When New Yorkers insisted on honouring the 77th anyway, the War Department advanced a series of pretexts to block them. It said the doughboys themselves did not want a parade. The men, once asked, were unanimously in favour. War Secretary Newton Baker then cited objections by Fifth Avenue shopkeepers to the erection of grandstands between 97th and 98th Streets. After the courts rejected the shopkeepers’ injunction, the department claimed the parade would be too expensive – almost a million dollars, a figure soon lowered to $80,000. Finally, it said that disembarking 30,000 men at the same time would paralyse the docks.

War Department prevarications infuriated New York City. All of the 77th’s boys came from the metropolis, whereas the 27th’s National Guardsmen hailed from as far as Schenectady and Albany. Meetings assembled throughout Manhattan to lodge protests. The Welcome Committee for the Jewish Boys Returning from the War sent an urgent telegram to Secretary of War Baker: ‘The East Side, which has contributed so large a quota to this division, is stirred at being deprived of the opportunity to pay tribute to this division … We strongly urge you to do everything within your power to make it possible that the parade shall take place. It will be an act of patriotism.’ The next day, the Committee cabled President Woodrow Wilson ‘as Commander in Chief of the US Army, to rescind the order prohibiting the parade of the 77th Division. The people of the east side have gladly given their sons to do battle in France for their country, and desire to pay loving tribute to the boys who are returning and to the memory of those who sleep on foreign soil.’

Charles Evans Hughes, a former Supreme Court justice and the Republicans’ nominee for president in 1916, chaired a gathering of the Selective Service Boards that had conscripted the men of the 77th two years earlier. ‘We want to do for the 77th what we did for the 27th,’ Hughes declared. ‘There should be no desire to discriminate against any of the boys who went to the front, from New York or any other place.’

No one contested the division’s achievements: more than two thousand of its men had been killed, and another nine thousand wounded – more than double the casualties sustained by the 27th. They were one of the first American divisions sent into combat and the only one at the front every day of the Meuse-Argonne offensive. The New York Times wrote of the mostly immigrant troops: ‘The 77th fought continuously from the time it entered the Lorraine sector in June [1918] until it stood at the gates of Sedan when the armistice was signed. It drove the Germans back from the Vesle to the Aisne River. It rooted them out of the very heart of the Argonne Forest. And it ranked seventh among the [twenty-nine] divisions that led in the number of Distinguished Service Crosses awarded for gallantry in action.’ When they launched an assault against the Germans along the River Vesle, called by the troops ‘the hellhole of the Vesle’, General Erich Ludendorff unleashed the phosgene and mustard gas that blinded and crippled thousands of Allied soldiers. William Weiss was one of them, taken out of the front with eyes bandaged from the stinging pain of the poisons and his leg nearly shot off by German rifle fire.

The heroism of New Yorkers like Private Weiss gave the lie to military orthodoxy, as stated in the US Army’s official Manual of Instruction for Medical Advisory Boards in 1917, that ‘the foreign-born, and especially the Jews, are more apt to malinger than the native-born’. Dr William T. Manning, chairman of the Home Auxiliary Association, told a meeting in New York that soldiers’ families felt their sons were victims of racial discrimination. Woodrow Wilson, a Southern gentleman whose administration had introduced segregation by race into the federal civil service in 1913, was impervious to accusations of bias. In his State of the Union Address for 1915, the Democratic president had said, ‘There are citizens of the United States, I blush to admit, born under other flags but welcomed under our generous naturalization laws to the full freedom and opportunity of America, who have poured the poison of disloyalty into the very arteries of our national life; who have sought to bring the authority and good name of our Government into contempt … Such creatures of passion, disloyalty, and anarchy must be crushed out.’ Neither the all-black 369th Regiment, known as the Harlem Hellfighters, nor the mostly foreign-born 77th Infantry Division won the president’s admiration, although both had earned more decorations than most all-white, ‘all-American’ units.

Public clamour grew so loud that the War Department backed down. The division’s troopships docked at the end of April, and on 6 May the men assembled downtown for one of the biggest parades in New York history. Schools closed, and workers came out of their bakeries, laundries and garment shops to lionize the boys who had won the war to end all wars. With rifles on shoulders and tin hats on heads, the men of the 77th marched five miles up Fifth Avenue from Washington Square to 110th Street past more than a million well-wishers. Usually called the Liberty Division for their Statue of Liberty shoulder patches, and sometimes the Metropolitan Division, they were now ‘New York’s Own’. ‘Every building had its windows full of spectators, waving flags or thrown out [sic] torn paper, candies, fruit, or smokes,’ the New York Times reported. ‘Most of the store windows were tenanted by wounded veterans or their relatives, while park benches were placed at choice sites for men from the convalescent hospitals.’ Some of the 5,000 wounded rode in open cars provided by local charities, while others moved on crutches and in wheelchairs. Lest the 2,356 buried in France be forgotten, the procession included a symbolic cortège of Companies of the Dead.

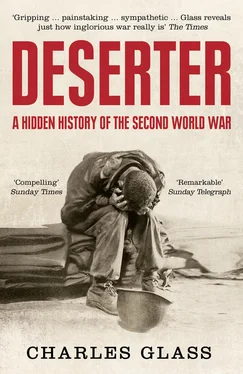

Only the deserters, a mere 21,282 among the whole American Expeditionary Force of more than a million men, went unacknowledged. Most were in army stockades or on the run from the Military Police in France. Of the twenty-four American soldiers condemned to death for desertion, President Wilson commuted all of their sentences. The Great War had a lower rate of desertion, despite its unpopularity in many quarters, than any previous American conflict. More British and French soldiers had run from battle, but their four years in the trenches outdid the Americans’ one. Britain shot 304 soldiers for deserting or cowardice and France more than 600. In the 77th Division, only a few men had left their posts in the face of the enemy. Perhaps out of shame, the division referred to most of them as Missing in Action.

When the parade ended at 110th Street, the 77th’s commander, Major General Robert Alexander, declared, ‘The time has come to beat the swords into plowshares, and these men will now do as well in civil life as they did for their country in France.’

Not all of the men would do as well in civilian life as they had in France. The division’s most decorated hero, Medal of Honor winner Lieutenant Colonel Charles Whittlesey, committed suicide in 1921, a belated casualty of the war. Others died of their wounds after they came home, and some would remain crippled or in mental institutions for the rest of their lives. Many enlisted men, unable to find work, drifted west. Among them was William Weiss, who at the age of twenty-seven left home as much to forget the war as to earn a living. The wounded veteran worked as a farmhand in the Kansas wheat fields, then followed the oil boom to Oklahoma and Texas as a roustabout. This led to a stint with the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, which had been subsumed into the Treasury Department’s Prohibition Unit in 1920. Among the unit’s duties was the interdiction from Mexico of newly illegal drugs like marijuana and alcohol. Something happened in El Paso that compelled Weiss to resign, an episode that he concealed even from his family. He moved back to New York, where he married a young woman named Jean Seidman in 1923. On 3 October 1925, the couple had a son, Stephen James. The family called him Steve, but his mother nicknamed him ‘Lucky Jim’. Five years later, the boy was followed by a daughter, Helen Ruth.

Читать дальше