ERIC NEWBY

Copyright

Copyright

Harper Press An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd. 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

This Harper Press edition published 2011

First published by HarperCollins Publishers in 1994

First published in by Picador in 1995

Copyright © Eric Newby 1994

Wine label by Jonathan Newby

Eric Newby asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollins Publishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007367900

Ebook Edition © FEBRUARY 2013 ISBN: 9780007508150

Version: 2017-01-04

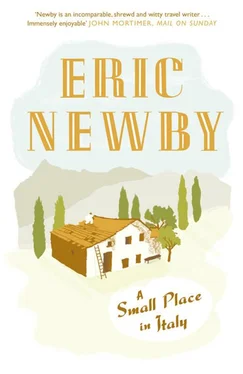

From the reviews of A Small Place in Italy:

‘Eric Newby must rank as one of the foremost travel writers of our age. Among his skills lies the ability to carry the reader with him on the most varied of journeys … Newby’s good humour, and his loving eye for a way of life now disappearing, makes it a sterling contribution to that very particular shelf of English literature, describing life as lived among the Italians’

HUGH CARLESS, Guardian

‘Newby is of course a travel writer of near genius – wonderfully dry in the narration of the tribulations which so often afflict him and Wanda, and splendidly precise on the nuts and bolts of things … Highly readable and dangerously liable to induce a craving for one’s own patch of Italian paradise’

MARTIN GAYFORD, Sunday Telegraph

‘Beautifully written. Full of wisdom, humour and humanity, Newby is touching on the poignancy of life, its fleeting pleasures and ultimate, inevitable loss … He is a perceptive interpreter of our dreams’

Sunday Express

‘A jovial account of living in Tuscany’

Literary Review

‘Newby goes into satisfying detail about the people, the food and the landscape, and the house itself takes a central role in the book … By observing the details of his surroundings with clarity and understanding, he gives the reader a gentle picture of a pleasant Arcadia’ Wanderlust

To all our friends at I Castagni

whom we will never forget

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Praise

Dedication

Epigraph

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-One

Twenty-Two

Keep Reading

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Also by the Author

About the Publisher

My dear little house

you were not there before

but in a short time you have grown

like a flower.

I beg you to remain

beautiful

and not to lose your colour.

I am about to go

because I have

a call from far away

but I will carry you

in my heart

for eternity.

Goodbye my little house.

Goodbye happiness.

Giuseppe Tarsiero, 1981

In August 1942, whilst serving with the SBS, I was captured during a raid on a German airfield in Sicily, a year before the Allied landing took place.

In September 1943 the Italian armistice was announced and the following day, on 9 September, together with all the other inmates of the camp in the Po Valley near Parma, I absconded in order to avoid being sent to Germany, as did thousands of other prisoners-of-war in camps all over Italy.

The one thing that most of these escaping prisoners had in common in the course of the succeeding months was the unstinting help they were given by all sorts and conditions of Italians who risked their lives in doing so without any thought of subsequent reward. One of these, a girl called Wanda, subsequently became my wife.

Once out beyond the barbed wire, which up to that time had effectively insulated me and my fellow prisoners from the country and its inhabitants, and after I had been transported high into the Apennines, I found myself in a little world inhabited by mountain people whose way of life was of another century. A world in which there were few roads, scarcely any machinery of a labour-saving kind, one in which everything connected with working the land was accomplished with the aid of mules, cows and bullocks. Even wheeled vehicles were only of limited use. In these mountains the most common method of transportation was wooden sledges. It was a world in which when the snow came the inhabitants were cut off for long periods of time. Living with these people I gradually began to understand their way of life and their closely knit society.

But not for long. In January 1944 I was re-captured by one of the armed bands of Fascist Milizia, supporters of Mussolini’s puppet republic of Salò, which continued to function until he himself was captured and shot during the last days of the war in Italy in 1945. From Italy I was sent to Moosburg, a vast prison camp in the marshlands near Munich, then to a place in what had been Czechoslovakia but was now Silesia, which the Germans called Märisch Trübau, what the Czechs had known in happier days as Moravská Trebová. From here, after a series of terrible events which resulted in the deaths of two officers, we were moved en masse to a camp near Braunschweig in western Germany where finally, on 14 April 1945, 2400 of us were liberated by the Americans.

At the end of 1945 I managed to get to Italy where Wanda was already working for an organization known as M19 whose job, now that peace had come, was to seek out and help civilians who had helped escaping prisoners-of-war. Once again I found myself, and this time with Wanda, entering into the world of the contadini in the Apennines above Parma which by now I had grown to know so well.

In 1946 we were married in Florence, and ever since that time we have continued to visit the people who helped me all those years ago.

While I was a prisoner in Germany I thought constantly of a day when the two of us might be able to return to the mountains and buy a house of the sort I had been hidden in and lived in while I was on the run. In February 1945, one of the last few awful months of the war in Germany, I wrote in my diary, imagining such a house:

It is an evening in late November. Outside the wind has risen, tearing through the trees about the house, bringing rain drumming against the window panes. The lamp is out and the fire casts enormous shadows on the ceiling and on the bookshelves, lined with much-read books.

Читать дальше

Copyright

Copyright