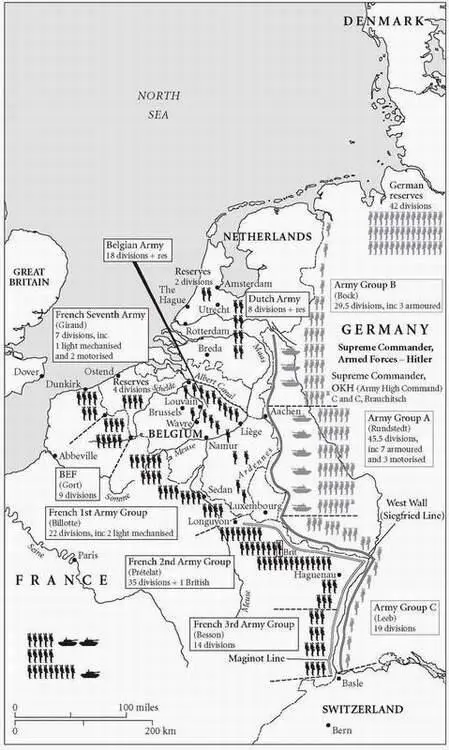

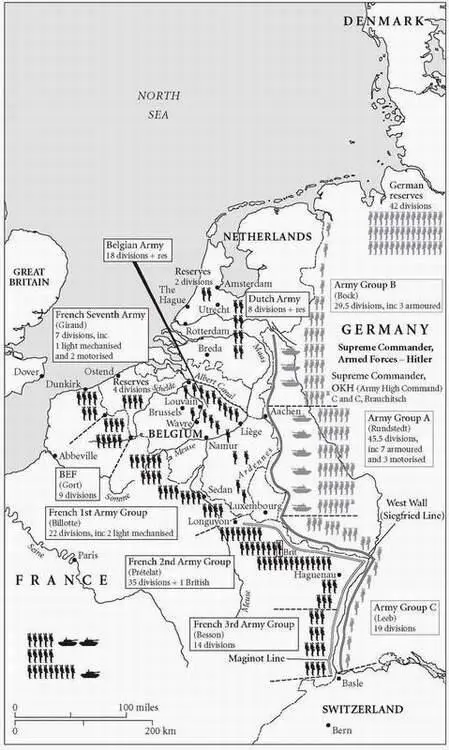

No more than his nation did the prime minister grasp the speed of approaching catastrophe. The Allied leaders supposed themselves at the beginning of a long campaign. The war was already eight months old, but thus far neither side had displayed impatience for a decisive confrontation. The German descent on Scandinavia was a sideshow. Hitler’s assault on France promised the French and British armies the opportunity, so they supposed, to confront his legions on level terms. The paper strengths of the two sides in the west were similar—about 140 divisions apiece, of which just nine were British. Allied commanders and governments believed that weeks, if not months, would elapse before the critical clash came. Churchill retired to bed on the night of 10 May knowing that the Allies’ strategic predicament was grave, but bursting with thoughts and plans, and believing that he had time to implement them.

Events which tower in the perception of posterity must at the time compete for attention with trifles. The BBC radio announcer who told the nation of the German invasion of Belgium and Holland followed this by reporting: ‘British troops have landed in Iceland,’ as if the second news item atoned for the first. The Times of 11 May 1940 reported the issue of an arrest warrant at Brighton bankruptcy court for a playwright named Walter Hackett, said to have fled to America. An army court martial was described, at which a colonel was charged with ‘undue familiarity’ with a sergeant in his searchlight unit. What would soldiers think, demanded the prosecutor, on hearing a commanding officer address a sergeant as ‘Eric’? Advertisements for Player’s cigarettes exhorted smokers: ‘When cheerfulness is in danger of disturbance, light a Player…with a few puffs put trouble in its proper place.’ The Irish Tourist Association promised: ‘Ireland will welcome you.’ On the front page, a blue Persian cat was offered for sale at £2.10 s : ‘house-trained: grandsire Ch. Laughton Laurel; age 7 weeks—Bachelor, Grove Place, Aldenham’. Among Business Offers, a ‘Gentleman with extensive experience wishes join established business, Town or Country, capital available.’ A golf report on the sports page was headed: ‘What the public want.’ There was a poem by Walter de la Mare: ‘O lovely England, whose ancient peace/War’s woful dangers strain and fret.’

