No American or European expedition could compare in size to the flotillas launched by the Chinese emperor Yung-lo in the first half of the fifteenth century, some of which included 27,550 men and ventured as far as the east coast of Africa and perhaps beyond. When China chose to disband her fleets of discovery, Portugal became the world’s leader in exploration. Under the guidance of Prince Henry the Navigator, Portugal developed a new type of vessel called the caravel, specifically designed for exploration. Based on Egyptian and Greek designs and only seventy feet long, with shoal draft to keep from running aground on unknown coasts, the caravel enabled Portugal to become the first European country to round Africa’s Cape of Good Hope and, in 1498, reach the fabled shores of India. By that time, Spain had launched its own expeditions, placing its hopes in an Italian mariner named Christopher Columbus. Columbus insisted that the fastest way to the East was to sail west, and when he subsequently came upon the islands of the Bahamas and the Caribbean, he stubbornly insisted that they were what he had been looking for all along – the Spice Islands of the East Indies. Three hundred and forty-six years later, the history of exploration had come full circle as a nation from the New World Columbus refused to believe existed launched its own voyage of discovery.

With the U.S. Ex. Ex., America hoped to plant its flag in the world. Literally broadening the nation’s horizons, the Expedition’s ships would cover the Pacific Ocean from top to bottom and bring the United States international renown for its scientific endeavors as well as its bravado. European expeditions had served the cause of both science and empire, providing new lands with which to augment their countries’ already far-flung possessions around the world. The United States, on the other hand, had more than enough unexplored territory within its own borders. Commerce, not colonies, was what the U.S. was after. Besides establishing a stronger diplomatic presence throughout the Pacific, the Expedition sought to provide much-needed charts to American whalers, sealers, and China traders. Decades before America surveyed and mapped its own interior, this government-sponsored voyage of discovery would enable a young, determined nation to take its first tentative steps toward becoming an economic world power.

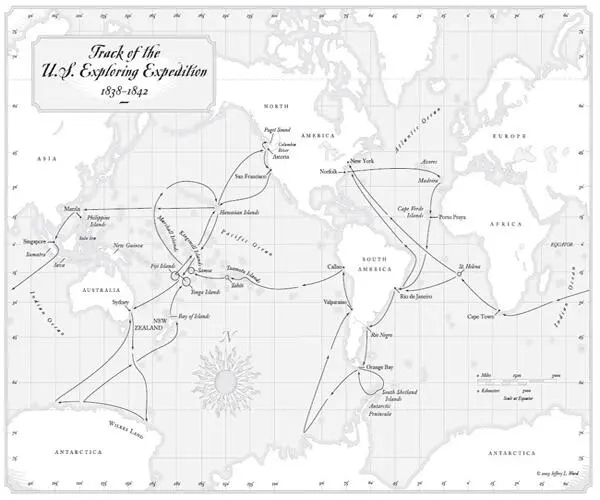

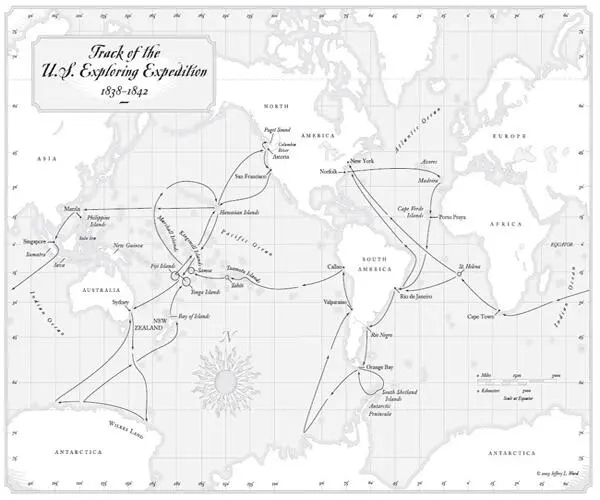

The Expedition was to attempt two forays south – one from Cape Horn, the other from Sydney, Australia, during the relatively warm months of January, February, and March. The time in between was to be spent surveying the islands of the South Pacific – particularly the little-known Fiji Group. The Expedition’s other priority was the Pacific Northwest. In the years since Lewis and Clark had ventured to the mouth of the Columbia River, the British and their Hudson’s Bay Company had come to dominate what was known as the Oregon territory. In hopes of laying the basis for the government’s future claim to the region, the Ex. Ex. was to complete the first American survey of the Columbia, and would continue down the coast to California’s San Francisco Bay, then still a part of Mexico. By the conclusion of the voyage-after stops at Manila, Singapore, and the Cape of Good Hope – the Expedition would become the last all-sail naval squadron to circumnavigate the world.

