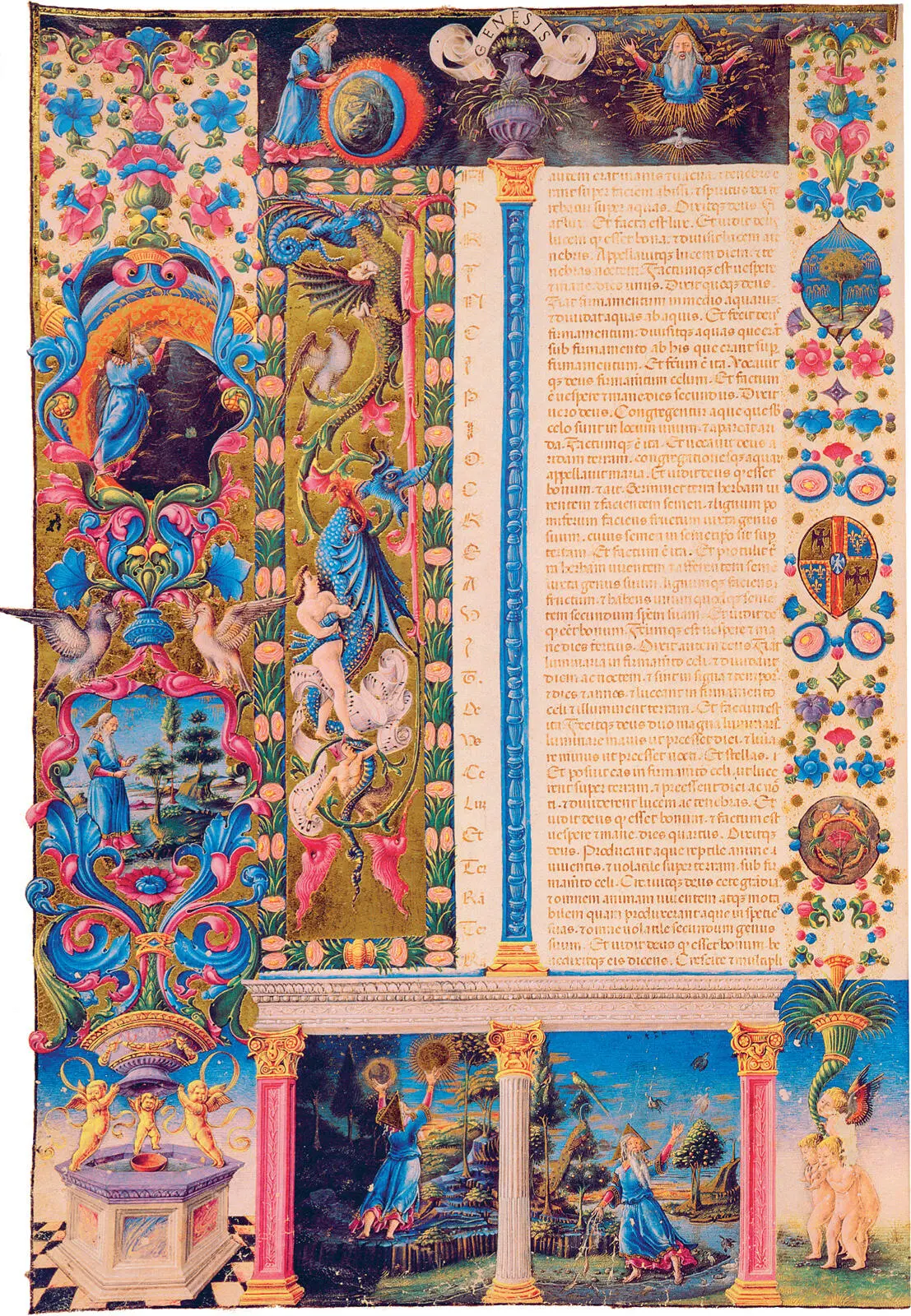

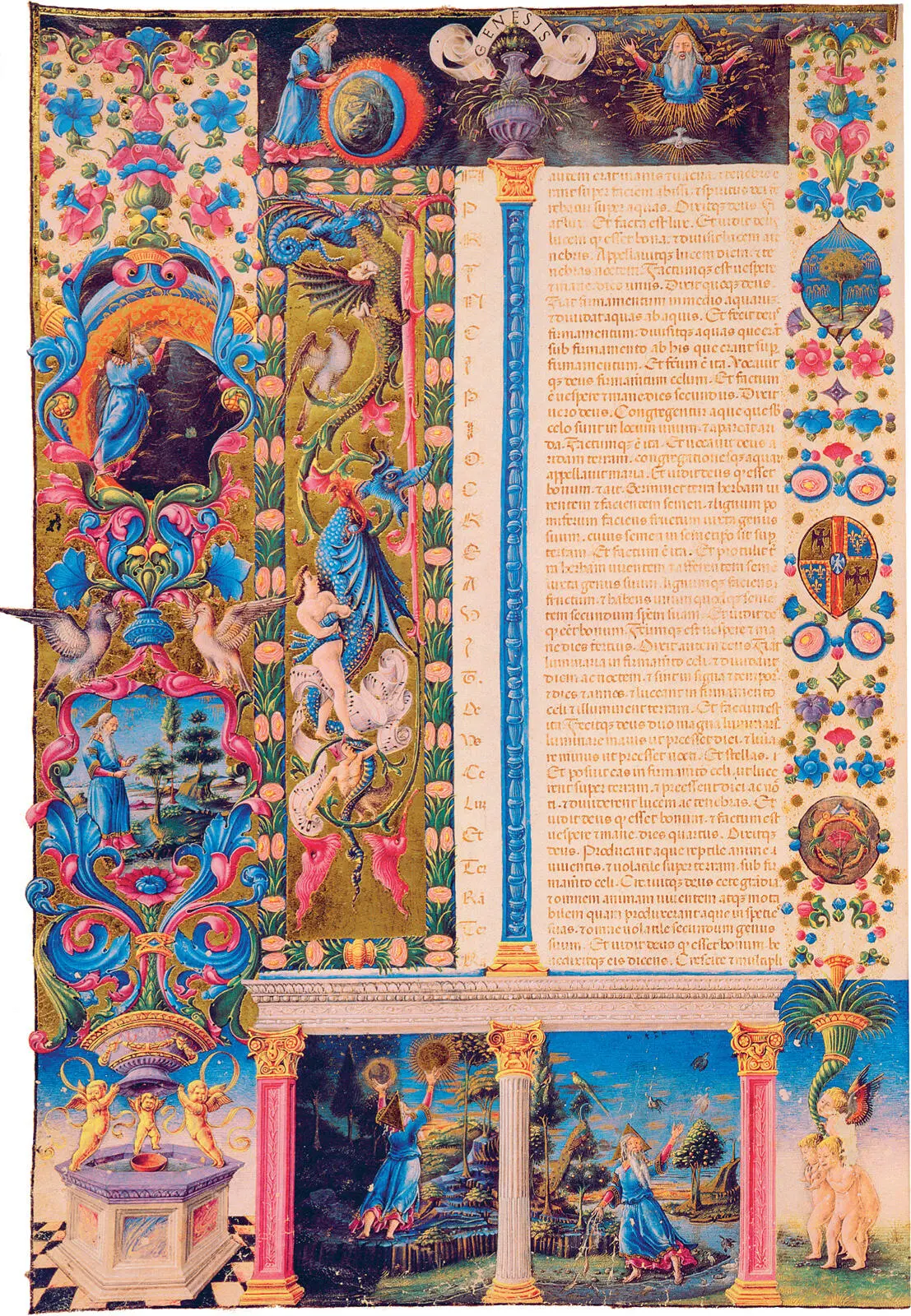

Bridgeman Art Library: Biblioteca Estense Universitaria, Modena, Italy

A piece of fine parchment paper showing Genesis, the creation of the universe, from the magnificent Italian Renaissance Bible of Borso d’Este Vol 1.

