Nadya’s warmth, as well as her frustration, surfaces in a letter to the aunt of her stepson Yakov, Maria Svanidze, of whom she was clearly very fond. Maria and her husband, Alexander, were then living in Berlin, where he was working for the Soviet Bank for Foreign Trade. Nadya wrote the letter just before the birth of Svetlana, who, despite her mother’s ambivalence about the pregnancy, obviously treasured the letter, translating it into English herself and saving it:

JANUARY 11, 1926

Dear Maroussya

You write that you feel bored. You know, my dear, it’s the same thing everywhere. I have nothing to do with anyone in Moscow. Sometimes that looks even strange: in so many years not to develop close friendships, but that depends on character. It is strange that I feel much closer to non–party members, I mean women. This public is much simpler to get along with.

I regret that I have again took [ sic ] upon myself strong family bonds [here Svetlana added a footnote: “N. S. Allilueva was expecting her daughter Svetlana at that time”]. This is not so easy in our days, because there appeared to be so many new prejudices, like if you are not working you are a “baba,” *although perhaps one does not work only because one does not have due qualifications. And now when I am going to be with family business, it is impossible to think about one’s qualifications. I advise you, dear Maroussya, to obtain some skills for Russia, while you are abroad. I am serious. You simply cannot imagine how unpleasant it is to work simply for earnings, doing any work; one must have a specialty, specialization, which would liberate you from dependence on others. . . .

Well, my dear Maroussya, do not feel lonely, do obtain necessary qualifications and come to us next time. We shall all be very happy to see you. Joseph is asking me to give you his love. He has very good feelings toward you (he says “she is a smart baba ”). Do not get angry—that is his usual way to treat us, women. . . .

I kiss you and goodbye,

Nadya 16

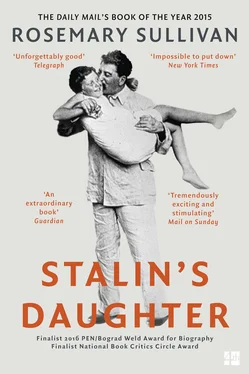

Nadya was fed up with being a shadow in the Kremlin and was determined not to be a baba . As soon as Svetlana was born, Nadya, then twenty-five, searched for a nanny to care for her infant daughter so that she would be free to pursue her own education. After interviewing prospective candidates, she settled on Alexandra Andreevna Bychkova.

Alexandra Andreevna knew about loyalty. She had been born in 1885 on an estate in Ryazan, southeast of Moscow, and worked as maid, cook, nurse, and housekeeper until she joined the Saint Petersburg household of Nikolai Yevreinov, a theater director and critic, a member of the prerevolutionary liberal intelligentsia. The Yevreinov family taught the illiterate Alexandra Andreevna to read and write. When the outbreak of the Revolution forced them to flee to Paris, they invited her to accompany them, but she refused to leave the motherland. During the famines of the early 1920s, she fled, with her one remaining son (the other had died of starvation), to Moscow, where Nadya Stalina discovered and hired her. Svetlana’s adopted brother, Artyom Sergeev, would say that Alexandra Andreevna was “an absolutely wonderful nanny.” She reminded him of Pushkin’s faithful nanny, Arina Rodionova. 17

Alexandra Andreevna was a remarkable storyteller who threaded her conversation with Russian proverbs, filling the children’s ears with tales of her village and of her “theater” days in Saint Petersburg. Her greatest gift was her capacity to keep silent as she weathered all the vicissitudes over the years in the Stalin household. Svetlana would say of her, “For me, during my whole life, she was an example of calmness, hard work, warmth, some kind of epic tranquility, and an unending optimism.” 18

Nadya left Svetlana’s nanny strict instructions never to let her charge be idle. Svetlana remembered her nanny taking her to preschool for music lessons with twenty other children. Svetlana sang in a children’s chorus and was soon taught to read and transcribe music and play the piano. Alexandra Andreevna stayed with Svetlana for thirty years until her death in 1956, serving as nanny for Svetlana’s own children. If there was any ethical grounding for Svetlana in the morally ambiguous Stalin universe, it came from her nanny, Alexandra Andreevna. “If it hadn’t been for the even, steady warmth given off by this large and kindly person,” Svetlana later wrote, “I might long ago have gone out of my mind.” 19

In 1928, when Svetlana was two, Nadya enrolled at the Industrial Academy to study synthetic fibers, a new branch of chemistry. There were also endless Party meetings, and what free time Nadya had she spent with Stalin. She hired tutors to oversee her children’s education, while she was mostly absent.

As Svetlana put it with some resentment, “It was not the thing at that time for a woman, especially a woman Party member, to spend much time with her children.” 20All the Kremlin wives had Party jobs. In their spare time, some took up tennis. There were tennis courts and croquet sets on those dacha lawns. It was an uncanny replication of the old tsarist aristocracy’s way of life.

Nadya hired a German housekeeper from Latvia, Carolina Til, to run the Kremlin apartment and left everything to her German efficiency. She also hired a governess for Svetlana and a male tutor for Vasili, much as the tsars had done. Svetlana learned to read and write German and Russian by the time she was six.

From left: Carolina Til, the housekeeper, and the nanny Alexandra Andreevna Bychkova.

(Svetlana Alliluyeva private collection; courtesy of Chrese Evans)

The life of all the children in the numerous Kremlin apartments followed a similar routine, run by governesses and tutors. But it was not all discipline. Stepan Mikoyan, whose father was an Old Bolshevik and a Soviet statesman, one of the few who survived Stalin’s purges, lived in the Horse Guards building and used to play with Vasili and Svetlana. He remembered afternoons when all of the children of government officials, including the staff—there must have been thirty or forty children—raced through the gardens. Svetlana was a tomboy and fearlessly climbed the Tsar’s Cannon, the largest cannon in the world, just like everybody else. 21

There were rollicking children’s parties at which twenty or thirty children might read a fable by the nineteenth-century writer Ivan Andreyevich Krylov, imitating the animals and wearing actual bearskins. But they would also chant satirical couplets about “political double-dealers.” Their parents would be the audience, and even Stalin might be there, a passive witness, as was his habit, watching indulgently from the sidelines. “Once in a while,” his daughter would remark laconically, “he enjoyed the sounds of children playing.” 22

Svetlana remembered her sixth birthday. The Kremlin flat was full of children. They had prepared songs and dances, and she recited some German poetry. It had been a feast, complete with tea and small cakes in cups. Svetlana had to hold this memory in a sealed compartment since she recognized, years later, that much of the rest of Russia had been starving.

Only once did Svetlana recall spending a full day with her mother. She remembered watching in amazement as Nadya furiously cleaned the underside of the claw-foot bathtub and then the rest of the apartment. She was too young to understand that the motive was probably less her mother’s obsession with cleanliness, though there was that, than a wife’s repressed anger, for there was much unhappiness in the Stalin family. Stalin and Nadya often fought. Years later Polina Molotov, Nadya’s close friend, told Svetlana, “Your father was rough with [your mother] and she had a hard life with him. Everyone knew that. But they’d spent a good many years together. They had a family, children, a home, and everyone loved Nadya.” Although it wasn’t a happy marriage, Polina asked, “What marriage is?” 23

Читать дальше

![John Bruce - The Lettsomian Lectures on Diseases and Disorders of the Heart and Arteries in Middle and Advanced Life [1900-1901]](/books/749387/john-bruce-the-lettsomian-lectures-on-diseases-and-disorders-of-the-heart-and-arteries-in-middle-and-advanced-life-1900-1901-thumb.webp)