The German blitzkrieg was reported under a double-column headline: ‘Hitler strikes at the Low Countries’. Commentaries variously asserted: ‘Belgians confident of victory; ten times as strong as in 1914’; ‘The side of Holland’s economic life of greatest interest to Hitler is doubtless her agricultural and allied activities’; ‘The Military Outlook: No Surprise This Time’. The Times ’s editorial column declared:‘It may be taken as certain that every detail has been prepared for an instant strategic reply…The Grand Alliance of our time for the destruction of the forces of treachery and oppression is being steadily marshalled.’

A single column at the right of the main news, on page six, proclaimed: ‘New prime minister. Mr Churchill accepts’. The news-paper’s correspondence was dominated by discussion of Parliament’s Norway debate three days earlier, which had precipitated the fall of Chamberlain. Mr Geoffrey Vickers urged that Lord Halifax was by far the best-qualified minister to lead a national government, assisted by a Labour leader of the Commons. Mr Quintin Hogg, Tory MP for Oxford, noted that many of those who had voted against the government were serving officers. Mr Henry Morris-Jones, Liberal MP for Denbigh, deplored the vote that had taken place, observing complacently that he himself had abstained. The news from France was mocked by a beautiful spring day, with bluebells and primroses everywhere in flower.

‘Chips’ Channon, millionaire Tory MP, diarist and consummate ass, wrote on 10 May: ‘Perhaps the darkest day in English history…We were all sad, angry and felt cheated and out-witted.’ His distress was inspired by the fall of Chamberlain, not the blitzkrieg in France. Churchill himself knew better than any man how grudgingly he had been offered the premiership, and how tenuous was his grasp on power. Much of the Conservative Party hated him, not least because he had twice in his life ‘ratted’—changed sides in the House of Commons. He was remembered as architect of the disastrous 1915 Gallipoli campaign, 1919 sponsor of war against the Bolsheviks in Russia, 1933-34 opponent of Indian self-government, 1936 supporter of King Edward VIII in the Abdication crisis, savage backbench critic of both Baldwin and Chamberlain, Tory prime ministers through his own ‘wilderness years’.

In May 1940, while few influential figures questioned Churchill’s brilliance or oratorical genius, they perceived his career as wreathed in misjudgements. Robert Rhodes-James subtitled his 1970 biography of Churchill before he ascended to the premiership A Study in Failure . As early as 1914, the historian A.G. Gardiner wrote an extraordinarily shrewd and admiring assessment of Churchill, which concluded equivocally: ‘ “Keep your eye on Churchill” should be the watchword of these days. Remember, he is a soldier first, last and always. He will write his name big on our future. Let us take care he does not write it in blood.’

Now, amidst the crisis precipitated by Hitler’s blitzkrieg, Churchill’s contemporaries could not forget that he had been wrong about much even in the recent past, and even in the military sphere in which he professed expertise. During the approach to war, he described the presence of aircraft over the battlefield as a mere ‘additional complication’. He claimed that modern anti-tank weapons neutered the powers of ‘the poor tank’, and that ‘the submarine will be mastered…There will be losses, but nothing to affect the scale of events.’ On Christmas Day 1939 he wrote to Sir Dudley Pound, the First Sea Lord: ‘I feel we may compare the position now very favourably with that of 1914.’ He had doubted that the Germans would invade Scandinavia. When they did so, Churchill told the Commons on 11 April: ‘In my view, which is shared by my skilled advisers, Herr Hitler has committed a grave strategic error in spreading the war so far to the north…We shall take all we want of this Norwegian coast now, with an enormous increase in the facility and the efficiency of our blockade.’ Even if some of Churchill’s false prophecies and mistaken expressions of confidence were unknown to the public, they were common currency among ministers and commanders.

His claim upon his country’s leadership rested not upon his contribution to the war since September 1939, which was equivocal, but upon his personal character and his record as a foe of appeasement. He was a warrior to the roots of his soul, who found his being upon battlefields. He was one of the few British prime ministers to have killed men with his own hand—at Omdurman in 1898. Now he wielded a sword symbolically, if no longer physically, amid a British body politic dominated by men of paper, creatures of committees and conference rooms. ‘It may well be,’ he enthused six years before the war, ‘that the most glorious chapters of our history have yet to be written. Indeed, the very problems and dangers that encompass us and our country ought to make English men and women of this generation glad to be here at such a time. We ought to rejoice at the responsibilities with which destiny has honoured us, and be proud that we are guardians of our country in an age when her life is at stake.’ Leo Amery had written in March 1940: ‘I am beginning to come round to the idea that Winston with all his failings is the one man with real war drive and love of battle.’ So he was, of course. But widespread fears persisted, that this erratic genius might lead Britain in a rush towards military disaster.

Читать дальше