4

Fish baked in fig leaves

350 BC

AUTHOR: Archestratus, FROM: Hedypatheia (Life of Luxury)

You could not possibly spoil it even if you wanted to … Wrap it [the fish] in fig leaves with a little marjoram. No cheese, no nonsense! Just place it gently in fig leaves and tie them up with a string, then put it under hot ashes.

Archestratus’s mission in life was to visit as many lands as he could reach in search of good things to eat. A Sicilian, he ventured all over Greece, southern Italy, Asia Minor and areas around the Black Sea. He tasted his way to paradise and then recorded it in classical Greek hexameters. Not the way one might record recipes these days, but maybe he felt it added a lyrical nuance to his findings, as well as a playful parody of epic poetry.

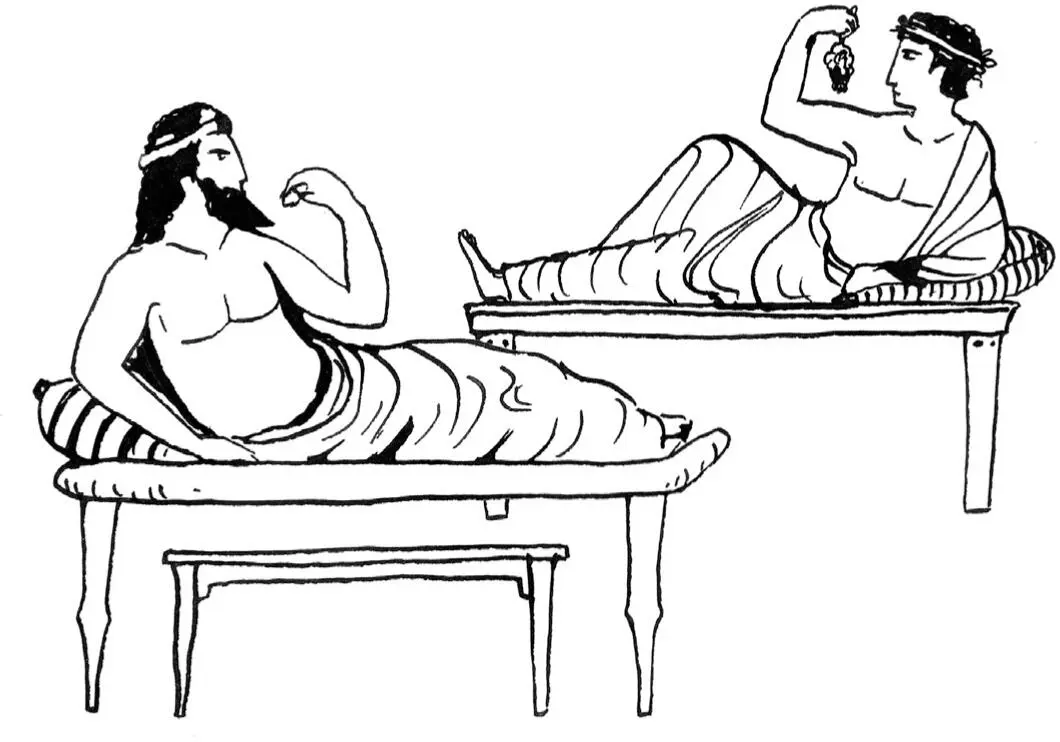

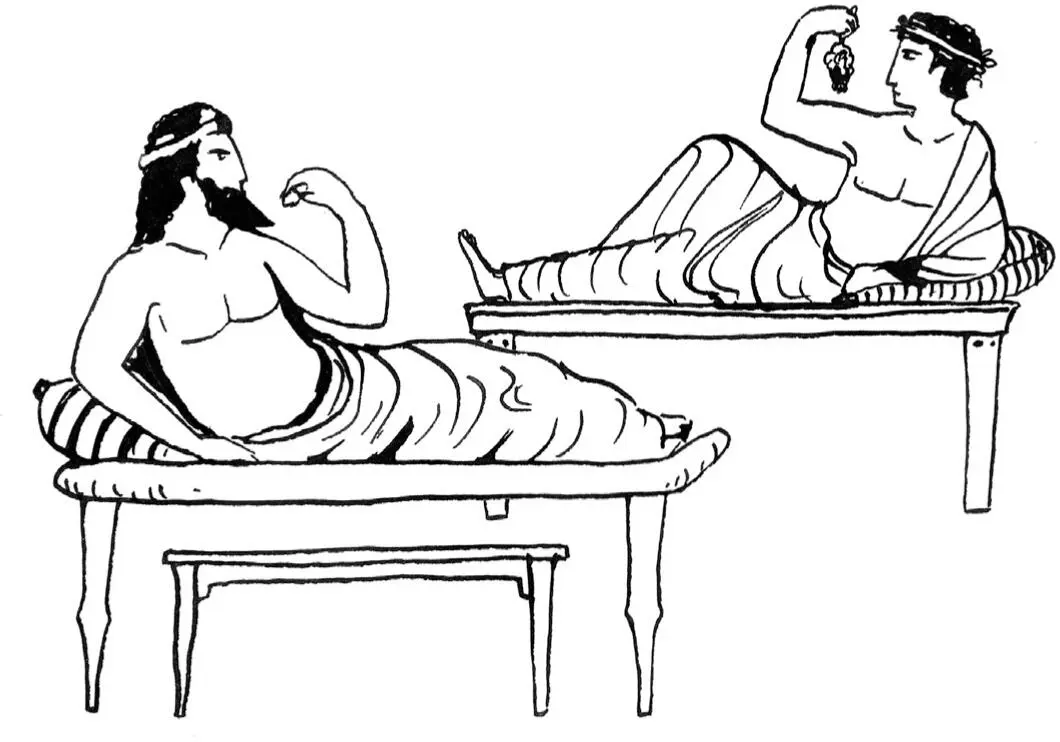

The entire project was recorded in the form of a poem appropriately entitled Hedypatheia or ‘Life of Luxury’. And while only fragments of it remain, there are enough of them for us to get a good idea of the food he ate, what he thought of it and, vitally, how it was cooked. Archestratus’s writings on ingredients, dishes and his views on flavour combinations paint a picture of the well-to-do of ancient Greece in around 350 bc. Their tastes were cosmopolitan and they appear to fit the stereotypical image of them taught at school – lying languidly on couches, eating in a reclining position, grapes dangling from their fingers.

The poem shows Archestratus to be a man of strong likes and dislikes. He was not a great eater of meat, for instance, its link with religious sacrifice making it less appealing as a dish for feasting, but he loved sea and river food. Of the sixty-two fragments that remain of his poem, forty-eight concern fish. He divided these into two categories: tough fish that needed marinating and the finer type that could be cooked straight away. And his guiding principle in cooking it was simplicity. He believed that the better quality of the raw product, the fewer additional ingredients the cook needed to add. Cooking should be simple – preferably grilling with the lightest of seasoning and oil, such as in this recipe for cooking a variety of shark: ‘In the city of Torone you must buy belly steaks of the karkharias sprinkling them with cumin and not much salt. You will add nothing else, dear fellow, unless maybe green olive oil.’ The recipe for baked fish, at the top of this chapter, is prepared with a similar lack of fuss.

‘All other methods are mere sidelines to my mind,’ he wrote. ‘Thick sauces poured over, cheese melted over, too much oil over – as if they were preparing a tasty dish of dogfish.’ Perhaps this was a rebellion against the meals he had endured as a child, which could be very rich as well as over-abundant. As Plato wrote disparagingly: ‘[Sicily is] obsessed with food, a gluttonous place where men eat two banquets a day and never sleep alone at night.’

