Some people took it even worse: in a letter to his friend Edvard Grieg, the Norwegian poet Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson wrote of Tristan and Isolde that it was ‘the most enormous depravity I have ever seen or heard, but in its own crazy way it is so overwhelming that one is deadened by it, as by a drug’. He found the plot to be immoral, he continued, ‘but even worse is this seasick music that destroys all sense of structure in its quest for tonal colour. In the end one just becomes a gob of slime on an ocean shore, something ejaculated by that masturbating pig in an opiate frenzy.’ When Wagner published the libretto of his gargantuan epic The Ring of the Nibelung , before he had written a note of the score, it provoked the pioneer psychiatrist Theodor Puschmann to publish a pamphlet called Richard Wagner: A Psychiatric Study , which roundly described its subject as a monomaniac and a psychopath. Nietzsche, too, after succumbing for a while to extreme Wagnolatry, turned violently away from him, proclaiming that Wagner was not a composer at all, comparing him unfavourably to Bizet. Recently, the British composer Thomas Adès described Wagner’s music as a fungus. ‘It’s a sort of unnatural growth. It’s parasitic in a sense – on its models, on its material. His material doesn’t grow symphonically – it doesn’t grow through a musical logic – it grows parasitically. It has a laboratory atmosphere.’ By contrast, Baudelaire said, after hearing the overture to Tannhäuser for the first time, that the music expressed ‘all that lies most deeply hidden in the heart of man’.

This was something quite new. Or maybe something very old. Something like Dionysiac possession, perhaps. From the beginning, Wagner got under people’s skin. He didn’t care whether his music gave formal satisfaction, or whether it struck people as being beautiful or exciting or dramatic. He was trying to bypass the audience’s analytical brain. His aim was the unconscious, the emotional underbelly, the murky depths of human experience. Feelings were what interested him, he said, not understanding. So it’s hardly surprising that Wagner’s music bothers people. It was meant to. It’s what he set out to do. He wanted to overwhelm his audiences – literally, to knock them off centre. He was a man without boundaries, and he wanted his audience’s boundaries to overflow too.

No wonder that the theatre was where he found himself. The theatre was, indeed, at his very core. He came from a theatrical background: his stepfather was an actor, as were several of his brothers and sisters. He wrote plays from an early age, he staged shows in his model theatre, he gave highly charged recitations. All his life, he acted, joyously giving himself over to amateur theatricals and giving electrifying performances of his own librettos. As with Charles Dickens, it was said of him by shrewd judges that had he chosen to make a living in the theatre, he would have been the greatest actor of his time. There are similarities between the two men. Like Wagner, Dickens created epics from his imagination by sheer willpower, epics teeming with archetypal figures; both men were given to great treks up mountains and down valleys; both of them had an uncanny relationship to animals. These parallels only go so far; the contrasts between them are sharp, but in their way, equally illuminating – Dickens with his essentially comic vision, Wagner with his tragic view of life; Dickens’s art at heart carnival, Wagner’s profoundly hieratic; Dickens deeply in touch with his inner child, Wagner directly connected to his inner infant.

The book I have tried to write aims to give a sense of what it was like to be near that demanding, tempestuous, haughty, playful, prodigiously productive figure, but also to place him in his world. Wagner belongs as much to the history of ideas and indeed to the history of the nineteenth century as he does to the history of music. I am not a musician, either as performer or as musicologist. I am a well-informed music lover, but it would be entirely inappropriate for me to attempt musical analysis. All I can write about is the effect of the music. I am slightly comforted by the fact that this is the only way Wagner ever wrote about music. You will search his copious writings in vain for an analysis of his highly idiosyncratic and complex compositional practice. This originality of procedure is a vital part of what makes him extraordinary, and I have noted the evolution of his musical means. But what has fascinated me above all has been how Wagner served his talent, his exceptional loyalty to it, however rackety a life he might have been leading, however much pressure there might have been to betray it, however hopeless his situation might have seemed. Wagner is in some senses an unlikely hero, but his custodianship of his gifts, despite the reverses of fortune and the vagaries of his temperament, counts as heroic and inspiring, while his personality in all its extremity belongs to one of the most fascinating of all the occupants of the human zoo.

***

Wagner has been written about at greater length than any other composer. Superb books, some short and some hernia-inducingly long, have covered him from every possible angle; primarily interested as I am in how he lived his life day-to-day, my main source has been his own words, in his copious published writings and especially, perhaps, in the letters, great tracts of which have been translated into English. Above all, I found that my most sustained sense of the man came from a book I had somewhat dreaded reading – his two-volume autobiography, My Life , published privately from 1870 to 1880. In the event, it turned out to be as vivacious and candid as the greatest artists’ autobiographies, every bit as compelling and stimulating as Benvenuto Cellini’s or Berlioz’s – and about as reliable. The circumstances of the book’s writing (dictated to his then mistress, Cosima von Bülow, at the behest of his besotted patron Ludwig II, edited and brought to press by an equally – at that stage – doting Nietzsche) mean that its truth is rarely pure and never simple, but it leaps off the page. At the very least, it tells us how he wanted to be seen by the world, which was by no means as a plaster saint. It is the work of a master dramatist, which is how he saw himself.

On 26 August 1876, as the last notes of the first performance of The Twilight of the Gods died away in the newly built Festspielhaus, in the tiny Bavarian town of Bayreuth, 2,000 people sat shaken, inspired, enchanted – or appalled. Among them were the musical aristocracy of Europe: Liszt, Saint-Saëns, Tchaikovsky, Anton Rubinstein, Grieg and Bruckner, along with a good sprinkling of the actual aristocracy of Europe, two emperors, three kings, a handful of princes, two grand dukes. All of them, or almost all of them, were swept along on a cataclysm of emotion to equal anything that happened on stage that evening.

