FIRE AND BRIMSTONE

The North Butte Mining Disaster of 1917

Michael Punke

Published by The Borough Press

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by The Borough Press 2016

Originally published in 2006 by Hyperion Books

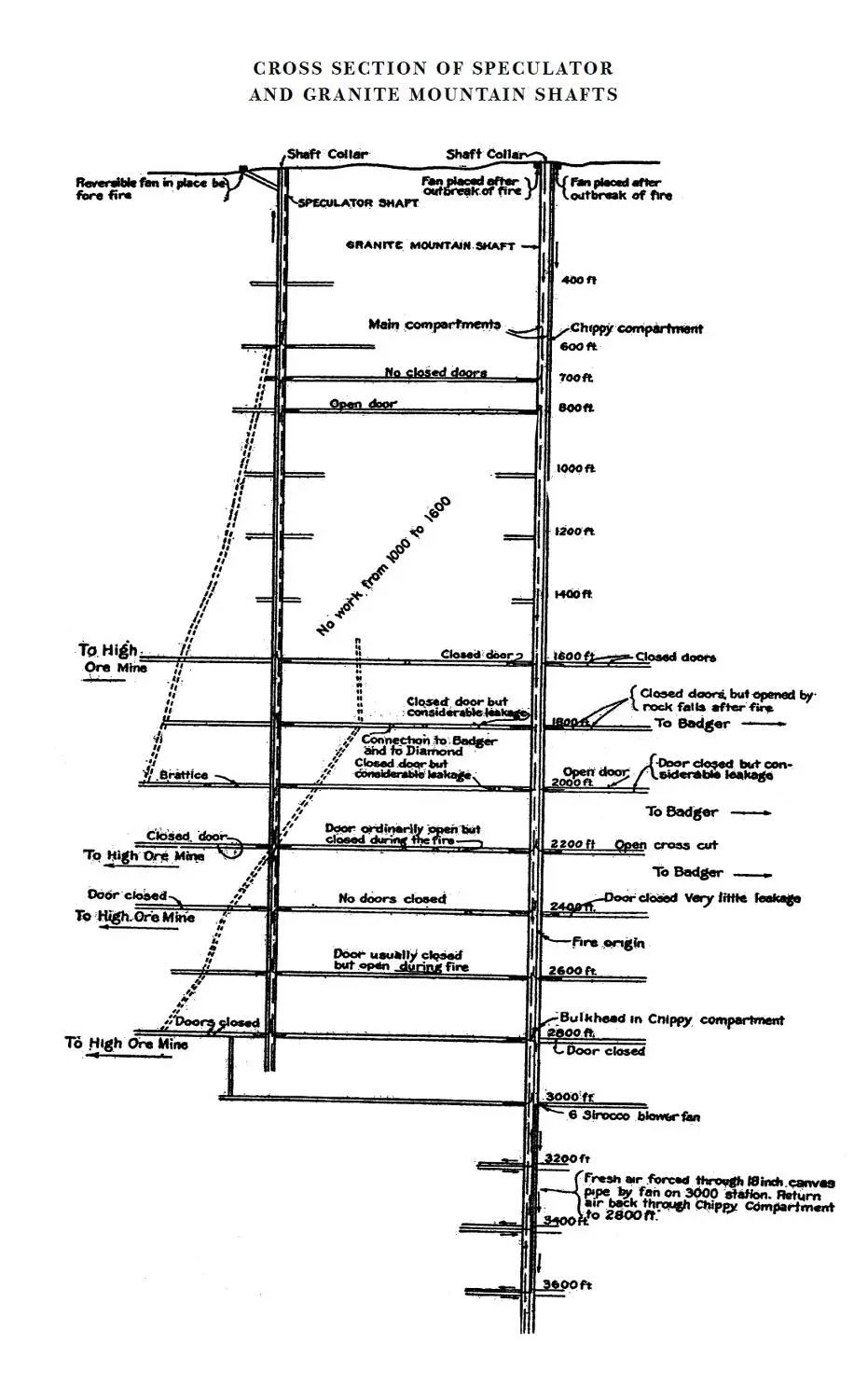

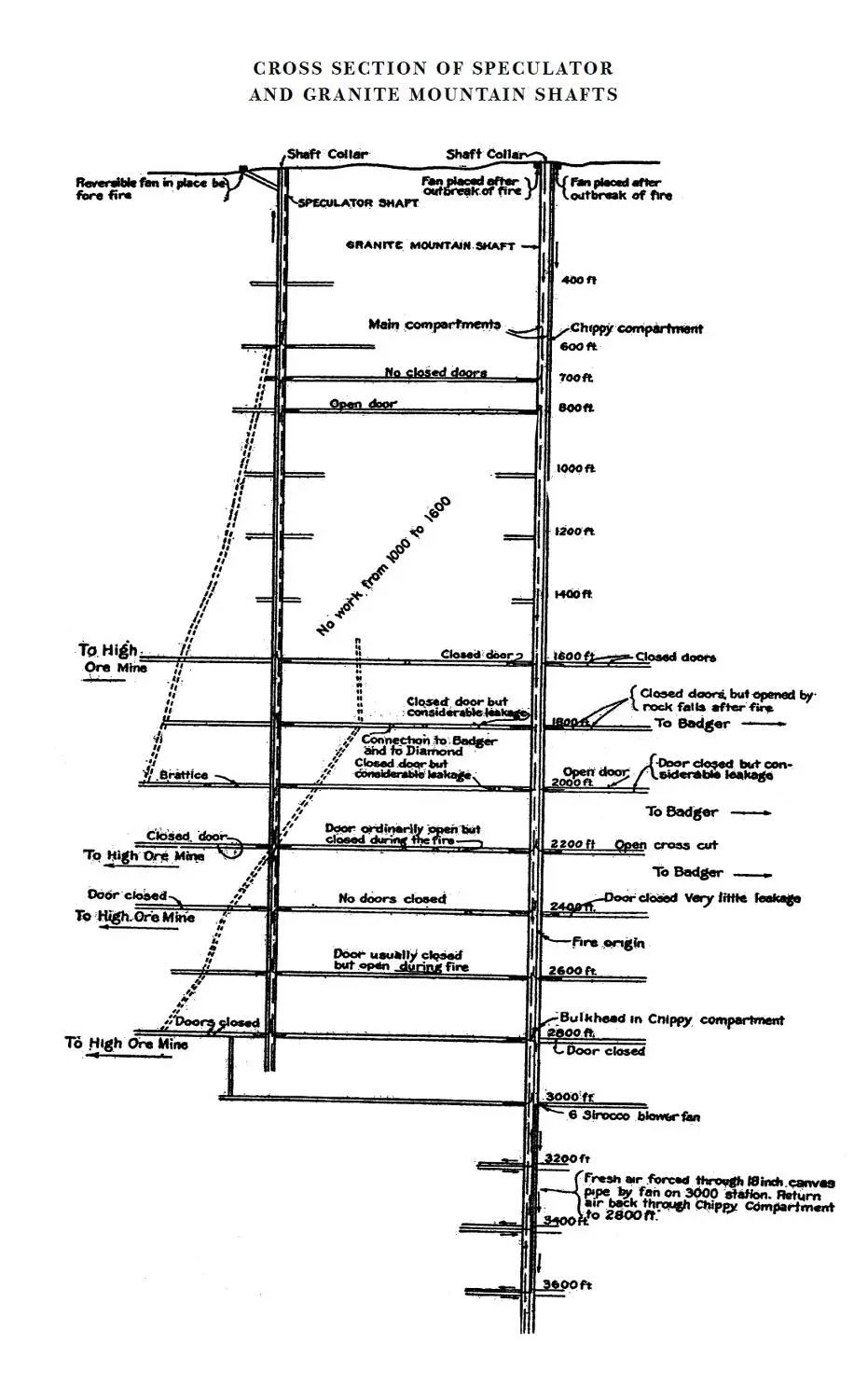

Source for diagram on here:

Bureau of Mines, ‘Lessons from the Granite Mountain Shaft Fire, Butte’, 1922

Copyright © Michael Punke 2006

Michael Punke asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2016

Cover photographs © C. Owen Smithers Collection Butte-Silver Bow Public Archive (front); Shutterstock.com(fire and landscape)

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008189310

Ebook Edition © February 2016 ISBN: 9780008189327

Version: 2016-02-11

Dedicated to the people of Butte, Montana

Tell her we done the best we could, but the cards were against us.