As well as his disdain for sauces, Archestratus was insistent on what he considered were worthy ingredients. ‘Eat what I recommend,’ he said. ‘All other delicacies are a sign of abject poverty – I mean boiled chickpeas, beans, apples and dried figs.’ And he was obsessed with where food came from and where the best ingredients were to be found. ‘Let it come from Byzantium if you want the best,’ he wrote, like the voiceover of an early product endorsement.

Of the few meats he liked – hare, deer, ‘sow’s womb’ and all sorts of birds, from geese to starlings and blackbirds (animals not used for sacrifice, that is) – he preferred the following method of serving: ‘[Bring] the roast meat in and serve to everyone while they are drinking, hot, simply sprinkled with salt, taking it from the spit while a little rare. Do not worry if you see ichor [blood – used normally with reference to the Greek gods] seeping from the meat, but eat greedily.’ As with cooking fish, the principles are of a dish simply prepared and served.

Highly opinionated Archestratus may have been, but he was also extremely knowledgeable. Indeed, he demonstrated a sophisticated appreciation of the various parts of a fish, writing of the subtle differences in texture between the flesh of the fin, belly, head or tail. Subsequent writers relied on his expertise. Athenaeus of Naucratis, author of the Learned Banquet in around AD 200 and a man without whom we would have little knowledge of the cultural pursuits of the ancient world, was much influenced by his predecessor. He wrote of Archestratus: ‘He diligently travelled all lands and sea in his desire … of tasting carefully the delights of the belly.’

While his musings on food are appealingly vivacious, Archestratus’s recipe writing is deliciously free and passion-fuelled, such as when championing the finest-quality ingredients: ‘If you can’t get hold of that [sugar], demand some Attic [Greek] honey, as that will set your cake off really well. This is the life of a freeman! Otherwise one might as well … be buried measureless fathoms underground.’ Probably the world’s earliest cookbook, Life of Luxury has all the energy and colour of a modern bestseller.

5

To salt ham

160 BC

AUTHOR: Cato the Elder, FROM: De agri cultura (On Farming)

Salting of ham and ofellae [small chunks of pork] according to the Puteoli [a Roman colony in southern Italy] method. Hams should be salted as follows: in a vat, or in a big pot. After buying hams [legs of pork] cut off the hooves. Use half a modius [a dry measure equivalent to about 9 litres (2 gallons)] of ground Roman salt per each ham. Put some salt on the bottom of the vat or pot, and place the ham on it skin downwards and cover it with salt. Then, place the next ham on it skin downwards and cover it with salt in the same way. Take care that the meat does not touch … After all the hams are placed in this way, cover them with salt so that the meat cannot be seen; make the surface of the salt smooth. After the hams stay for five days in the salt, remove them all, each with its own salt. Those that were on top should be placed on the bottom and covered with salt as previously. After twelve days altogether take the hams out; remove the salt, hang them in a draught and cure them for two days. On the third day, take the hams down and clean them with a sponge, smear them with olive oil mixed with vinegar and hang them in the building where you keep the meat. No pest will attack them.

Roman politician Marcius Porcius Cato was brought up on a farm south-east of Rome near a city called Tusculum. He enlisted as a solder at seventeen and later rose to high office as a statesman, known as a skilful orator who made use of his public-speaking prowess by chastising those in the Senate whom he felt were too liberal. This accorded with his latter role as censor, an official position that included supervising public morality and which he took to with enthusiasm. With his clamp-down on immoral officials and support of a law against luxury, he was identified with the job – known to posterity as Cato the Censor. He was censorious about those he thought were extravagant – he wouldn’t have approved of the creamy sauces that came out of Apicius’s kitchen 150 years later – while the first-century historian Plutarch praised him not for any triumphs as military leader but that ‘by his discipline and temperance, [he] kept the Roman state from sinking into vice’.

Читать дальше