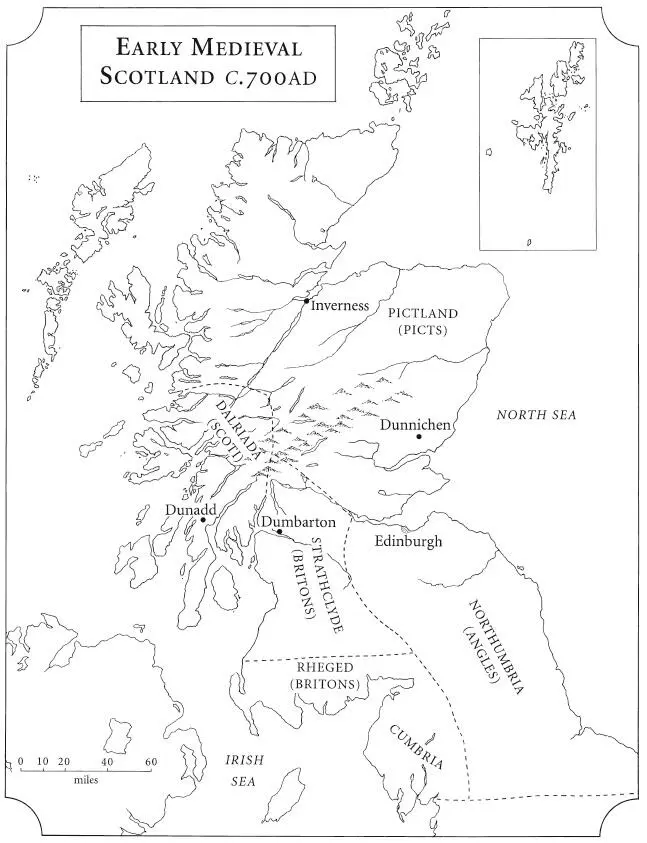

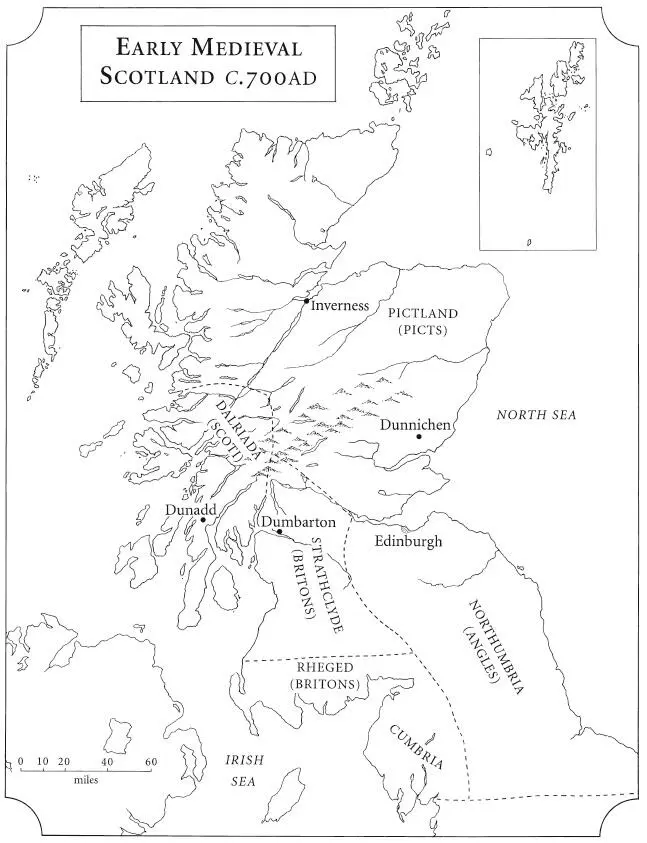

The massive natural fortress of Dunadd, in mid-Argyll, rears out of the Crinan Moss (Moine Mhor – the ‘great moss’) at the southern end of the fertile Kilmartin Glen above Lochgilphead. For historical pilgrims intent on getting a ‘feel’ for ancient Dalriada, there is a new Museum and Visitor Centre (Kilmartin House) in the village of Kilmartin at the head of the valley. 2

The hill-fort of Dunadd is only one of the many power-bases of the old kingdom of Dalriada, but it is perhaps the most striking and evocative. It stands back from the A816 from Lochgilphead to Oban, fifty-four metres high, a grass-grown rock mass made of epidiorite schist and shaped by glacial action – what geologists call a roche moutonnée. It is a bit of a scramble in places to reach the top, through natural clefts in the rock, but there is a wonderful panoramic view from the summit which makes the effort well worth while.

The steep zigzag route to the summit leads through two defiles which give access to concentric terraces which girdle it. The terraces are buttressed by the living rock, and any gaps were filled in by walling to complete the defences. The terraces provided space for timber structures, no trace of which now remains. The path leads onwards and upwards to the highest of the terraces, just below the sanctuary of the summit. On this grassy shelf lies the magnet which draws visitors to the top: a carved footprint incised into the bedrock, pointing more or less directly towards the distant Ben Cruachan, the ‘holy mountain’ of Argyll. There is also a roughly-scratched outline of a boar (a Pictish symbol) and an inscription in the unintelligible alphabet known as ogam. On another rock, just behind the ‘heel’ of the footprint, is a small hollowed-out basin (possibly for libations).

