Star of the Morning

The Extraordinary Life of

LADY HESTER STANHOPE

KIRSTEN ELLIS

For Michael and Nathanielandthe Stephan sisters, Rania and Wafà

Dayr, the Lion of the Desert, to Hester, the Star of the Morning, sends greeting, with love and service. Those who obey the sabre of Dayr, hold the Great Desert in the hollow of their hand, even as the ring encircles the finger. Warriors without number, horses, camels, powder and shot, what is required … all is ready. You need only to send your orders.

Your true friend, Dayr

DAYR AL FADIL, Bedouin Sheikh of the Anazeh, To Lady Hester Stanhope

If you were a man, Hester, I would send you on the Continent with 60,000 men, and give you carte blanche and I am sure that not one of my plans would fail.

WILLIAM PITT THE YOUNGER, Prime Minister of England

The Arabs have never looked upon me in the light either of man or woman, but un être à part.

HESTER LUCY STANHOPE

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

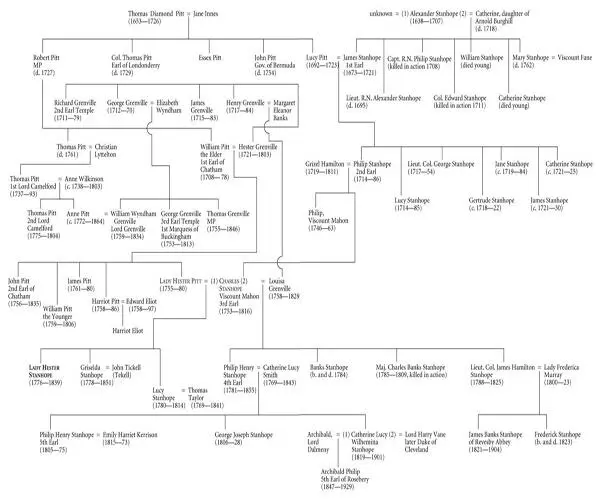

Family Tree

Maps

Prologue

1 Beginnings

2 The Minority of One

3 The Company of Men

4 A Summoning of Strength

5 Love and Escape

6 A Bolt-hole on the Bosphorus

7 Indecision

8 Friendships

9 Under the Minaret

10 The Desert Queen

11 Separation and Despair

12 ‘The Queen Orders Her Minister’

13 A Chained-up Tigress

14 ‘I Will Be No Man’s Agent’

15 The Broken Statue

16 Revenge

17 ‘I Am Done With All Respectability’

18 Mr Kocub’s Spy

19 The Sun At Midnight

20 Djoun

21 The Mahdi’s Bride

22 The Last Dance

Epilogue

Bibliography

Index

Acknowledgements

Notes

Copyright

About the Publisher

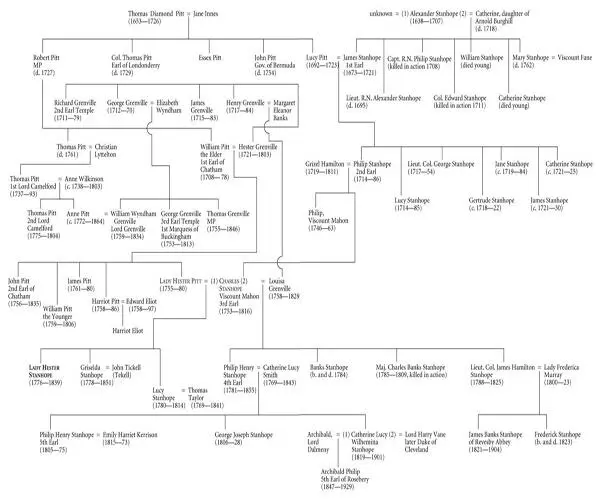

Lady Hester Stanhope’s Family Tree

It was four o’clock on Sunday, 23 June 1839, the second year of Queen Victoria’s reign. Far away from England, on a hill in the shadow of Mount Lebanon, only the hum of cicadas stirred in the suffocating afternoon. The white stone walls and roofs of a house – as high and formidable as a small fortress – seemed to hover in the heat-distorted haze, above a handsome grove of olive trees. Round about there were other hills and ridges, crisscrossed with terraced fields, and gashes of that same chalky, porous stone. In the distance, bells pealed from the tower of a monastery; perhaps the only hint of what a European might recognize as kindred civilization. These hills were renowned as ancient cemeteries for the Greeks, Romans and Phoenicians, their warrens of tombs crammed with sarcophagi and hidden treasures invisible to the eye; superstition had allowed them to remain undisturbed for centuries.

