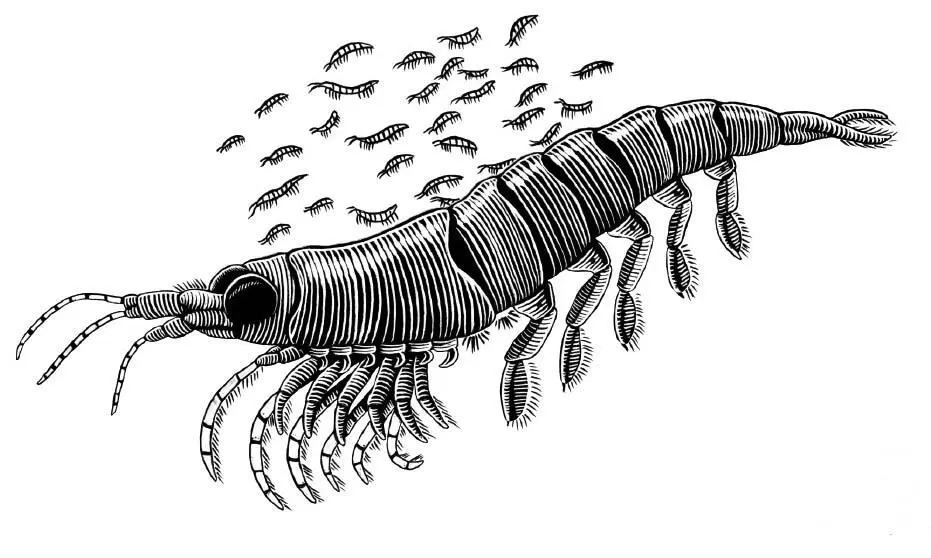

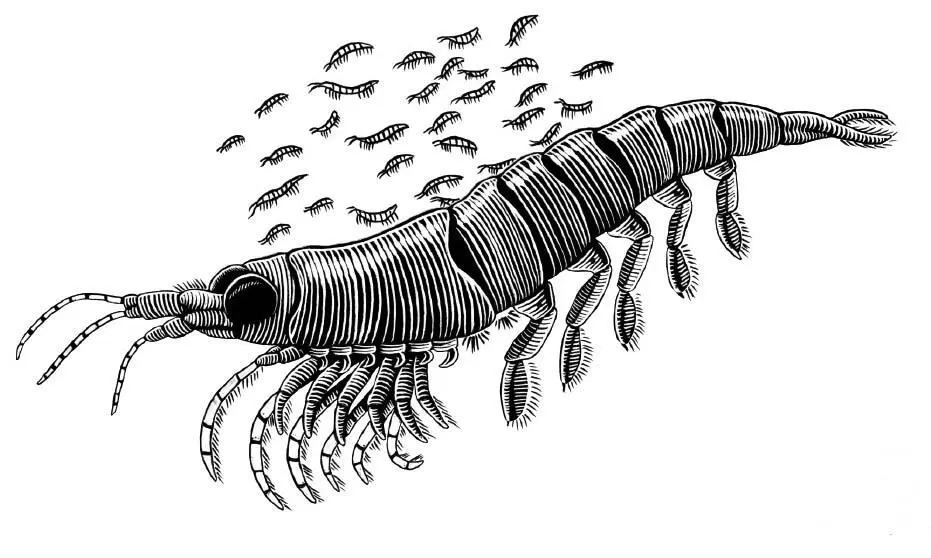

In Wilhelmina Bay our goal was to attach a sleek plastic tag to the back of a whale to record audio, video, depth, changes in the whale’s speed, and even pitch, yaw, and roll. Our tags would provide crucial context for how humpbacks interact with their environment by relaying, in a time-stamped way, how they feed on krill. Ari and his colleagues have tagged and tracked whales along the Antarctic Peninsula for nearly two decades, charting their movements against the backdrop of changes in krill-patch density, water temperature, daylight, and other variables. As climate change warms the poles faster than the rest of the planet, every year counts.

I sat on the gunnel of the boat while Ari scanned from the bow. We were several days into a multiweek expedition with high hopes to tag as many humpbacks as possible—ideally, a pod feeding together—but thus far we had been skunked. Ari stood rigid like a figurehead, holding a twenty-foot-long carbon-fiber pole in folded arms. The pole flexed in synchrony with the swell, the teardrop-shaped tag bobbing at one end. I watched clouds shift slowly overhead, mirroring the dappled quicksilver of the water, and wondered whether any other place on Earth could feel as alien as Antarctica. Then a loud gurgle interrupted my daydreaming, followed by a trumpeting blast of water vapor bursting from flaring, paired nostrils. A whale’s blow.