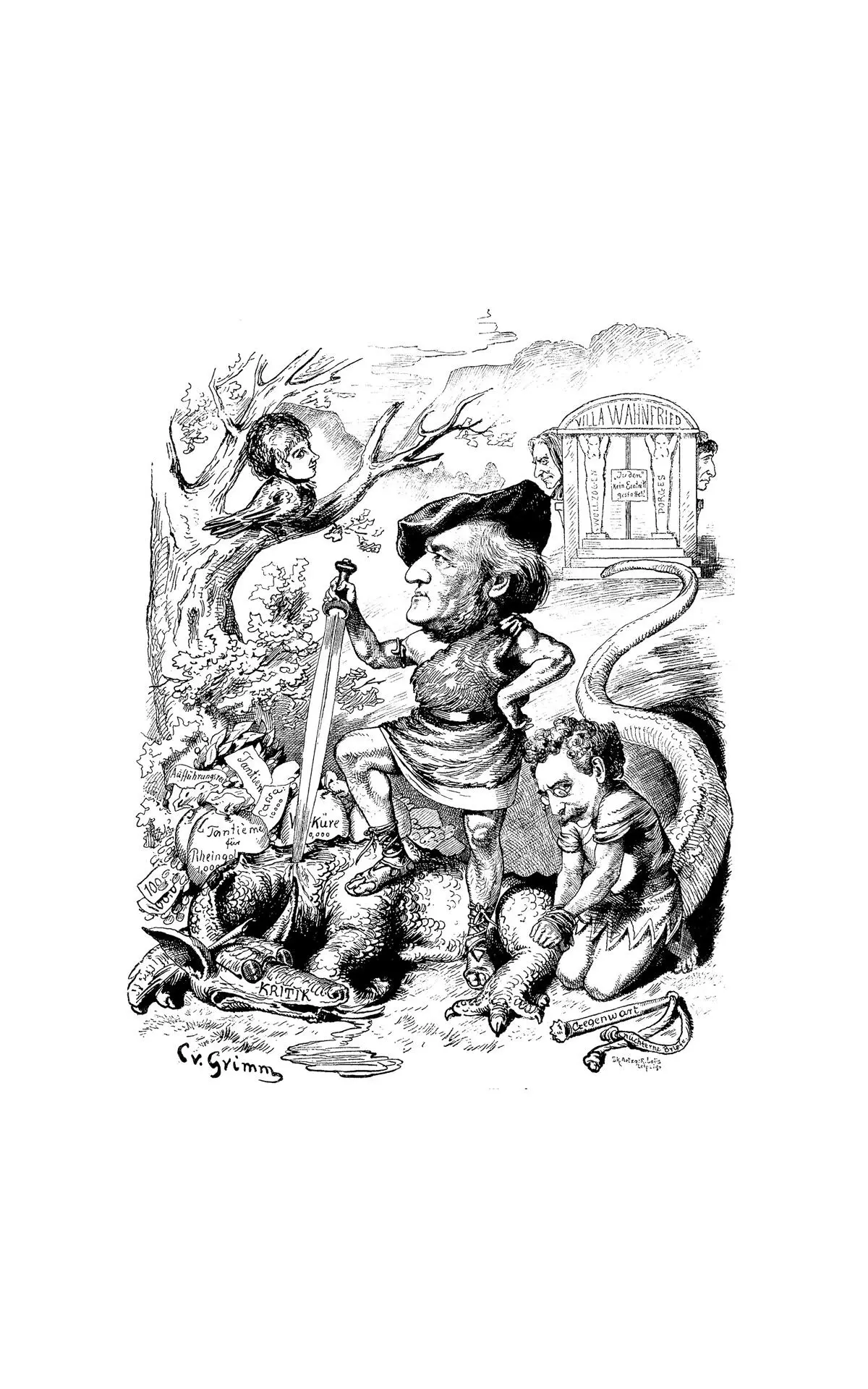

As the applause grew and grew, and before singers or conductor or designer or choreographer had appeared in front of the curtain to acknowledge it, a diminutive, stooping figure, familiar not just to the faithful but to the cultured world at large, the subject of a dozen photoshoots, two dozen portraits and a thousand cartoons, made his way somewhat lopsidedly to the front of the stage; his disproportionately huge head with its madly bulging eyes was topped by a floppy velvet cap set at a rakish angle. This man, this tiny man, sixty-three years old, but looking, Tchaikovsky thought, ancient and frail, was the hero of the hour, the sole architect of the vast four-day, fifteen-hour epic, every one of whose thousands and thousands of words and thousands and thousands of notes he had created, unleashing onto the vast stage gods and dwarves, dragons and songbirds, women warriors on horseback and maidens disporting themselves in the Rhine, digging deeply and unsettlingly into the subconscious, discharging in his audience emotions that were oceanic and engulfing – this man was the architect of all that; the architect, indeed, in all but name, of the very theatre in which the heaving, roaring audience sat. There he stood before them, the self-proclaimed Musician of the Future. He held a hand up, and in the ensuing silence, in the marked Saxon accent which he never made the slightest attempt to lose, he said: ‘Now you’ve seen what I want to achieve in Art. And you’ve seen what my artists, what we, can achieve. If you want the same thing, we shall have an Art.’

Читать дальше