In other words, can you cough up a bit for the kids?

This was construed by the Queen as a piece of common insolence, as was made pretty evident by the tone in which she batted it back. Clearly she thought it iniquitous that she should be expected to shell out. Her Prime Minister, Viscount Lord Salisbury, was the recipient of the bleat. It was ‘most unjust’, wrote the Queen, ‘that she, in her old age, with endless expenses, should be asked to contribute’. Furthermore, she considered herself ‘very shamefully used in having no real assistance for the enormous expense of entertaining’ (at her own Golden Jubilee). Did not Salisbury realise what all this guzzling cost?

Next day she had another seethe at the ingratitude of the masses, via their Parliament. ‘The constant dread of the House of Commons is a bugbear. What ever is done you will not and cannot conciliate a certain set of fools and wicked people who will attack whatever is done.’13

These ‘fools and wicked people’ were actually the taxpayers, a large number of whom were living in abject poverty – which in Her Majesty’s view was about all the excuse they had for not understanding the price of Cristal champagne. Is this letter not as illuminating as it is astonishing? The richest woman on earth considered poor people who wouldn’t give her money ‘wicked’.

‘Oh, but she was a wrenching, grasping, clutching covetous old sinner, and closed as an oyster.’ I vandalise Dickens’s Christmas masterpiece, but his description of Ebenezer Scrooge is appropriate here. I think Dickens found his Miss Havisham in Queen Victoria – his creation a bitter old woman in white, and his muse this caustic old broken heart in endless black. Since the death of her husband Albert in 1861 she had lived in a perpetual funeral, grieving for her lost love and cut off from reality like Havisham in her rotting wedding gown.

The Victorians were subjects of this wretched widow, and in her presence kept a straight face. You had to polish your boots, assume a stiffened aspect, and pretend that everything in the world was serious. Fun was behind her back. In my view, Victoria’s permanent grief invented Victorian hypocrisy. You couldn’t get your hand up at an endless funeral, and had to pretend outrage if somebody else did. This ethic of counterfeit rectitude survives in not a few British newspapers to this very day.

But then, the name of the game is expediency: what do you want to make people think? Politics is reducible to that last defining question: who do you prefer, our liars or theirs?