By any measure, the achievements of the Expedition would be extraordinary. After four years at sea, after losing two ships and twenty-eight officers and men, the Expedition logged 87,000 miles, surveyed 280 Pacific islands, and created 180 charts – some of which were still being used as late as World War II. The Expedition also mapped 800 miles of coastline in the Pacific Northwest and 1,500 miles of the icebound Antarctic coast. Just as important would be its contribution to the rise of science in America. The thousands of specimens and artifacts amassed by the Expedition’s scientists would become the foundation of the collections of the Smithsonian Institution. Indeed, without the Ex. Ex., there might never have been a national museum in Washington, D.C. The U.S. Botanic Garden, the U.S. Hydrographic Office, and the Naval Observatory all owe their existence, in varying degrees, to the Expedition.

Any one of these accomplishments would have been noteworthy. Taken together, they represent a national achievement on the order of the building of the Transcontinental Railroad and the Panama Canal. But if these wonders of technology and human resolve have become part of America’s legendary past, the U.S. Exploring Expedition has been largely forgotten. To understand why, we must look to the Expedition’s leader and the young officer who began the voyage as his commander’s biggest fan.

It had taken more than a decade to get the U.S. Ex. Ex. under way. By 1838, years of political infighting had severely damaged the Expedition’s credibility with the American people. But the turmoil made no difference to a twenty-two-year-old naval officer named William Reynolds. Reynolds was a passed midshipman – the pre-Annapolis equivalent of a Naval Academy graduate, who after several years of sea duty and study had passed a rigorous series of examinations. For Reynolds, the U.S. Ex. Ex. was the voyage of his young life, and on October 29, 1838-seventy-two days after the squadron’s departure – he poured out his enthusiasm into the pages of his journal. “And behold! Now a nation which a short time ago was a discovery itself … is taking its place among the enlightened of the world and endeavoring to contribute its mite in the cause of knowledge and research. For this seems the age in which all men’s minds are bent to learn all about the secrets of the world in which they inhabit.” Reynolds then turned his attention to the Expedition’s commander, Charles Wilkes, a controversial choice to lead such an ambitious undertaking. “Captain Wilkes is a man of great talent, perhaps genius,” Reynolds declared. After describing his leader’s extensive scientific and navigational background, he concluded, “In my humble opinion, Captain Wilkes is the most proper man who could have been found in the Navy to conduct this Expedition, and I have every confidence that he will accomplish all that is expected.”

Months later, after the Expedition had rounded Cape Horn, plunged south into the icy Drake Passage, and surveyed the island paradises of Polynesia, Reynolds would return to this passage in his journal. Over the reference to Wilkes he would scrawl, “great mistake, did not at this time know him.”

Reynolds would not be alone in changing his opinion of Charles Wilkes. By the end of the voyage, most of the Expedition’s officers had grown to despise their commander. The feelings were mutual. Wilkes would bring charges against several of his officers, who then countered with charges of their own, meaning that what might have been the triumphant return of the U.S. Ex. Ex. became clouded by a series of courts-martial.

According to common practice, all the Expedition’s officers had been required to keep journals that they were to surrender to their commander at the end of the voyage. Unbeknownst to Wilkes, Reynolds kept two journals: an official log and a secret, far more personal journal that would eventually expand to two volumes and almost 200,000 words. Today these big, twelve-by-twenty-inch unpublished journals reside in the archives of Franklin and Marshall College in Reynolds’s ancestral home of Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

Sensitive and well-read, Reynolds was a natural writer, and his journals contain some of the best descriptions of the sea to come from a nineteenth-century American’s pen. But the journals are much more than the chronicle of a four-year voyage. Along with the twenty – one letters he wrote to his family back home, the journals tell the story of one man’s coming of age amid the ice floes of the Antarctic, the coral reefs of the South Seas, and the giant pines of the Pacific Northwest.

Читать дальше