Amid clouds of dust, half a dozen household servants scurried along the dirt path leading down to the village of Djoun, bringing with them a skittish collection of mares, donkeys and goats, the sturdiest saddled with hastily-packed bags and whatever furniture could be lashed into place, such things of value they hoped would compensate for unpaid wages. A boy clutched a red leather-bound book filled with strange divinatory symbols he did not understand.

In her bedroom with its stone-cut windows, the woman they called Syt Mylady was dead. Her open eyes stared straight ahead. A white turban was bound tightly around her skull-cropped grey hair. Incense smouldered in an earthenware saucer and candles had burnt to waxy stubs. She had died in the house which she had first glimpsed more than a quarter of a century earlier, not realizing then that it would become the one true object of her ambitions. How the light had glittered and danced about her then! Light, which she craved as a young woman, light that was exhilarating and alive under a cobalt-blue sky.

For the last seven years she had remained within her fortress walls, leaving her private quarters only to walk in her garden whenever it pleased her, at any hour of night or day. She would visit her mares, rest her hand on their warm flanks as they slept, or lie under her bitter orange trees, scrutinizing the constellations.

Now her body lay on coarse Barbary blankets, on a low-slung bed that was nothing but five planks nailed together, tilted slightly to incline her head. She was dressed in her customary night-dress – a chemise of cotton and silk, a white, quilted abaya and with a striped pale red and yellow keffiyeh tied under her chin, the way she had learned from the Bedouin. Her fingers still gripped a crooked staff with a naïve carving at the top shaped to resemble a ram’s head.

In death, her features – which were those of an old woman, for she died in her sixty-third year – seemed to soften. Her face was very pale and gaunt, making what some had affectionately called her famous Chatham nose look even more pronounced. This was the same unmistakable nose that had perched defiantly on the faces of four generations of Pitts before her, including not only two of England’s most outstanding and powerful Prime Ministers, father and son – both wartime leaders – but also ‘Diamond’ Pitt, her great-great-grandfather, curmudgeon of the first order and maker of the family fortune. It was his ability to thrive in an alien country, and by a combination of boldness and tenacity to rise from the rank of humble merchant, firstly, by founding a trading concern which grew formidable enough to rival even the East India Company, and later, to be Governor of Madras. She often used to say it was the blood of this Pitt that ‘flowed like lava’ through her veins.

Yet of all her relatives, aside from her mother, it was her grandfather, Pitt the Elder, she resembled most as she grew older. Indeed, by the age of fifty, she could have been his female incarnation: the same large, almond-shaped blue-grey eyes, with their direct, contemplative gaze; the refined oval face and high forehead.

These last few nights she had dreamed such living dreams. Herself, strong again, with all of her youth and boldness restored. Visions, half-dreams, half-memories from a time long distant, came to her. Footsteps echoed down familiar passageways, but this time she recognized them as the impatient, joyful steps of her younger self. Voices called to her, chided her in the old, loving ways. In sing-song French and Arabic: ‘ Ne verse pas des larmes, ma chère et belle marquise …’ and in English.

There she was again at Walmer, standing on the drawbridge in the sunlight near the shore, laughing after her straw hat as it blew away, her long dark chestnut hair like an aureole, and her blue dress billowing, a vision so unrestrained that the red-coated soldiers turned to stare. She had the ears and the heart of the Prime Minister. ‘Oh, Hester ,’ he would say, with the tender exasperation he reserved especially for her. Not the love between father and daughter, or brother and sister, but something possessive all the same. Their secret language when in company, much of it conveyed implicitly by the eyebrows and in sideways glances, gave no clue to the paroxysms of laughter they shared later in private. What could she not have achieved, had she set her mind to it? Before, when every expectation and anticipation she held of life had not been disappointed.

Читать дальше