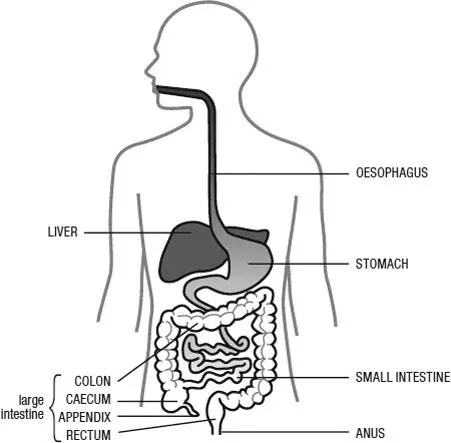

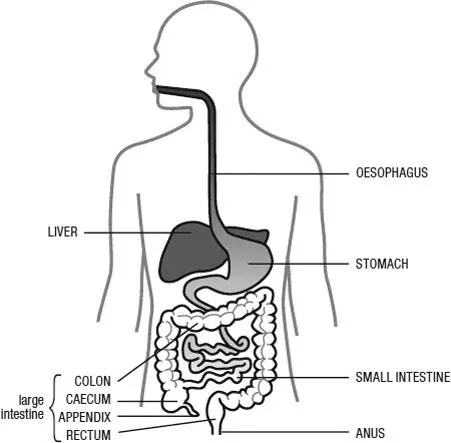

Just outside the safe-house created by the appendix is a teeming metropolis of microbes, in the heart of the microbial landscape of the human body – the tennis-ball-like caecum, to which the appendix is attached. This is the epicentre of microbial life, where trillions of individual microbes of at least 4,000 species make the most of the partially digested food that has passed through round one of the nutrient-extraction process in the small intestine. The tough bits – plant fibres – are left over for the microbes to tackle in round two.

The colon, which forms most of the length of the large intestine, running up the right-hand side of your torso, across your body under your rib cage, and back down the left-hand side, provides homes for microbes, numbering one trillion (1,000,000,000,000) individuals per millilitre by now, in the folds and pits of its walls. Here, they pick up the scraps of our food and convert them into energy, leaving their waste products to be absorbed into the cells of the colon’s walls. Without the gut’s microbes, these colonic cells would wither and die – whilst most of the body’s cells are fed by sugar transported in the blood, the colonic cells’ main energy source is the waste products of the microbiota. The colon’s moist, warm, swamp-like environment, in parts completely devoid of oxygen, provides not only a source of incoming food for its inhabitants, but a nutrient-rich mucus layer, which can sustain the microbes in times of famine.

Because HMP researchers would have to cut open their volunteers to sample the different habitats of the gut, a far more practical way of collecting information about the gut’s inhabitants was to sequence the DNA of microbes found in the stool. On its passage through the gut, the food we eat is mostly digested and absorbed, both by us and our microbes, leaving only a small amount to come out the other end. Stool, far from being the remains of our food, is mostly bacteria, some dead, some alive. Around 75 per cent of the wet weight of faeces is bacteria; plant fibre makes up about 17 per cent.

At any one time, your gut contains about 1.5 kg of bacteria – that’s about the same weight as the liver – and the lifespans of individuals are a matter of just days or weeks. The 4,000 species of bacteria found in the stool tell us more about the human body than all the other sites put together. These bacteria become a signature of our health and dietary status, not only as a species, but as a society, and personally. By far the most common group of bacteria in the stool are the Bacteroides , but because our gut bacteria eat what we eat, bacterial communities in the gut vary from person to person.

The gut microbes aren’t just scavengers, though, taking advantage of our leftovers. We have exploited them too, especially when it comes to outsourcing functions that would take us time to evolve for ourselves. After all, why bother having a gene for a protein that makes Vitamin B12, which is essential for our brain function, when Klebsiella will do it for you? And who needs genes to shape the intestine’s walls, when Bacteroides have them? It’s much cheaper and easier than evolving them afresh. But, as we will discover, the role of the microbes living in the gut goes far beyond synthesising a few vitamins.

The Human Microbiome Project began by looking only at the microbiotas of healthy people. With this benchmark set down, the HMP went on to ask how they differ in poor health, whether our modern illnesses could be a consequence of those differences, and if so, what was causing the damage? Could skin conditions like acne, psoriasis and dermatitis signal disruption to the skin’s normal balance of microbes? Might inflammatory bowel disease, cancers of the digestive tract and even obesity be due to shifts in the communities of microbes living in the gut? And, most extraordinarily, could conditions that were apparently far removed from microbial epicentres, such as allergies, autoimmune diseases and even mental health conditions, be brought on by a damaged microbiota?

Lee Rowen’s educated guess in the sweepstake at Cold Spring Harbor hinted at a much deeper discovery. We are not alone, and our microbial passengers have played a far greater role in our humanity than we ever expected. As Professor Jeffrey Gordon puts it:

This perception of the microbial side of ourselves is giving us a new view of our individuality. A new sense of our connection to the microbial world. A sense of the legacy of our personal interactions with our family and environment early in life. It’s causing us to pause and consider that there might be another dimension to our human evolution.

We have come to depend on our microbes, and without them, we would be a mere fraction of our true selves. So what does it mean to be just 10 per cent human?

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.