Chloë laughed. ‘You don’t need to say Hayward, Mummy. He knows what his own surname is.’

‘Charlotte!’ I called.

Our voices sounded strange, mostly because we didn’t know what we were doing or why we were doing it. Chloë looked at me and almost giggled but then checked herself. Her face went solemn and she listened. I listened as well. The house listened. Someone else seemed to listen too, but I still don’t know who it was. Maybe it wasn’t anyone. Maybe it was just the sense of the strong, clean lines of the present bending for a moment, going shaky and blurred. Whatever it was, for a few uneasy seconds I felt surrounded – not by people perhaps, so much as by moments, lost moments. Forgotten days and nights, lost hours, old minutes that had ticked away and would not come again.

Chloë shuddered, but it was a shudder of excitement.

‘Hmm. I liked that,’ she told me in her precise, Chloëish way. ‘Do you think they heard?’

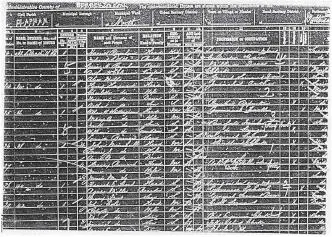

‘Do you know what a census is?’

Later, putting the clothes away in his drawers, I found her older brother Jake, playing Super Mario Tennis.

‘I found out something good about our house today,’ I told him.

He rolled his eyes to show he’d heard, but kept them on the screen. Two grubby thumbs continued to work the control.

I touched his head then bent to kiss his hair. It smelled of boy – a heady combination of old jumpers and school dinners.

‘Do you want to know what it is?’ I said.

Still holding the control, he turned round. On the screen two blue men froze their less-than-friendly poses.

‘Do you know what a census is?’ I asked him.

He sighed and his eyes flicked back to the screen. ‘We did them at school. I know everything there is to know about them.’

‘Well, today I looked up our house on the 1881 census and guess who lived here?’

He put down the control and waited. ‘Who?’

‘A writer called Henry Hayward and his wife and three children – who in 1881 were exactly the same ages as you three are now!’

He shrugged. ‘Great.’

‘A family just like us,’ I told him. ‘Don’t you think that’s extraordinary?’

He seemed to think about this. ‘No.’

‘Come on, you’ve got to admit it’s a bit funny –’

‘How do you know they were like us?’

‘I don’t. But they sound like us.’

He sighed. ‘What were the kids called?’

‘Arthur and Florence and Frank.’

‘It’s sad,’ he said then. I asked him why. ‘I don’t know,’ he said. ‘Would any of them have slept in my room?’ He looked worried. He didn’t want anyone in his space – he hadn’t been keen when we did a house swap with New Yorkers two summers ago. A Victorian child pushing its spectral way in would be the last straw.

‘I don’t know. Yes, I expect so – they must have done.’

He picked up his control again. ‘Look, Mummy, I don’t mean this in a nasty way, but if you find anything else out, could you please not tell me?’

And then this happened. Two months later, on Boxing Day, in the odd, no man’s land that stretches from Christmas to New Year, we suddenly found ourselves with nothing to do. No one had invited us anywhere, we’d made no plans, we had no work to finish.

I found myself pacing up and down our hall in the fading light after lunch, a cardigan tossed over my shoulders and realizing something fatal, if only because I knew that now I would never be able to unrealize it.

‘It’s the wrong colour,’ I told Jonathan finally, ‘the hall and stairwell. Right to the top. I don’t know how I could have ever thought dark turquoise. All this time, I knew there was something. It’s just – well, I’m sorry but my heart always sinks when I walk in the door and now I know why.’

He was reading on the sofa. Or trying to. I snapped the uplighter on and he narrowed his eyes at me. He reminded me that he’d already painted the whole hall and stairwell twice (‘because you decided the lilac was a mistake too’) and asked me what day my period was due.

I threw myself down in an armchair. The whole room felt dark, oppressive. We’d painted it a chic, pale grey more than a dozen years ago, back when I was pregnant with Chloë. It was the winter that Thatcher went. I remember the joy of varnishing the bare boards on my hands and knees one winter’s day, the baby a fluid weight beneath me, while listening to the news on Radio 4. Every minute seemed to bring a fresh excitement.

Back then the dove grey walls had seemed grown-up, calming. Now they just looked drab. I thought I wouldn’t mind changing the colour of this room too. But I knew better than to say so.

‘OK,’ I told Jonathan, ‘you’re right. Forget it. The hall’s fine.’

He shut his book, calmly noting the page number. ‘I didn’t mean it like that.’

‘Three weeks. My period’s due in three weeks – OK?’

‘Three weeks?’ He looked suspicious.

‘I am definitely not pre-menstrual.’

‘What colour would you want it?’ he said.

‘I don’t know.’ I looked at him. ‘Pink?’

Raphael looked up from where he was sitting on the floor sticking football stickers in a shiny album. ‘I’m not living in a gay house.’

‘Blue’s fine, Mummy,’ said Chloë. ‘Relax. It’s just your hormones.’

‘The only way it would be worth doing,’ said Jonathan, who always warms to my plans in the end, ‘would be if we did it properly this time. That means stripping every single scrap of wallpaper off and then replastering and making good. No short cuts. Get a nice clean finish.’

I smiled. Because he likes his nice clean finishes. I’m not saying he’s wrong; it’s just that I will always sacrifice a nice clean finish for something more rapid and exciting – the instant, vivid gratification of a pot of paint slapped on a wall.

He saw my smile. ‘It would mean a lot of work,’ he warned. ‘You couldn’t rush it. We’re talking serious effort. Weeks of work.’

I smiled again.

‘The finish has always bothered me, actually,’ he said.

‘OK.’ I went and got a scraper from the cellar.

‘What are you doing?’

‘Starting.’

‘Now?’

‘Of course now. Why not now?’

‘You are a crazy woman. I don’t know why I live with you. You need the steamer anyway.’

He sighed and got up off the sofa. ‘I’ll get it. And the dust sheets.’

And that’s how we ended up undressing the very old lady that is our house. One dark, aimless Boxing Day, we started stripping her down to her most private, underneath self.

It was three o’clock, almost dark. It felt strangely moving and intimate, scraping the layers off – history unpeeling itself. There was a smell of dissolving paper, of oldness – the hiss of the steamer in the silence, the sight of naked walls. Even patches of mauveish, higgledy Victorian brick in some places where the plaster fell away in large, crumbling, worrying chunks.

‘Oh gross,’ breathed Chloë. ‘What’s all that hair?’

‘Horsehair,’ Jonathan said. ‘They used it to bind the plaster together.’

The odour was odd and sour. The kids fought over who did the scraping but, at thirteen, Jake was the only one who really had the strength to get much off. The light was fading so fast that Jonathan set up an Anglepoise so we could see what we were doing. A circle of white illumination in the misty gloom. It felt magnificent and formal, more like an archaeological operation than DIY.

And the layers of paper curled and rolled off and dropped onto the floor – and, quite perfectly preserved, half a dozen different patterns were revealed: imitation wood grain (the sixties?), brown zigzags (the fifties?) – then a bold Art Deco style in cobalt and scarlet (the twenties?). Under that, large Morris-style chocolate ferns and flowers, and beneath that a solid layer of thick custard-coloured paint, then a fuzzy snatch of long-ago roses, then another more satiny paper with tiny gold and mauve squares. Each layer – imperfectly glued, faded, merged – revealed another.

Читать дальше