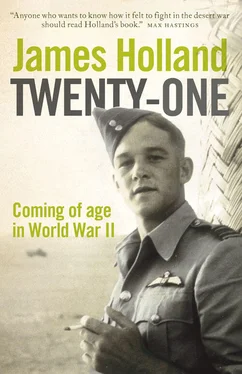

TWENTY-ONE

Coming of Age in the Second World War

James Holland

For Jimmy P

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Introduction

TWINS

Bill & George Byers

Tom & Dee Bowles

VILLAGE PEOPLE

Dr Chris Brown

Bill Laity

FRIENDSHIP

John Leaver & Fred Walsh

LOVE AND WAR

Warren ‘Bing’ Evans & Frances Wheeler

DERRING-DO

George Jellicoe

FIGHTER BOYS

Roland ‘Bee’ Beamont

Ken Adam

SPORTING BLOOD

Tom Finney

THE SHADOW WAR

Gianni Rossi

Lise Graf

BENEATH THE WAVES

Michael ‘Tubby’ Crawford

THE HEROIC ALLY

Wladek Rubnikowicz

BOY TO MAN

Hugh ‘Jimmy’ James

PARATROOPER

Heinz Puschmann

THE LAST BATTLE

Bill Pierce

Acknowledgements

Other Works

Copyright

About the Publisher

When Roland Beamont turned twenty-one, he was already a veteran of the Battle for France and the Battle of Britain, had shot down a dozen enemy aircraft, and won a Distinguished Flying Cross. A year later he was a squadron leader with over sixty pilots and groundcrew under his command; before he was twenty-four, he was in charge of an entire wing of three squadrons, operating a brand-new aircraft that he personally had played a significant role in developing.

Today in the western world none of us is forced to spend the best years of our life fighting and living through a global war. International terrorism may be a cause for worry, but it has directly touched few of our lives so far. For the generation who were born from the embers of the First World War, however, coming of age offered little cause for celebration. Youth was sapped as the young men – and women – were forced to grow old before their time. Mere boys found themselves facing life-threatening danger and the kind of responsibility few would be prepared to shoulder today.

These people were an extraordinary generation. The majority of those who fought were not professionals, but civilians who either volunteered or were conscripted as part of a conflict that touched the lives of every person in every country involved; ordinary, everyday people. One of the fascinations of the Second World War is wondering what we would have done were we in their shoes. Would we have willingly answered the call? Which of the services would we have joined? And would we have been able to control our fear and keep ourselves together amidst the chaos and carnage? Or would we have crumbled under the weight of terror and grief? ‘How did you deal with seeing friends killed in front of your eyes?’ is a question I have asked veterans over and over again. ‘You simply had to put it out of mind and keep going,’ is the usual reply. Would we have been able to do that in an age when we like to demonstrate mass expressions of grief and to turn to counselling as the panacea for any trauma? One veteran who had survived much of the war in North Africa and then the bloody slog up through Italy told me how when his house was recently broken into, someone offered him victim-support counselling. ‘I told her to bugger off,’ he said.

Nonetheless, most veterans believe we would behave exactly as they did. I would like to think so, but am not so sure. It was hard growing up in the 1920s and 30s. In Britain and the Commonwealth countries, communities had been devastated by the losses on the Western Front or at Gallipoli. In the United States, the Great Depression touched the entire nation; appalling poverty was rife. Healthcare was in its infancy and the standard of living – both in the USA and Europe – was way, way lower than it is now. Of the many I have interviewed, over fifty per cent had lost at least one parent by the time they were fifteen. Corporal punishment was a part of every child’s life. For the privileged, nannies and household staff ensured that parents often remained distant figures, while among the poor, a child might share a bed with his siblings and a bedroom with his mother and father. This is not to suggest that the twenty-one-year-olds of the war generation loved any less than we do today, or had fewer feelings; of course they did not. But perhaps their expectations were lower. Perhaps they were used to hardship in a way that is unfamiliar to us today. For those in Britain and her Dominions, the post-Great War generation also grew up during a time when wars and conflict were a part of British life. Even after the slaughter of the First World War, there were still plenty of Empire spats: in Ireland, Afghanistan, and along the North-West Frontier. Iraq. And while during the inter-war years, the United States largely stuck to her isolationist policy, life was every bit as hard in America, if not more so, than in Britain.

Perhaps we are too soft in this age of Health and Safety, when the threat of litigation means we are mollycoddled and protected more than ever before. Certainly we are less interesting. For all its horrors, no one can deny that the Second World War provided human drama on an enormous scale. The First World War, despite the terrifying ordeal of the trenches, did not touch as many lives as the war of 1939–45, where in Europe, certainly, the majority of civilians, as well as combatants, found themselves in the front line. Britain suffered considerable aerial bombardment, severe rationing, displacement of many thousands of men, women and children and dispatched its young men all around the globe to fight for a better world. By 1945, the United Kingdom had sent off so many men to war that there were almost no reserves of manpower left. Yet compared to Germany, Italy, Russia or Eastern Europe, Britain got off lightly. So, too, did the United States, but this is not to demean their huge losses. Of the front-line formations in northwest Europe and Italy, America suffered 120 per cent casualties between D-Day and VE Day. In the Pacific, the trauma for US troops was even worse, where they suffered unimaginable horror as they battered their way from one tiny dot in the ocean to another. The Battle for Okinawa, raging while in Europe the Allied armies were enjoying the fruits of victory, was one of the bloodiest, if not the bloodiest, battle of the entire war.

No one in their right mind would wish another world war, but no matter how terrible it may have been, many who lived through it will also admit that when facing death every day, they never felt more intensely alive. When one said goodbye to friends or family, one might well be doing so for the last time, so worrying over trivialities was pointless, and petty disagreements and squabbles were often cast aside. Carpe diem was not a catchphrase but a state of mind, and this meant that most people were far better at living back then than we are today. Communities were drawn together by the war. Britain as a whole was more united than it has been since; the same can be said of the United States. There was a collective understanding that the burden of war needed to be shared. This has long gone. As every year takes us further away from the war, so we become more selfish, more materialistic, more interested in the minutiae of life.

Читать дальше