As women become more ambitious for themselves, they talk disparagingly about what they call ‘herbivore men’ ( soˉshoku-kei danshi ), a term coined in 2006 by the Nikkei columnist Maki Fukasawa. The herbivore man doesn’t know how to ask a woman out on a date. He’s intimidated by women. And, the implication is, he’s not even that interested. A survey in the Japan Times found 20 per cent of men in their late twenties reported having little or no interest in sex – some citing crippling long working hours. 11

It’s not clear to what extent the stereotype is true. There are still plenty of Love Hotels, the Japanese hotels which were created for salarymen to grab some respite. And the number of children produced by married couples is still hovering around replacement rate. But far more people are staying single. As arranged marriages disappear, hundreds of thousands of men whose mothers would once have found them a bride are struggling to adapt. One in four 50-year-old Japanese men has never been married. 12Since this is a country which still feels uncomfortable having children out of wedlock, that’s bad for birth.

Having children is also a costly business. In surveys, 20- and thirty-something men and women 13say lack of money is a serious obstacle to getting married. Couples increasingly need two incomes. But it’s hard to combine a career with motherhood in a culture where people stay at their desks late.

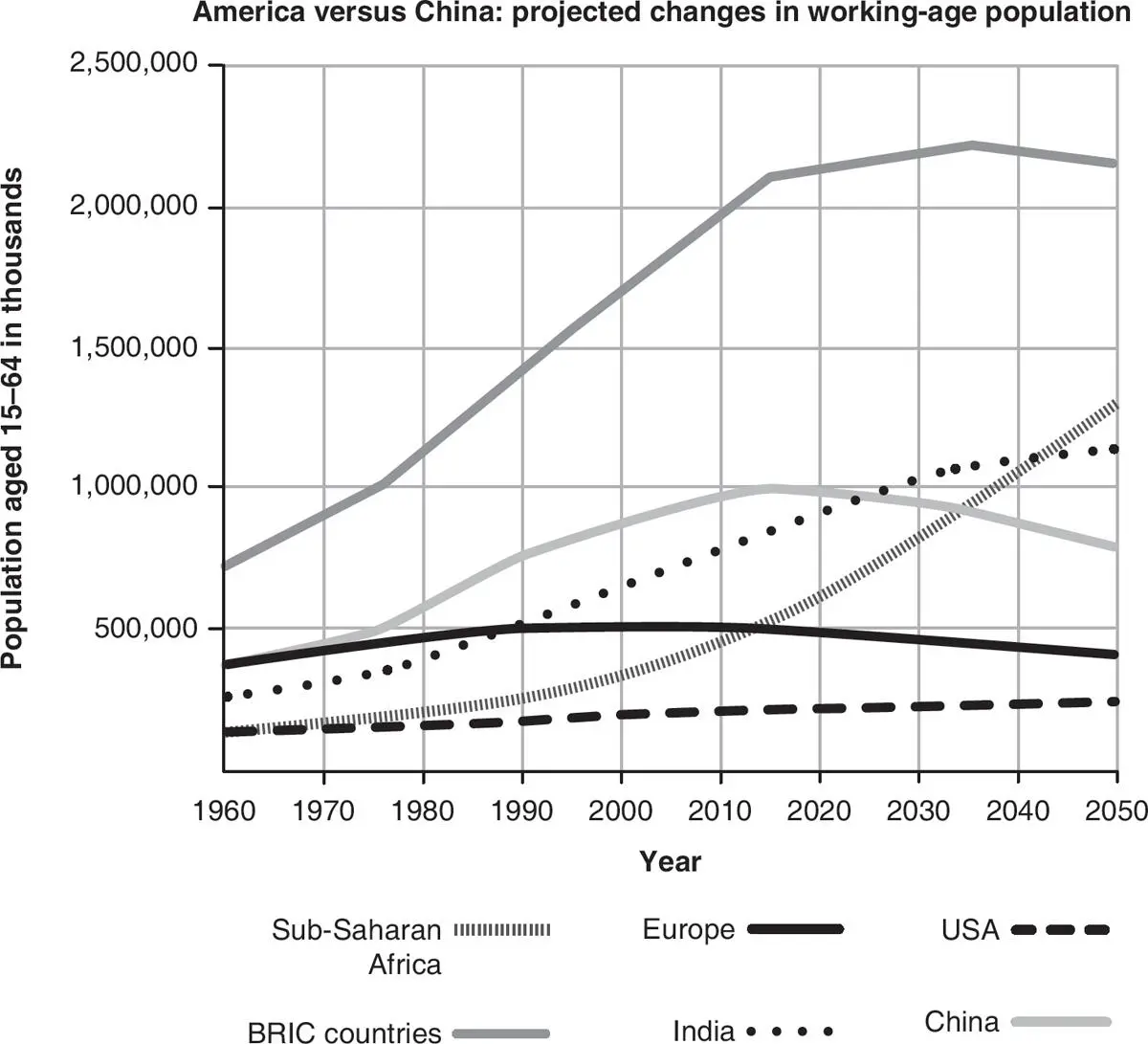

Cost is not the whole story. Many women have been liberated from the need to find a husband to support them, as employers have become more open-minded about hiring. This partly stems, ironically, from the realisation that Japan must utilise all its talents if its economy is to prosper as the population shrinks. As all the curves on the graph turn downwards, experts are now looking desperately for solutions.

