“The death of the contemporary forms of social order ought to gladden rather than trouble the soul,” writes Aleksandr Herzen, the Russian political philosopher, in From the Other Shore . “But what is frightening is that the departing world leaves behind it not an heir, but a pregnant widow.” Herzen was writing of the European revolutions of 1848, but his words echo across Russia today. “Between the death of one and the birth of the other,” he concludes, “much water will flow, a long night of chaos and desolation will pass.”

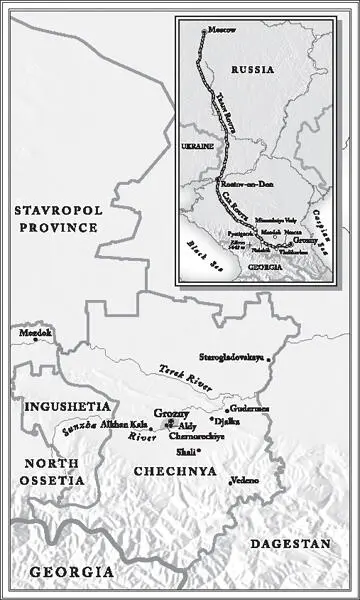

I stared at the huge map on our wall at home and plotted my route. I would travel to the country’s extremes, to the corners where no “Kremlin insiders” dwelt and few oligarchs set foot. I wanted to go to the Russian lands where no one had dined with Berezovsky or vied for an audience with Luzhkov, where few cared about the Byzantine struggles that entranced Moscow and fewer still fretted about the price of Siberian crude on the world exchange. I wanted to go to the regions where Russians had seen little of the rewards of the new era but felt much of its pain. I wanted to listen to the land’s survivors and survivalists, to those who lived in its far-flung corners without the slightest expectation that anything good should ever come to a people who deserved so much better.

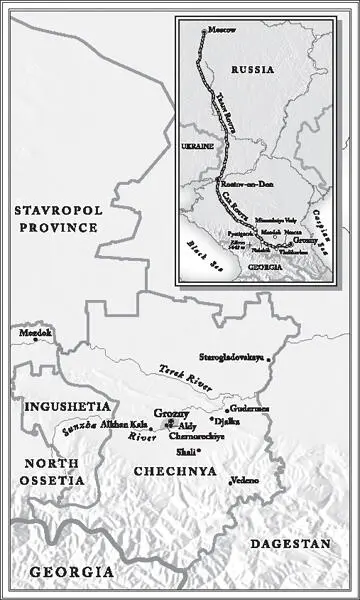

II. SOUTH TO THE ZONE

WE WERE, AT LONG LAST, on the outskirts of Aldy, an ancient village of overgrown fruit trees and low-slung tin roofs on the southern edge of Grozny, the Chechen capital, and Issa was singing, “ Moi gorod Groooozny, ya po tebe skuchaaayu … no ya k tebe vernuuus, moi gorod Grozny moi .”

He was an imposing figure, just over six feet, his chest and shoulders so broad he appeared taller. Issa liked to keep his silvering hair shaved on the sides of his head and at the back of his neck. The cut lent him the stern air of a military man or a Soviet bureaucrat of stature, an image, as was no doubt the intent, to intimidate at the checkpoints. More often silent, Issa broke into song when the air around him grew too quiet. Now, just as the roadblock, the last one before Aldy, rose into view, Issa was singing at the top of his lungs.

“ Moi gorod Groooozny ,” he wailed. “My city, the city of Grozny, oh, how I miss you, but I shall return to you …”

There were four of us in the rattling Soviet Army jeep, known endearingly as a UAZik, pronounced wahzik , in the common parlance. Lord knows what image we projected to the well-muscled, sunburned, and deeply suspicious Russian soldiers at the checkpoints. Sometimes they were drunk. Nearly always they were scared. In Chechnya, I’d learned, checkpoints were the measure of one’s day. People did not ask, “How far it is?” but “How many checkpoints are there?” Each day we crossed at least a dozen.

On this sweltering morning in July, we had already passed seventeen. The posts were the center of activity amid the ruins of the city. Conscripts maintained the constant vigil, checking the cars and their passengers, while their officers, hands on radios, sat in shaded huts off the road. But this post was nearly empty, and the OMON officer who stopped us, a pit bull from Irkutsk, was not in a good mood. His arms and neck glowed with the burned pink skin of a new arrival. He wore wraparound sunglasses and a bandanna over his shaved head. Tattoos, the proud emblems of Russian soldiers and prisoners, covered his biceps. “ Slava ” (“glory”) adorned the right one. It could be a name or a desire. He wore no shirt, only a green vest fitted with grenades, a knife, and magazine clips to feed the Kalashnikov he held firmly in both hands. His fingers seemed soldered to it.

