GUY CARLETON, FIRST BARON DORCHESTER (1724–1808)

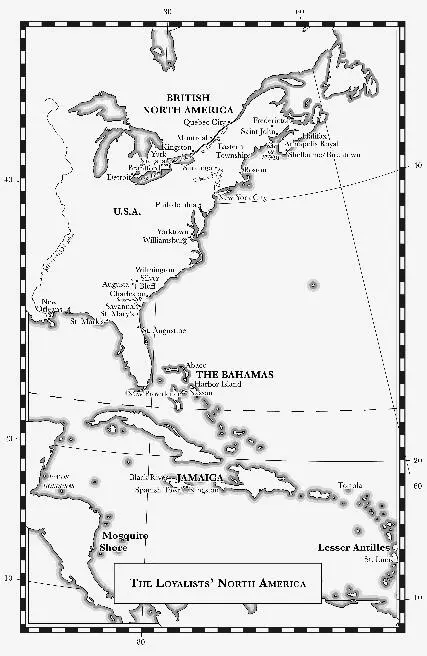

A career soldier, the Anglo-Irish Carleton joined the army in 1742 and assisted in the 1759 capture of Quebec, a place he would remain involved with for almost forty years. Carleton served as governor of Quebec from 1766 to 1778, and is best known for his role in authoring the 1774 Quebec Act. Loyalists knew Carleton best, however, in his position as commander in chief of British forces from 1782 to 1783, in which capacity he superintended the evacuations of British-held cities and helped organize the loyalist exodus. Carleton returned to Quebec as governor in chief of British North America in 1786 (and newly ennobled as Lord Dorchester). Though beloved by loyalists, Dorchester found himself at odds with developments in British imperial policy enshrined in the 1791 Canada Act. As at other points in his career, Dorchester clashed repeatedly with his colleagues, and resigned his position in chagrin in 1794. He retired to England in 1796 and lived in comfort as a country squire. His younger brother thomas carleton (ca. 1735–1817) was governor of New Brunswick from 1784 to 1817, though from 1803 until his death he governed in absentia from England.

GEORGE LIELE (ca. 1750–1820)

Liele grew up in Georgia as a slave. He was baptized in 1772 and became an itinerant Baptist preacher, serving as a spiritual mentor to David George. Liele was granted freedom by his loyalist master and spent much of the war in British-occupied Savannah. He there baptized Andrew Bryan, who went on to found the First African Baptist Church in Savannah. On the evacuation of Savannah in 1782, Liele traveled to Jamaica as an indentured servant to loyalist planter Moses Kirkland. He established the island’s first Baptist church in Kingston, but during the 1790s became the subject of increasing persecution for his religious activities. After a charge of sedition failed to stick, Liele was imprisoned for three years for debt. Though he continued to be active in a range of commercial ventures, he never returned to public preaching after 1800, and his last years remain obscure.

JOHN CRUDEN (1754–1787)

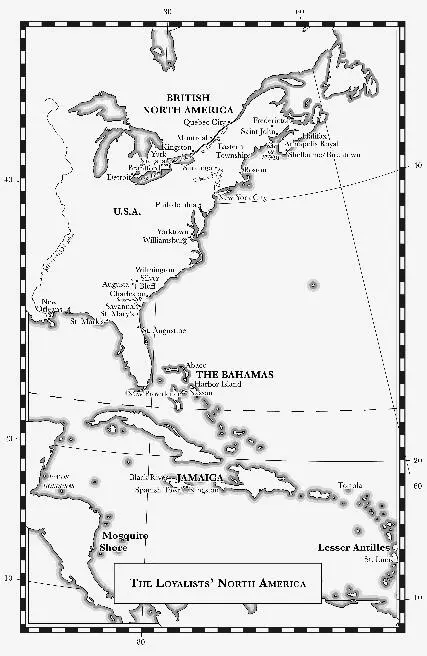

Cruden emigrated from Scotland to Wilmington, North Carolina, sometime before 1770, where he joined his uncle (and namesake) in the trading firm of John Cruden and Company. During the war, Cruden served in a loyalist regiment and was appointed commissioner of sequestered estates in Charleston in 1780, which required him to manage numerous patriot-owned plantations and a labor force of several thousand slaves to produce supplies for the British military and for commercial sale. After Charleston was evacuated Cruden moved to East Florida, where he attempted to block the province’s cession to Spain. In 1785, like many East Florida refugees, Cruden immigrated to the Bahamas, where he lived with his uncle on the island of Exuma. He continued to promote plans for the renewal of the British American empire. Cruden died, insane, in the Bahamas in 1787.