‘We must increase immigration, or we will see our nation vanish,’ says Dr Jun Saito, a leading economist at the UCLA Japan Center in Tokyo. Dr Saito believes that Japan must import more foreign workers even if it manages to increase the number of women and older people in the work force. ‘Even if we raised the fertility rate to 2.1 tomorrow,’ he tells me, ‘an option that is difficult to achieve, the population would not stabilize until 60 to 70 years later.’

Japanese reluctance to admit immigrants is legendary. Fewer than 2 per cent of the country’s workforce is foreign. Although the government recently created new visas for low-skilled foreign workers in industries like construction and care, and has broken a taboo by letting those workers bring their families immediately, rather than after five years, the numbers are a trickle. Only 18 foreign workers have qualified for the care-worker visa, partly because the exams are in Japanese.

‘The worst scenario in my mind,’ Dr Saito confides, ‘is that even if we open up the country, nobody comes.’

China: Growing Old Before It Gets Rich

They call it the grey wall of China. By 2100, China’s elderly population will dwarf that of any other country except India. It’ll be so large, wags joke, that you’ll be able to see it from outer space. At the park around Beijing’s Temple of Heaven, in the cool of early morning, hundreds of older people are playing cards, doing tai-chi or exercising. A group of about 50, mainly women, dance to lilting music. They move gracefully, quietly, in a choreographed routine, on the paths between the trees.

