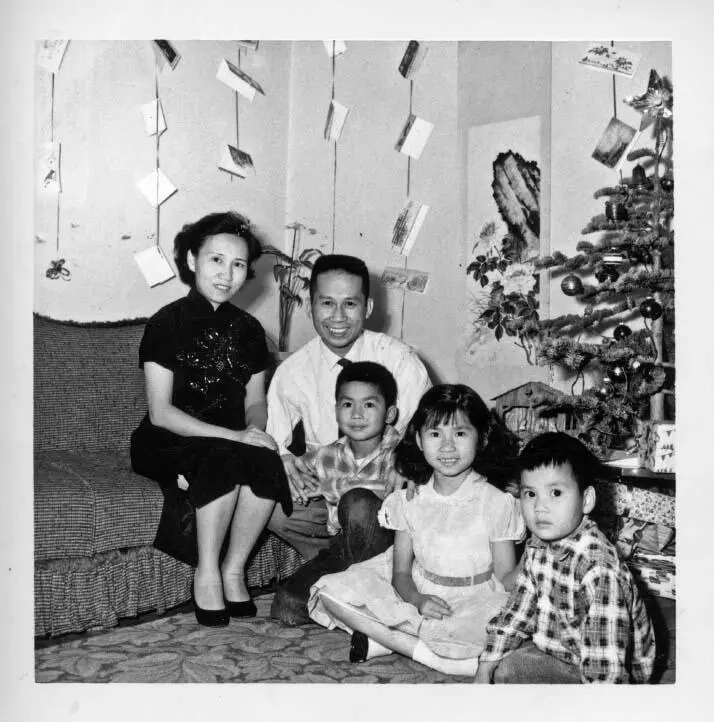

In my office is a time capsule: seven large clear plastic bins safeguarding frozen moments in time, a past that began before my birth. During the writing of this book, I delved into the contents—memorabilia, letters, photos, and the like—and what I found had the force of glaciers calving. They reconfigured memories of my mother and father.

Among the evidence were my parents’ student visas to the United States, letters from the U.S. Department of Justice regarding their deportation, as well as an application for citizenship. I found artifacts of life’s rites of passage: wedding announcements, followed soon by birth announcements, baby albums with tiny black handprints and downy locks of hair; yearly diaries; the annual Christmas letters with complaints and boasts about the children; floral-themed birthday and anniversary cards; a list of twenty-two people who had given floral contributions for my father’s funeral; and condolence cards bearing illustrations of crosses, olive trees, and dusk at the Garden of Gethsemane. There was also a draft of a surprising mature-sounding letter that I had written to serve as the template my mother could copy to thank people for their sympathy.

Perhaps the most moving discoveries were the letters to me from my mother and the letters to my mother from me. She had saved mine and I had saved hers, even the angry ones, which is proof of love’s resilience. In another box, I found artifacts of our family’s hard work: my mother’s ESL essay on becoming an immigrant and her nursing school homework; my father’s thesis, sermons, and his homework for a graduate class in electrical engineering; my grade school essays and my brother Peter’s history compositions; the report cards of Peter, John, and me, from kindergarten through high school, as well as my father’s college records. In different files, I recovered my father’s and mother’s death certificates. I haven’t come across Peter’s yet, but I found a photo of him in a casket, his sixty-pound body covered by a high school letterman jacket, but with nothing to conceal the mutilation of his head by surgeries and an autopsy. So now I have to ask myself: What kind of sentimentality drove me to keep that?

Actually, I never throw away photos, unless they are blurry. All of them, even the horrific ones, are an existential record of my life. Even the molecules of dust in the boxes are part and parcel of who I am—so goes the extreme rationale of a packrat, that and the certainty that treasure is buried in the debris. In my case, I don’t care for dust, but I did find much to treasure.

To be honest, I have discarded photos of people I would never want to be reminded of again, a number that, alas, has grown over the years to eleven or twelve. The longer I live the more blurry photos I’ve accumulated, along with a few sucker punches from people I once trusted and who did the equivalent of knocking me down to be first in line at the ice-cream truck. Age confers this simple wisdom: Don’t expose yourself to malarial mosquitoes. Don’t expose yourself to assholes. As it turns out, throwing away photos of assholes does not remove them from consciousness. Memory, in fact, gives you no choice over which moments you can erase, and it is annoyingly persistent in retaining the most painful ones. It is extraordinarily faithful in recording the most hideous details, and it will recall them for you in the future with moments that are even only vaguely similar.

Читать дальше