We may have looked legit, but we were a fraud. Issa ostensibly was a ranking member of the wartime administration in Chechnya, the Russians’ desperate attempt at governance in the restive republic of Muslims, however lapsed, Sovietized, and secularized. He had the documents to prove it, but the man who signed them had since been fired. Issa knew the life span of his documents was limited. At any checkpoint his “client,” as he had taken to calling me, could be pulled from the jeep, detained, interrogated, and packed off on the next flight to Moscow.

At fifty-one, Issa boasted a résumé that revealed the successful climb of a Chechen apparatchik. Born in Central Asian exile, in Kyrgyzstan, five years after Stalin had deported the Chechens in 1944, he had graduated from the Grozny Oil Institute in 1971. For twenty-one years he worked at Grozneft, the Chechen arm of the Soviet Oil and Gas Ministry. He spent the last Soviet years, until Yeltsin clambored onto the tank in 1991, in western Siberia, overseeing the drilling of oil wells in Tyumen. He spoke a smattering of French, a bit of Arabic, and a dozen words in English – all learned, he liked to tease, during stints in Iraq and Syria.

As the Soviet Union collapsed, life went sour fast. Djokhar Dudayev – the Soviet Air Force general who was to lead the stand against Moscow – returned to Grozny, and the fever for independence seized the capital. Issa, then a director of one of Chechnya’s biggest chemical plants, took up arms against the insurgents. In the fall of 1993, more than a year before Yeltsin first sent troops into Chechnya, with Moscow’s backing Issa and his fellow partisans rallied around a former Soviet petrochemicals minister and staged a pathetic attempt to overthrow Dudayev. 1

He was careful not to dispense details, but the scars were hard to hide. His right forearm had a golf ball-size hole, remnants of a bullet taken on the opposition’s line north of Grozny in September 1993. The bullet had pierced his arm and lodged in his left shoulder. A few months later Dudayev’s freedom fighters got him again. Kalashnikov fire had ripped his stomach, intestine, and lungs, leaving a horrific gnarl of tissue in the center of his body. He’d moved his family-a wife, two boys, and a girl – to Moscow. But he wanted to be clear: He never wanted to fight. “We never loved the Russians,” he said. “We just hated that corrupt little mafiya shit.” He was speaking of Dudayev, the fallen independence leader, the man many Chechens, much younger and more devout, now called the founding martyr of the separatist Islamic state, the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria, as Dudayev had ordered his native land rechristened. 2

In front of me, behind the wheel, sat Yura. Projecting a genuine sweetness, he was a good-looking kid with blue-green eyes and blond hair that his mother cut short each week with a straight razor. He had thin cheeks, covered with freckles and shaded by the beginnings of a beard. Just twenty-two, he was lucky to have made it this far. He belonged to one of the world’s most unfortunate species; he was an ethnic Russian born in Chechnya. “Our Mowgli,” Issa had jibed, equating Yura with Kipling’s jungle boy. Everyone laughed. There was no need to explain. Mowgli was raised by wolves. The Chechens, centuries ago, had made the wolf their mascot, the embodiment of their struggle.

The last of the crew, bouncing beside me in the back seat of the car, was Shvedov. It was a last name – few ever learned his first – that meant “the Swede.” There was nothing, however, Swedish about him. He had a tanned bald head and a scruffy dirty brown beard and mustache. He carried an ID from the magazine the Motherland , but his paid vocation was what is known in the field as a fixer. For decades he earned a living, or something approximating it, by getting reporters in and out of places they had no business being in. Usually genial and often hilarious, he could be brilliant. But Shvedov’s greatest attribute was that he did not drink. I had known him for years but never traveled with him. After only three days I discovered my own heretofore unknown homicidal urges coming on strong. Somehow I had missed Shvedov’s worst sin: He talked without pause. (When he did not talk, he clacked his upper dentures incessantly on a set of lower teeth blackened by a lifetime of unfiltered Russian tobacco.) A colleague who traveled with him often had offered a tip: “Keep a cigarette in his mouth.” But even smoking, Shvedov talked.

Читать дальше