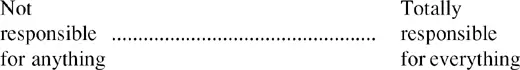

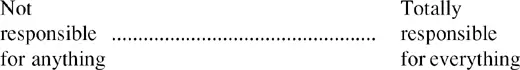

So we have to find a balance between being

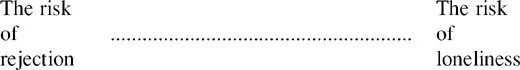

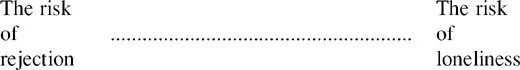

Even though from the moment of birth we need other people, as small children we soon learn that other people can reject and punish us, and this can be very painful. We protect ourselves from this pain by becoming very careful in our relations with other people. We withdraw from them, and when we deal with them we put on some sort of social front. When I was researching for my book Friends and Enemies 1 I questioned a large number of people about the part friendship played in their lives. Many of these people spoke of how, while they valued their friends and dreaded loneliness, they feared being rejected or abandoned or betrayed by their friends. Being close to other people is risky, but then we also run the risk of loneliness.

So we have to find a balance between

Thus in these six vital aspects of our lives we are for ever trying to achieve a balance between two opposites. There is no textbook we can consult which will tell us what is the right balance, because what is right for one person is wrong for another. We cannot, when we are, say, fifteen, arrive at a set of balances which will suit us for the rest of our lives and stick with that, because what is a good balance at fifteen is not so good at twenty and quite disastrous at forty. So we have to keep trying to find the right balance, and we always run the risk of getting it wrong. We are always in the position of the juggler who is trying to keep eight oranges in the air while balancing on a ball which is on a chair which is resting on a plank which is supported by two rolling drums which are on a raft floating in deep water. Any minute, something could go wrong. It is no wonder that we often feel frightened.

We struggle on, meeting what seems an endless stream of difficulties and problems. When we encounter yet another setback, we often look at other people and see them being like those people in the television advertisements who are always beautiful, knowledgeable, organized, intelligent, happy, loved, admired and suffering no greater problems than choosing the right margarine and coping with the weather. Then we can feel just like Alice when she met a couple at a dinner party.

‘They’ve got three children,’ she told me, ‘and they’re all brilliant, marvellously musical, getting excellent degrees, entering wonderful careers. He’s done terribly well, she’s got this marvellous part-time job and she’s got paintings in this new exhibition. Everything that family does is just right. Urgh!’

It is hard not to feel envy for people whose lives seem to go along more easily, more successfully than ours. However, this is the price we pay for clinging to the hope that it is possible for us to find a way of life where we are happy, trouble free and never make a mess of things. Without this hope many of us would find life very difficult indeed. The alternative version of life, in which all of us suffer one way or another, have heavy burdens and often make a mess of things, can rob us of hope and make us feel very frightened.

Many of us, as we get older, come to agree with Samuel Johnson that ‘Human life is everywhere a state in which much is to be endured and little to be enjoyed’, and try to meet this view of life with courage and hope. However, those of us who have read about Johnson know that during his life he was often depressed and that he was always afraid of dying.

Most of us go through a large part of our lives not thinking about death. ‘When it comes, it comes,’ we say, and secretly think that it will not. Other people die in earthquakes or car accidents or of cancer or of old age, but not me. I am the exception. Then one day something happens and we know. Death means me.

Then all the careful security we have built up comes crashing down. We are all alone, without protection, open to great forces which we cannot and do not understand. We ask in our anguish, ‘Why me?’ ‘Why death?’ ‘Why life?’ ‘What is it all about?’ There are no satisfactory answers.

From the moral and religious education we received in childhood many of us drew the comforting conclusion ‘If I’m good nothing bad can happen to me or to my loved ones’. When death becomes imminent, or some other terrible disaster strikes, our belief in the protective power of virtue is swept away.

Rose’s lawyer asked me to prepare a report on how Rose had been affected by her accident. She was having difficulty in getting back to work.

Rose said to me, ‘The car pulled out of the driveway and hit me as I was cycling past. My bike was caught under the front of the car and I was pushed across the road. I could see the lights of other cars coming towards me. I remembered how, when I was eight, we left our beautiful home in the country and moved to London. And then I thought, “I won’t have any more holidays.” I ended up in the gutter on the other side of the road. A man came to pick me up and I thought he was the driver of the car. I gave him a mouthful. I was angry and then I found that he wasn’t the driver… I feel so guilty about all of this, putting all you people to so much trouble. You’ve got people who need your help far more than I do. I’m all right, really, just my back’s a little sore and I get a bit weepy now and then. I usen’t to be like that. Always self-controlled, really. Now I think, why me? Why do I go on living and those babies die?’

Rose was not all right. She was shaken to the very core and guilty that she was alive. That sounds crazy, but it is what many people think when they have survived a terrible disaster. ‘Survivors’ guilt’ is now a common term, derived from studies of the people who survived the concentration camps of the Second World War, or Hiroshima and Nagasaki (the hibakusha) , or the fighting in the Vietnam War. 2Such people feel, not joy at being alive, but fear, fear that they have done something wrong, for they ought to have died like their companions, fear that they have been given something they do not deserve and that they will be punished for holding on to it or that it will be suddenly taken away from them. They may have survived, but death as retribution is imminent.

Rose’s question ‘Why me?’ was that of an ordinary woman nearing sixty who had worked diligently all her life, looking after her family, being competent in her office work, enjoying a quiet life in a country town, never expecting that her life would have any other significance than the pattern of the lives of her family and friends.

Then suddenly she was flung, not just across a road in the path of oncoming cars, but into the vast mysterious universe of being. Why me? In all this vastness, why me? Alone in all that vastness, she trembles with fear. Has she been saved for some purpose? Is there some pattern, some Grand Design, in which she has to play a significant role? If there is, why is she, an ordinary woman, chosen to play it? Will something be asked of her that she cannot perform, where she will fail and be punished for her failure? Has the Grand Designer got it wrong? Was she saved by mistake? Has she been given something that she doesn’t deserve? Should she be dead, and some little baby, now dead, be alive? Or is there no design, just a random universe where some people live and others die, with no justice or fairness or reward for goodness and punishment for badness? Just randomness, chance without significance, life without meaning? Is ‘Why me?’ a question flung at the stars, and the stars shine coldly back with no answer?

Читать дальше