We knew to expect more plumes of water immediately thereafter. A pod of whales synchronize when they surface to breathe—sometimes nearly simultaneously or split seconds apart. They usually breathe a few times in a row, in quick succession, before resubmerging—unless they’re asleep or truly exhausted, whales tend to act like surfacing is a nuisance and they’d rather be deep underwater. Their tight coordination in breathing likely has a lot to do with maximizing time spent below the surface engaged in the cooperative tasks of finding food and avoiding predators. Some species travel or hunt in pods that are tightly knit family genealogies, while others, such as the humpbacks before us, form short-lived associations, seemingly a matter of happenstance.

“Oh, that’s right,” Ari called out. The vapor from the blow lingered in the cold air. Ari pointed to a small patch of water a dozen yards from the boat, perfectly calm against the waves at the surface. This patch, called a flukeprint, betrayed the whale’s movement, unseen deep below our tiny boat. The single flukeprint bloomed into several, each the size of our boat, rising up from the depths, whirling and spreading into the smooth geometry of a lily pad. We were right. “He’s got buddies,” Ari said. Without the aid of an echo sounder—which would also tip off the whales about our location—we used the ephemeral patterns on the surface to read their path.

We started up the engine, throttling ahead slightly to a spot beyond the last flukeprint. Within seconds, right on cue, a pair of enormous nostrils bubbled at the surface, releasing a thundering tone and then a spray that carried past us as we kept up with the whale. A dorsal fin surfaced, and a second and third blow exploded nearby. “Pull up behind this last one. We have about three more breaths until they go down,” Ari shouted.

We trailed the laggard of the group, maneuvering the boat into position. Ari lowered himself across the bow and held the pole against his torso, extending the tip with the tag just ahead of the dorsal fin as we motored close to the behemoths moving yards away. Then, in a decisive motion, Ari launched the tip of the pole toward the whale’s back, where the tag’s suction cups hit the skin with a satisfying thwack . The whale rolled beneath the surface as we pulled back to pause and wait for it to return. We spotted its sleek, shiny back as it arose again, marked with a neon tag, and we cheered. The whale took one last breath before it raised its monstrously wide tail flukes out of the water and slipped down into emerald darkness with the others. Ari radioed back to the Ortelius . “Taaaaag on,” he said with a hint of swagger as he grinned at me.

Tag on

The whole rodeo of tagging is a bit like sticking a smartphone on the back of a whale, complete with the logistics of getting close enough to a forty-ton mammal in the first place. Just as your smartphone can record movies, track where you go, and automatically rotate images, the same technology—miniaturized and cheap, combining video, GPS, and accelerometers all in one device—has fueled a revolution in understanding how animals move throughout their world. Scientists call this new way of recording organismal movement biologging, and it has captured the interest of ecologists, behavioral biologists, and anatomists, all interested in knowing the details of how animals move through space and over time. Biologging has been especially important for revealing the daily, monthly, and even annual meanderings of animals that are extremely difficult to study. Stick a tag on a penguin, a sea turtle, or a whale, and there’s a chance to know how it swims, what it eats, and everything else it does whenever you’re not around to watch it—which is most of the time, for animals at sea.

The logistics of studying whales places them in a realm truly apart from every other large mammal on land or at sea. To know anything about them in the wild takes time on a boat, sticking a tag on their back, sliding a camera underwater, or spying overhead with a drone—if you’re lucky enough to come upon them in the first place. Biologging is helping us overcome this challenge by giving us a remote view into their lives, an extension of our senses more intimate and sometimes more detailed than any telephoto lens. In the case of humpbacks, tag data have revealed how these gulp-feeding whales lunge at large schools of krill and other prey, oftentimes in coordinated attacks. It’s a form of pack hunting, which might seem strange for a species celebrated as gentle giants. But baleen whales are serious predators, not like grazing cows but more like wolves or lions, pursuing their quarry with strategy and efficacy. Don’t be fooled by their lack of teeth, or just because krill don’t bleat in terror.

Hours later the Ortelius prowled silently through Wilhelmina Bay, with a pair of massive spotlights leading the way in search of icebergs in our path. Outside on the bow, I watched heavy snowflakes drift through the cones of light as Ari unfolded the metal radio antenna that would lead us back to our tag. The tags we were using had to be re-collected to yield their data; we would have to find and physically pluck them out of the water, provided that they’d already been knocked off the whales’ backs. By design, they can last minutes, hours, or even days from the force of suction alone, before being scraped, being bumped, or falling off. Its buoyant neon housing would keep the whole device floating on the surface until we triangulated its position.

Over the course of his career, Ari has probably tagged more species of whales than anyone, in all circumstances and in every ocean. Beyond friendship, mutual colleagues, shared ambitions, and wry humor, we were working together in Antarctica to build a bridge between our disciplines—paleontology for me, ecology for him—because questions about how whales evolved to become masters of ocean ecosystems over fifty-odd million years need to be grounded in the facts of what whales do today. Bridging gaps between disciplines sometimes necessitates spending time side by side. All the better if it’s in the field.

Читать дальше