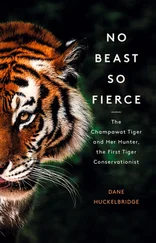

There is, however, a second means of attack that the tiger employs when it regards something not as a threat, but as a potential food source—one that relies less on claws than it does upon teeth. Specifically, a set of three- to four-inch canine teeth, the largest of any living felid (yes, saber-toothed tigers are excluded), designed to sever spinal cords, lacerate tracheas, and bore holes in skulls that go straight to the brain. And it makes sense a tiger would have such sizable canines given their usual choice of prey: large-bodied ungulates like water buffalo, deer, and wild boar. Two of the Bengal tiger’s preferred prey species—the sambar deer and the gaur bison—can weigh as much as a thousand pounds and three thousand pounds, respectively, which gives some idea of why the tiger’s oversized set of fangs are so crucial to its survival. They are the most important tools at its disposal for bringing down some of the most powerful horned animals in the world. To crush the muscle-bound throat of a one-ton wild forest buffalo is no easy task, but it is one for which the tiger is purpose-made.

The tiger’s evolutionary history, however, begins not with a saber-toothed gargantuan eviscerating lumbering mastodons, but with a diminutive weasel-like creature scampering among the tree branches. With miacids, more specifically, primitive carnivores that inhabited the forests of Europe and Asia some 62 million years ago. Bushy-tailed and short-legged, these prehistoric scamps lived primarily on an uninspiring diet of insects. Their bug-feast would apparently continue for another 40 million years, until the fickle tenants of evolutionary biology put a fork in the road—some miacids evolved into canids, which today include dogs, wolves, foxes, and the like, while a second group, over the eons that followed, would turn into felids, or cats. Initially, there were three subgroups of felids: those that could be categorized as Pantherinae, Felinae, and Machairodontinae, with the third, although today extinct, including saber-toothed Smilodons that were indeed capable of ripping the guts out of woolly mammoths, thanks to their foot-long fangs and thousand-pound bodies.

Tigers, however, arose from the first group. Unlike leopards and lions, which both came to Asia via Africa (there are still leopards in India today, as well as lions, although only very small populations survive in the forests of Gir National Park), tigers are truly Asian in origin, first appearing some 2 million years ago in what is today Siberia and northern China. From this striped ancestor, nine subspecies would emerge, to spread and propagate across the continent, of which six still survive today, albeit precariously.

The Bali tiger, the Javan tiger, and the Caspian tiger all went extinct in the twentieth century, due to the usual culprits of habitat destruction and over-hunting. The first vanished from the face of the earth in the early nineteen hundreds, although the latter two subspecies seemed to have hung on at least until the 1970s. The extermination of the Caspian tiger is especially unsettling given the sheer size of its range—the large cats once roamed from the mountains of Iran and Turkey all the way east to Russia and China.

Of the tiger subspecies that still exist today, the Amur tiger—also known as the Siberian tiger—has stayed closest to its ancestral homeland in the Russian taiga, and continues to prowl the boreal forests of the region in search of prey. This usually means boar and deer, although at least one radio-collared tiger studied by the Wildlife Conservation Society, or WCS, was recorded as feasting primarily on bears. It seems the Amur not only has a preferred method of killing bears, involving a yank to the chin accompanied by a bite to the spine, but that it is also somewhat finicky, preferring to dine on the fatty parts of the bear’s hams and groin. With a thick coat, high fat reserves, and pale coloration, the Amur tiger is well suited to the wintry landscape of the Russian Far East. It is generally considered the largest of all the tiger subspecies, with historical records showing weights of up to seven hundred pounds, although a modern comparison of dimensions reveals that Bengal tigers in northern India and Nepal today are actually larger on average than their post-Soviet relatives farther east. Research hasn’t effectively concluded why Amur tigers are physically smaller today than in centuries past, although the removal from the gene pool of large “trophy” tigers could well be a factor. The Amur tiger’s current wild population numbers only in the hundreds, confined to a few pockets of eastern Russia and the borderlands of China.

While the northernmost realms of East Asia are prowled by what little remains of the Amur tiger population, the warmer climes to the south claim their own small subgroups of Panthera tigris, in the form of the Indochinese tiger, the Malayan tiger, the Sumatran tiger, and the South China tiger. All of their populations are atrociously small, with the South China tiger bearing the ignominious distinction of being categorized, at least recently, as one of the ten most endangered animals in the world, and quite possibly extinct in the wild. The future of all tigers is precarious at best, but in the case of these lithe jungle dwellers, considerably smaller on average than their brethren to the north, it is even more so.