WILLIAM AUGUSTUS BOWLES (1763–1805)

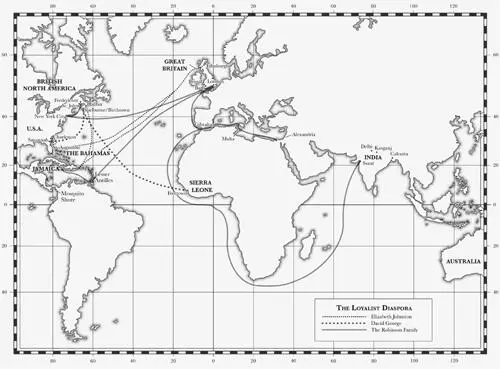

Bowles was the most flamboyant loyalist adventurer of his period. He joined a loyalist regiment in 1777 but deserted in 1779 to settle with the Creek Indians. He married the daughter of a Creek chief and spent several years living in her village. After the revolution, Bowles began plotting to unseat political and commercial rivals in Creek country (which had become part of Spanish Florida). He was supported in these aims by Lord Dunmore and various other imperial officials. A first foray into Florida in 1788 ended in fiasco. A second, more ambitious expedition in 1791 brought Bowles closer to his dream of founding a pro-British Creek state, called Muskogee—but he was captured by the Spanish in 1792 and imprisoned in Havana, Cádiz, and the Philippines in turn. In 1798 Bowles escaped, via Sierra Leone, and returned to Florida for a final effort to establish Muskogee. Though this was the most successful bid of all—he built a capital in 1800 near present-day Tallahassee and presided over his domain for several years—he was betrayed in 1803 by Creeks under U.S. influence. He died in Havana, a Spanish prisoner, in 1805.

SUPPORTING FIGURES

Thirteen Colonies

Thomas Brown, loyalist commander, superintendent of Indian affairs.

Joseph Galloway, advocate of imperial union and loyalist lobbyist.

Charles Inglis, clergyman, loyalist pamphleteer, later bishop of Nova Scotia.

William Franklin, son of Benjamin Franklin, former governor of Pennsylvania, loyalist organizer.

William Smith, chief justice of New York and later Quebec, confidant of Sir Guy Carleton.

Patrick Tonyn, governor of East Florida, 1774–85.

Britain

Samuel Shoemaker, Pennsylvania refugee and friend of painter Benjamin West.

John Eardley Wilmot, MP and loyalist claims commissioner.

Isaac Low, former New York congressman and merchant.

Granville Sharp, abolitionist and sponsor of Sierra Leone settlement.

Nova Scotia

Jacob Bailey, clergyman and author.

John Parr, governor of Nova Scotia, 1782–91.

Benjamin Marston, surveyor of Shelburne.

Boston King, black loyalist carpenter.

“Daddy” Moses Wilkinson, black Methodist preacher.

New Brunswick and Quebec

Edward Winslow, lobbyist for creation of New Brunswick.

Frederick Haldimand, governor of Quebec, 1777–85.

John Graves Simcoe, governor of Upper Canada, 1791–98.

The Bahamas

John Maxwell, governor of the Bahamas, 1780–85 (active).

John Wells, printer and critic of government.

William Wylly, solicitor-general and opponent of Lord Dunmore.

Jamaica

Louisa Wells Aikman, member of loyalist printer family.

Maria Skinner Nugent, diarist, governor’s wife.

Sierra Leone

Thomas Peters, Black Pioneer veteran, leader of resettlement project.

John Clarkson, organizer of loyalist migration, superintendent of Freetown, 1791–92.

Zacharay Macaulay, governor of Sierra Leone, 1794–99.

India

David Ochterlony, East India Company general, conqueror of Nepal.

William Linnaeus Gardner, military adventurer.

Introduction

The Spirit of 1783

THERE WERE TWO SIDES in the American Revolution—but only one was on display early in the afternoon of November 25, 1783, when General George Washington rode on a grey horse into New York City. By his side trotted the governor of New York, flanked by an escort of mounted guards. Portly general Henry Knox followed close behind, leading officers of the Continental Army eight abreast down the Bowery. Long lines of civilians trailed after them, some on horseback, others on foot, wearing black-and-white cockades and sprigs of laurel in their hats. 1Hundreds crammed into the streets to watch as the choreographed procession made its way down to the Battery, at Manhattan’s southern tip. Since 1776, through seven long years of war and peace negotiations, New York had been occupied by the British army. Today, the British were going. A cannon shot at 1 p.m. sounded the departure of the last British troops from their posts. They marched to the docks, clambered into longboats, and rowed out to the transports waiting in the harbor. The British occupation of the United States was officially over. 2

George Washington’s triumphal entrance into New York City was the closest thing the winners of the American Revolution ever had to a victory parade. For a week, patriots celebrated the evacuation with feasts, bonfires, illuminations, and the biggest fireworks display ever staged in North America. 3At Fraunces’s Tavern, Washington and his friends drank rounds of toasts late into the night. To the United States of America! To America’s European allies, France and Spain! To the American “Heroes, who have fallen for our Freedom”! “May America be an Assylum to the persecuted of the Earth!” 4A few days later one newspaper printed an anecdote about a brief shore visit made by a British officer. Convinced that New York would be racked by unrest following the transfer of power, the officer was surprised to find “that every thing in the city was civil and tranquil, no mobs—no riots—no disorders.” “These Americans,” he marveled, “are a curious original people, they know how to govern themselves, but nobody else can govern them. ” 5Generations of New Yorkers commemorated November 25 as “Evacuation Day”—an anniversary that was later folded into the more enduring November celebration of American national togetherness, Thanksgiving Day. 6

Читать дальше