It is a tantalisingly enigmatic spot, where the imagination can take wing. Most commentators now agree that the carved footprint was used in the ritual inauguration of early Dalriadic kings; the new king would have placed one foot in the carving during the ceremony, in full view of his people gathered on the terrace below, to symbolise a royal ‘marriage’ with the land. Today’s visitors cannot resist trying the fit for themselves. 1

There is a magic resonance about Dunadd; for the people of Argyll it is the birthplace of the Scottish nation, a royal centre of major importance in the growth of ‘Scotland’ as a coherent realm. It has an overwhelming sense of place, of belonging to the land, superintending the surrounding countryside: the coiling meanders of the River Add below, Kilmartin Glen to the north, the hills of Knapdale to the south and, to the west, the Crinan Estuary and the Sound of Jura marking the route of the incomers from Antrim.

Recent archaeological excavations have shown that Dunadd was occupied, albeit intermittently, from about AD 500 to 1000; it is usually called ‘the capital’ – or ‘ a capital’ – of the kings of Dalriada. It was a place where skilled craftspeople fashioned high-quality jewellery and implements in bronze, silver and gold. It was also a major trading centre in a huge Celtic network which stretched from Ireland, down the west coast of Britain and across to the Mediterranean. Dunadd was clearly an important player in European trade, exporting commodities like hides, leather and metal-work and importing luxury goods from abroad. One of the most intriguing items found during excavations at Dunadd was a small piece of a yellow mineral named orpiment which comes from the Mediterranean; orpiment is the mineral which produced the beautiful golden yellow ink used by medieval scribes for their illuminated manuscripts, and may have been used on Iona to make the Book of Kells. Adomnán, the biographer of St Columba, described a visit paid by Columba to the caput regionis (capital of the region) and his talking to sailors from Gaul – perhaps he was there to buy orpiment for his scriptorium on Iona!

Ted Cowan, Professor of Scottish History at Glasgow University, says of the carved footprint on Dunadd:

The new king of Dalriada metaphorically (and almost literally) stepped into the shoes of the old king – it’s a perfect size nine shoe, by the way. It carried overtones of fitting the role of being king, of being the only person whose foot fitted the footprint; the last echo of that concept is heard in the story of Cinderella and the glass slipper – the Ugly Sisters try it on, but Cinderella, the ‘real’ princess, is the only person whose foot fits.

These inaugurations would have been Christian ceremonies, whatever ancient pagan traditions may have been reflected in them. And that brings us to a consideration of the impact of Christianity on early Scotland.

The coming of Christianity

Before the Romans officially declared an end to their occupation of Scotland, in 410, the south-west of Scotland may already have been Christianised; early in the fourth century the Emperor Constantine had declared Christianity to be the official religion of the Roman Empire, and this may have led to the establishment of some kind of ‘sub-Roman Church’ in Pictland.

The Venerable Bede wrote that, after Constantine made Christianity official, ‘faithful Christians who during the time of danger had taken refuge in woods, deserted places and hidden caves, came into the open and rebuilt the ruined churches. Shrines of the martyrs were founded and completed and openly displayed everywhere as tokens of victory. The festivals of the Church were observed, and its rites performed reverently and sincerely.’

The one name which emerges from the scanty sources about south-west Scotland during this period is that of St Ninian. Ninian (Nynia) is the first Christian missionary in Scotland’s history who is known to us by name. Bede called him ‘a most reverend and holy man of British race’, and recorded a tradition that he had been trained in Rome and that his see was at St Martin’s Church at Candida Casa (the ‘White House’), identified as Whithorn in Galloway. He was, apparently, the son of a converted British chieftain, who began his mission in the south-west late in the fifth century as the bishop of a Romanised community which had been Christian for some time. By the seventh century Ninian had become a cult saint, and many churches were dedicated to him in different parts of Scotland in the ensuing centuries.

In the west of Scotland, St Kentigern, or Mungo, 1 founded a church beside the Molindinar Burn; it was in a ‘green hollow’ ( glascu ), which gave the city of Glasgow its name. By 600, Kentigern/Mungo was established as the first bishop of the kingdom of Strathclyde centred on Dumbarton; his shrine lies in the crypt of Glasgow Cathedral.

The man most closely associated with the spread of Christianity in the sixth century, however, is Columba ( Colum Cille , ‘Dove of the Church’, c.521–97). He was a scion of the Uí Néill, the most powerful royal family in Ireland at the time. Columba was a vigorous and hot-blooded warrior-monk who was banished after a particularly bloody battle and, as a penance, chose to lead a mission to the Scoti of Dalriada. In 563 he set sail in a coracle with twelve companions to do God’s work. After some years on an island which Columba called Hinba (perhaps Jura), the king of Dalriada gave him the island of Iona, off the west coast of Mull, probably in the early 570s. Here he founded a large monastic community which was to become the spiritual powerhouse of Christianity in northern Britain. It also became a renowned centre of learning and artistic excellence, and owned an extensive library of books: many claim that the magnificently illustrated Book of Kells, now in the library of Trinity College, Dublin, was produced in a scriptorium on Iona. Columba’s biographer, Adomnán, wrote that he was engaged in making a new manuscript of a psalter on the day of his death.

Читать дальше