Farther west, however, in the forests of India, Nepal, Bhutan, and Bangladesh, there is another tiger yet, and although endangered, it has miraculously managed to maintain numbers that border on the thousands. It is the tiger of Mughal emperors and maharajas, of Rudyard Kipling and William Blake. The tiger that Durga, the Hindu mother goddess, rode into battle to vanquish demons, and that the rebellious Tipu Sultan—also known as the Tiger of Mysore—chose as his standard. It is the tiger that yanked British generals from their howdahs atop elephants, that turned entire villages in Bhiwapur into ghost towns, and that is responsible for the vast majority of the million people believed to have been killed by tigers over the last four centuries. It is the tiger of nursery rhymes, the tiger of nightmares, the tiger our imagination conjures when the word itself is spoken. It is identified by scientists, rather prosaically if not redundantly, as Panthera tigris tigris, but it is known to all as the Bengal tiger.

There is no shortage of shades or strokes one can employ when it comes to painting a portrait of the Bengal tiger, but to begin: Bengal tigers are big . While females tend to max out close to 400 pounds, adult males regularly achieve body weights in excess of 500 pounds, and some exceptionally large individuals have been documented at weights of over 700 pounds. Royal Bengal tigers, the subset that lives in the sub-Himalayan jungle belt known as the terai, tend to be even bigger. One extraordinary specimen—reportedly also a man-eater, at least until David Hasinger shot it in 1967—weighed in at 857 pounds, measured over 11 feet long, and left paw prints “as large as dinner plates.” For its last supper, it managed to drag not only a live water buffalo into the forest, but also the eighty-pound rock to which it was tethered. The humongous tiger’s man-and-water-buffalo-eating days may have ended shortly thereafter, but it still prowls today—in the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History, in fact, where it is on permanent display in the Hall of Mammals.

Second: Bengal tigers are fast . In short sprints, they can achieve forty miles per hour, which is almost three times as fast as the average human being, and roughly equivalent to the top speed of a Thoroughbred racehorse. In other words, it is futile to try to outrun a dedicated tiger. And when it comes to their leaping prowess, there are plenty of examples of tigers clearing tremendous hurdles to get their claws on a target. In an incident recorded in Nepal in 1974, a startled tigress protecting her cubs had little trouble mauling a researcher hiding fifteen feet above her in a tree. The aforementioned tiger from Kaziranga National Park managed in 2004 to take three fingers off that unfortunate elephant driver’s hand—a hand that appears to be at least twelve feet off the ground—with barely a running start. And on Christmas Day, 2007, a tiger (Amur, not Bengal, although their abilities are comparable) escaped the ostensibly inescapable barriers of its open-air enclosure at the San Francisco Zoo, for the sole purpose of going after a trio of young men who had provoked its ire. Accounts vary as to what caused the attack—the zoo accused the victims, all of whom had alcohol and marijuana in their systems, of taunting and harassing the animal, something the two survivors vigorously denied. What is certain, however, is that the enraged tiger got across a thirty-three-foot dry moat, cleared a nearly thirteen-foot protective wall, and emerged snarling from the pit like the wrath of God. Police arrived in time to save two of the young men from almost certain death—the third, who received the brunt of the initial attack, was not so lucky—but stopping the crazed tiger proved anything but easy. One officer fired three .40-caliber-pistol rounds into the charging cat’s head and chest, and that only seemed to anger it further. It wasn’t until a second officer put a fourth bullet in the tiger’s skull at point-blank range that it finally ceased its attack and fell to the ground. A more nightmarish scenario is difficult to imagine, but it is at least worth mentioning—this was only a captive tiger. Experienced wild tigers, accustomed to bringing down big game and fighting off territorial rivals, are generally much more athletic and aggressive when their hunting or defensive instincts kick in. A tiger in its natural habitat—alert, attuned, muscles rippling beneath its tawny striped hide—is another creature entirely from the languid, yawning pets of Siegfried & Roy. As lethal as this urbanized West Coast zoo tiger proved to be, it was a flabby house cat compared to its country cousins, ripping apart wolves and chasing down bears in ancient forests across the sea.

Читать дальше