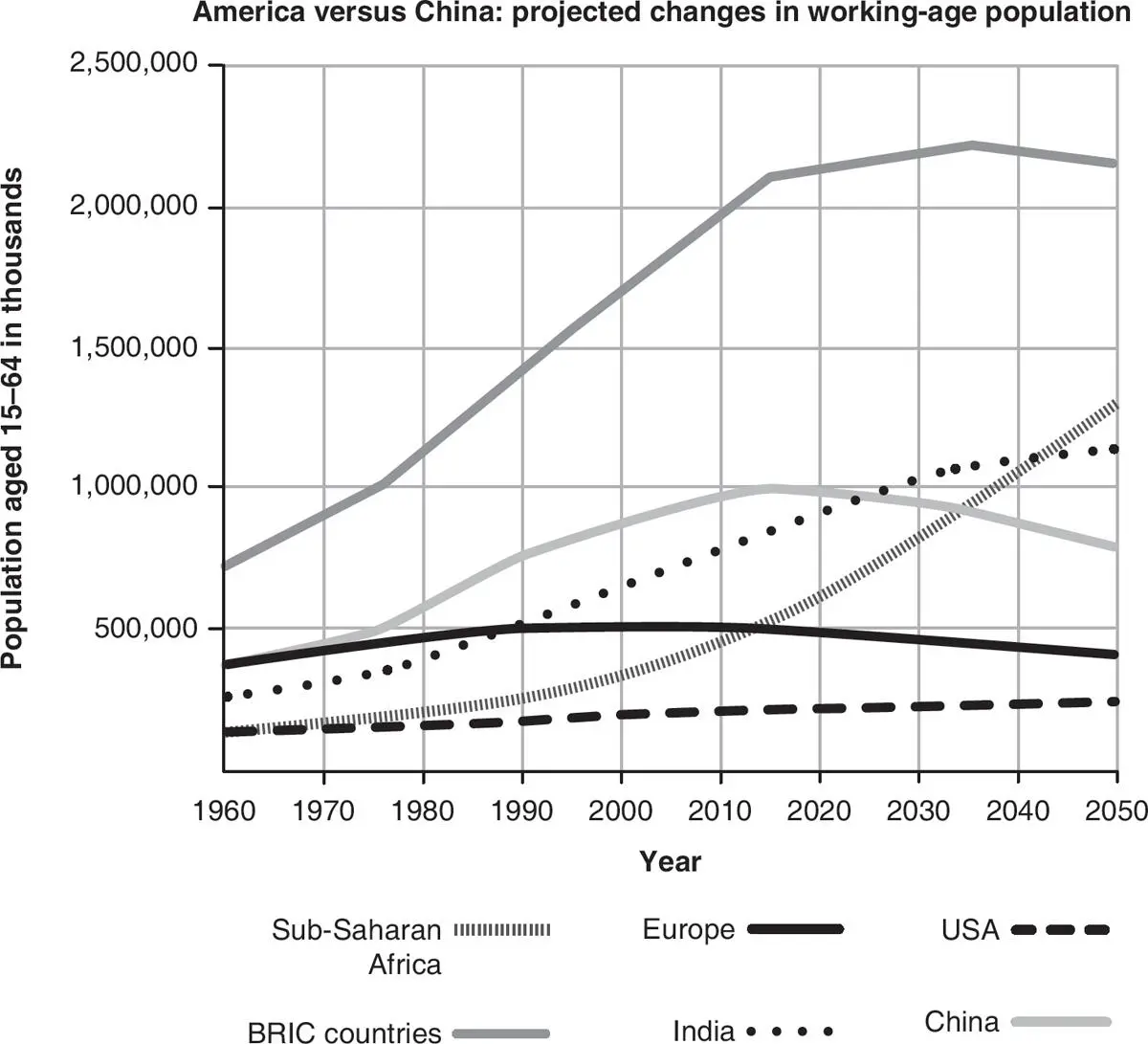

It’s an uplifting, harmonious scene. The women place their feet confidently, and with precision. But it’s hard to feel so confident of the future. Most of the people in this park are retired. China’s working-age population has been in decline since 2012 14and is set to fall by almost a quarter by 2050. The demographer Nicholas Eberstadt, of the American Enterprise Institute, has predicted that this will drag down China’s GDP growth rate. By mid-century, China’s population could look much more like Japan’s – but without Japan’s affluence.

The birth rate was falling even before the government introduced the One-Child Policy in 1978. Now, China is awash with only children. Many find themselves having to support two parents and four grandparents – known as ‘the 4–2–1’ problem. There is the added, disturbing glut of bachelors because so many families preferred sons to daughters. These ‘ guang gun ’ (bare branches) will struggle to find brides.

Sensing the danger, the Communist Party dropped the One-Child Policy in 2015. But it is probably too late. Few eligible families have applied to have a second child. Many don’t feel they can afford it, because so many have moved to cities where the cost of living is high. Seven in ten Chinese mothers work, with little time for an extra child.

Marriage is becoming less attractive. On TV dating shows like If You Are the One , successful Chinese women criticise potential suitors for being ugly or poor. More women than men now attend Chinese universities, and many are defying the jibes about unmarried women being ‘ shengnu ’, or ‘leftover’. A survey by the Chinese dating website Baihe.com has found 75 per cent of women saying that any husband should earn twice as much as them.

The Chinese Academy of Social Sciences predicts that the Chinese population will peak at 1.44 billion in 2029 before entering ‘unstoppable’ decline. 15By 2065, it says, the population will have shrunk to the levels of the mid-1990s.

What could this mean for China as a military power? Mark L. Haas, a political scientist at Duquesne University, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, has suggested that China could be forced to make ‘geriatric peace’ with other nations, as it becomes too burdened by its elderly to maintain military spending. That is not certain: China may not feel beholden to spend as much as a democracy on older citizens, and it can use technology to raise productivity. But it is too big to be able to level the playing field by importing enough immigrants.

Instead, the government has started offering five-year multiple-entry visas to tempt its diaspora back home – something South Africa and India are also doing. 16It is also contemplating raising the retirement age, which is 60 for men and 55 for women. 17

Will they be fit enough? China faces an increasing burden of chronic disease approaching Western levels. Junk food and stress have accompanied rapid urbanisation and the country has not yet broken the smoking habit. Under Mao, China’s population was surprisingly healthy: it saw the world’s most sustained increase in life expectancy, from 35 in 1949 to 65 in 1980. 18That healthy, working-age population helped to drive its unprecedented economic growth. 19But now, China is growing old with neither Japan’s wealth nor its health, at a time when many of its jobs still require physical, manual labour. And its rival, America, is on a different path.

China v America

America has long been a demographic exception, with a higher birth rate than most other rich countries. China’s population is currently around four times the size of America’s. But that gap will have halved 20by the end of this century, unless America slams the door shut on immigrants.

The chart below gives a glimpse into the geopolitics of the next few decades. It shows China’s working-age population dropping, along with Europe’s, while America’s remains stable:

Before the financial crisis, the American population was sustaining itself, with a birth rate of 2.12. 21This is partly because it has higher levels of immigration, and because immigrants tend to have larger families. In the US, 23 per cent of births are to foreign-born women, 22while only 13 per cent of the population is comprised of immigrants. 23

Читать дальше