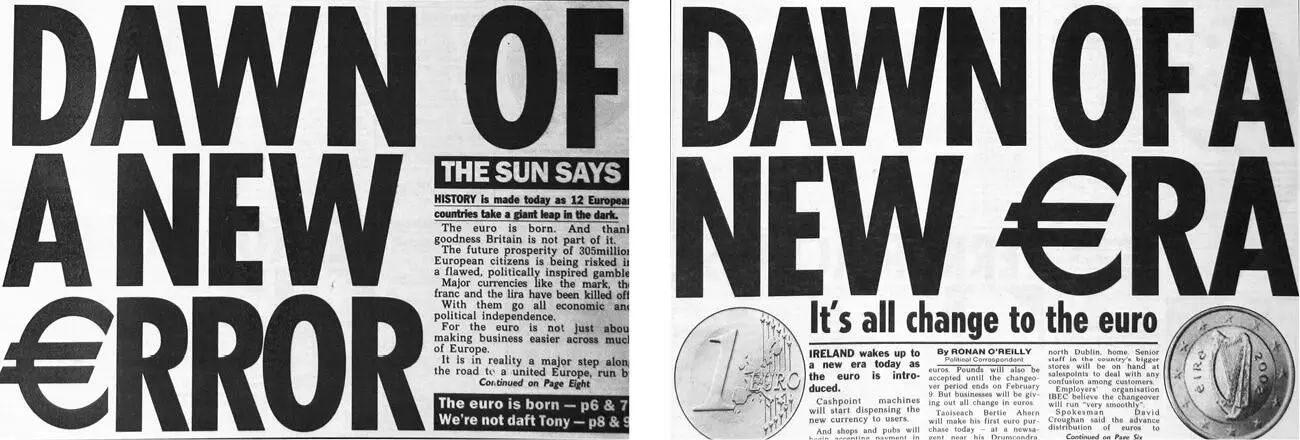

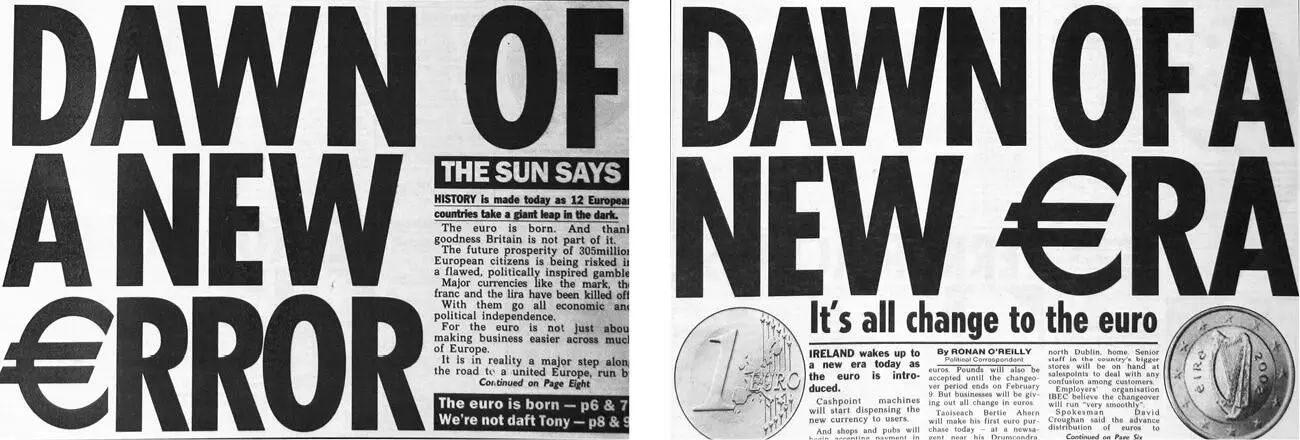

I reproduce the following because they save me writing a paragraph (and also because they serve as a vivid metaphor for the so-called official ‘Ripper Files’ of the Metropolitan Police). They come from the same newspaper, on the same day, but for a different audience. I always imagined a ‘balanced view’ at Mr Rupert Murdoch’s Sun meant a big pair of tits given equal prominence towards the camera. But this demonstrates that it too is capable of a little political sophistication. These two front pages concern the introduction of the euro. The one on the left is for the British reader, whose government is anti-European, and that on the right is for the Irish, whose government is pro.

The problem for the Victorians (and some of the wilder of the Ripperologists) was that they equated ‘evil’ with ‘insane’. In terms of nailing our Whitechapel monster, this is a mistake; but the Victorian public were conditioned to think in this direction by the police and by the newspapers.

Jack the Ripper was no more ‘insane’ than you or me. A psychopath, yes, but not insane. Was Satan insane? I don’t think so. For a while he was part of the in-crowd, a dazzling angel, Lucifer, the Bringer of Light. God didn’t kick him out of heaven because he was a nut, but simply because he was a nasty piece of work. During his reign, Henry VIII had 72,000 people put to death, and he also liked to cut ears and noses off. Was Henry insane? Probably not, just a Tudor despot who was intolerant of Catholics and others who didn’t subscribe to his theological diktat .14

Is Iago insane? Not noted for his difficulty with words, the greatest writer who ever lived gave this infinitely evil bastard but one line of explanation: ‘I hate the Moor.’ What if it’s as simple as that? With all reverence to Shakespeare, I will change one word: ‘I hate the Whore.’

Jack wasn’t the first, or the last, to make women a target of hate.

He went over there, ripped her clothes off, and took a knife and cut her from the vagina almost all the way up, just about to her breast and pulled the organs out, completely out of her cavity, and threw them out. Then he stooped and knelt over and commenced to peel every bit of skin off her body and left her there as a sign for something or other .

The italics aren’t mine, but Jane Caputi’s, whose book The Age of Sex Crime this comes from.

‘Left her there as a sign for something or other’.

As with much in Caputi’s book, her judgement here is precise. Although her description echoes aspects of the Ripper’s crime scenes, she’s actually writing about a squad of American soldiers who have just beaten and shot a Vietnamese woman to death. The perpetrator here is a representative of USAID. ‘Such crimes are indistinguishable from the crimes of Jack the Ripper,’ writes Caputi; ‘both are meant to signify the same thing – the utter vanquishment and annihilation of the enemy.’15

You don’t have to be ‘insane’ to cut people up, no matter how fiendishly you do it. You just have to hate enough. The Whitechapel Murderer was a beast who hated women (one young American woman in particular), but no way was he insane.

In 1889 an American lawyer wrote about the Ripper scandal in a Boston legal journal called the Green Bag . Considering his piece is contemporary, it is quite remarkable in its perceptions, and is not remotely taken in by the forest of nonsense being put out at the time. It’s far too long to reproduce in its entirety. This edited version therefore is mine, as are the emphases.

It is surprising that, in the present cases, there has been a failure to discover the perpetrator of the deeds; for they have not been ordinary murders. Not only are the details as revolting as any which the records of medical jurisprudence contain; they are also marked by certain characteristics which at first sight would seem to afford a particularly strong likelihood of the crimes being cleared up. The very number of the crimes, the almost exact repetition of the murderer’s procedure in each, the similarity of hour and circumstances, the elaborate mutilation of the bodies … these things might not unnaturally be expected to give some clue.16

My kind of lawyer. I couldn’t agree more, exploration of the words ‘marked by certain characteristics’ being the aspiration of this book.

Yet this abundance of circumstance gives none. So far from giving a clue, they would seem to conspire to baffle the police .

The writer goes on to dismiss the theory of a ‘homicidal maniac’ as an unreliable proposition:

It is the very atrocity of the Whitechapel murders that gave rise to the theory of their being the work of a madman. It is not a novel line of reasoning, this. Only let the deed be surpassingly barbarous, and the ordinary mind will at once leap to the conclusion that it was a maniac who wrought it. Now, the inference is quite fallacious. Some of the most barbarous murders on record have been perpetrated by admittedly sane men – men on whose perfect soundness of mind no doubt has ever been cast. The mutilation of the bodies of these wretched women in East London, taken by itself, is no indication whatever of insanity on the part of the perpetrator of the deeds. The craft and the cunning evinced in the murders seems little to consist with insanity. The rash and uncalculating act of the lunatic is not here. No doubt there are on record a few isolated cases of considerable caution being shown on the part of insane homicides; but we are not acquainted with any which approach to the present display of prudence and circumspection. The craftiness of these deeds is astounding; and the highest tribute to it is the fact that all attempts at detection have been made in vain hitherto. The actual execution of his foul deeds must have been swift and dexterous, and shows coolness of hand and steadiness of purpose. These things are all markedly in the direction of disproving insanity.17

Читать дальше