—J.D. MOORE,

JUNE 9, 1917

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

One: “THERE IS A SIGN”

Two : “LIKE A GIGNTIC TORCH”

Three: “THE RICHEST HILL ON EARTH”

Four: “WHAT MEN WILL DO”

Five: “SWEETENED CORRUPTION”

Six: “HELMET MEN BRAVING DEATH”

Seven: “STANDARD OIL COFFINS”

Eight: “THEN WE MET DUGGAN”

Nine: “HEY JACK, WHAT THE HELL”

Ten: “IF THE WORST COMES”

Eleven: “DREADING TO LOOK”

Twelve : “NOW IS THE TIME”

Thirteen: “MEN ALIVE!”

Fourteen: “BAMBOOZELING OR ABUSE”

Fifteen: “TOO GOOD MINERS”

Sixteen: “ IN THE DARK”

Seventeen: “WE’RE DYING IN HERE”

Eighteen: “POINT OF ERUPTION”

Nineteen: “FOR YOU AND THE CHILD”

Twenty: “DUPES AND CATSPAWS”

Twenty-one: “OTHERS TAKE NOTICE”

Twenty-two: “SPY FEVER”

Twenty-three: “WHAT WILL BECOME OF THEM”

Twenty-four: “SOME LITTLE BODY OF MEN”

Twenty-five: “DOWN DEEP”

Epilogue: “NORMAL FOR ITS TIME”

Notes

Index

Acknowledgments

Also by Michael Punke

About the Author

About the Publisher

There is a sign that appears to point persistently to a terrible explosion underground.

—HOROSCOPE PRINTED IN THE ANACONDA STANDARD , JUNE 5, 1917

Butte, Montana, was still dark when the cable crew arrived at the Granite Mountain shaft in the early morning hours of Friday, June 8, 1917. The men could see their breath as they worked in the cold, open air beneath the headframe—a hulking, eight-story steel structure that supported the massive weight of the hoists. The miners called it a “gallows frame” because it looked like a gigantic industrial version of the Old West hangman’s platform. Gallows frames dotted the sprawling hillside like Butte’s version of trees.

The official accident report does not list the names of the men on the crew that morning, but it is a good bet they were a motley mix—the no smoking signs that hung around the mine shaft were printed in sixteen languages. The report does provide the men’s job titles, titles that reflect the task before them: “four electricians, three rope-men, two shaft-men, and one hoist-man.” 1

The worst hard-rock mining disaster in American history began, ironically, as an effort to improve the safety of the Granite Mountain shaft. Granite Mountain, along with its sister shaft, the Speculator, were owned by the North Butte Mining Company. The two mines were rarities—productive Butte properties not owned by the omnipotent Anaconda Copper Mining Company. Anaconda did own all of the properties that surrounded the North Butte holdings. Anaconda, indeed, owned most of the city and a sizable chunk of the state.

By the lax standards of the day, the North Butte Mining Company boasted a considerable reputation for safety. The cable crew’s work on the morning of June 8 was part of an effort to install a sprinkler system up and down Granite Mountain’s 3,700-foot shaft. The shaft was buttressed with chemically treated wooden timbers. In a fire, this highly flammable lining was the functional equivalent of a chimney made of wood. The new sprinkler system, though, was nearly complete. In a week or so, a shaft fire could be doused by simply turning a valve.

One of the few tasks remaining was to relocate a large electrical transformer at the 2,600-foot Station. “Stations” were cavernous openings at hundred-foot intervals and were the junctions between the main shaft and the hundreds of tunnels that branched out from it. The 2,600 Station, therefore, was 2,600 feet below the surface, or “collar,” of the shaft.

The transformer at the 2,600 Station stood only fifty feet from the wood-timbered shaft. Worried that an electrical fire could easily spread, mine officials had decided to move the transformer to a safer location—deeper inside the workings of the mine and well away from the main shaft. The electrical cable that connected it to the surface, however, was too short. The job assigned to the crew was to lower a long cable that could reach the transformer’s new location.

In the era before plastic, electrical wire was commonly insulated with oil-soaked cloth, usually cambric or jute. In industrial settings such as a mine, the cloth was then sheathed in lead for protection. The new 1,200-foot electrical cable being lowered into Granite Mountain was a full five inches in diameter and weighed five pounds per foot, putting its total mass at a staggering three tons.

The narrow five-by-sixteen-foot main shaft contained three hoists—side-by-side elevator cages that could be operated independently of one another. The cages were controlled by a “hoist-man” on the surface. Two of the hoists were dedicated to pulling up lodes of copper ore from the depths of the mine. The other cage, called a “chippy,” was used to transport men and materials. The men in the shaft’s various stations communicated with the hoist-man through a complicated system of electric-powered bell signals.

Читать дальше