It felt like a return. She let the hot water batter her for at least ten minutes, opening her mouth to let it run in and out, then stepped from the tiny plastic tray into the hot cabin.

Esther put her hands on either side of the porthole and leant her forehead against the glass. The circular window looked out onto a serpentine collection of pipes, their paint peeling like a disease, and beyond them the port of Callao clanked and whined with industry.

So what if the ship was shitty, this was luck beyond her dreams. She knew it was irregular, probably illegal. Bulk carriers didn’t usually take paying passengers, only the bigger ships, the ones full of officers’ bored wives slowly drinking themselves to death on bleak industrial decks, armed with the civilized pretence that somehow every hour was cocktail hour. But if the drunken first officer and his malleable captain were happy to take her, she was ecstatic to accept. If it was against the law then, hell, it would be their heads on the block not hers.

And look what she got for free. The owner’s cabin, with shower. A seventies homage to Formica, flowered curtains and hairy carpet tiles, a cell of privacy that gave her a whole four days before they docked in Texas to make sense of the hundreds of pages of scribbles she’d made in her tattered red notebook, and more importantly, translate the pile of Dictaphone tapes. She grabbed a thin towel stamped with some other ship’s name, rubbed at her hair and sat down heavily on the foam sofa. This was going to get her a first. A big fat, fuck-off-I-told-you-I-could-do-it degree, the kind that only the lucky rich kids walked away with, regardless of what was between their ears. Right now she felt luckier than hell. She laid the excuse for a towel over her face and lay back with a smile.

Hold number three was still dripping from the high-pressure hoses that had bombarded its sides. Now it was ready to receive its cargo. The two massive iron doors were rolled back on rails to either side, and the water that dripped from the lip echoed as it fell thirty feet into the dark pit below.

Two Filipino ABSs leaning on the edge of the hold regarded the black-red interior impassively.

It was nothing more than an iron box, featureless except for a rusty spiral staircase winding its way up one wall, and scaling the other, a straight Australian ladder leading to the manhole that emerged on the deck. Soon both would be smothered under the hundreds of tonnes of loose trash that the crane was already spewing into holds one and two.

‘Fuck me, Efren. Where’d this shit come from?’

The smaller of the two sailors looked round lazily at the voice, with just enough animation in his body to avoid the accusation of insubordination. He grinned, and sniffed the air as if it was full of wind-blown blossom.

‘Come from Lima. Big pile. People live on it.’

Matthew Cotton felt like puking, helped of course by four double rum and Cokes, six shots of grappa and five beers; but mainly because the smell from the holds was so terrible.

‘Yeah? Well guess it ain’t a whole lot different to living in Queens.’

Though he hadn’t the remotest idea what his senior officer was referring to, Efren Ramos stood on one leg, smiled through gapped teeth and nodded. Matthew could have sworn they were going back to Port Arthur empty, but of course the suits at Sonstar would rather piss on their own grandmothers than have one of their ships burn fuel without earning cash. If they were struggling for a decent load of ore then he guessed the trash made sense.

Matthew didn’t give a shit. He was on his way back to his cabin to sleep this one off. Then he would get up in time for dinner and start work on a whole new stretch of drunkenness. That was what mattered. Keeping it topped up. Keeping it all nice and numb.

He turned with a flick of the hand that meant ‘carry on’ and walked unsteadily back to the accommodation block. The sun was getting low, but even so its heat was bothering him.

He wanted the shade of a cabin with the drapes pulled and the darkness of sleep, where for a few short hours nothing and nobody could reach him.

Darkness brought a sour breeze to the dock, and to the ship it brought a nightly invasion of mosquitoes that could not only locate every inch of exposed human skin, but even the fleshy parts of the countless rats that ran the length of their metal sea-going home.

Of course there were no rats on the Lysicrates . Every official form and inspection sheet signed and dated testified to that, claiming proudly that the ship was free from infestation. Indeed, that was what the circular metal plates ringing the top of the ropes were for, to stop the vermin boarding ship.

But there were rats. And on a ship this size, that meant there was plenty of room for them to carry on their daily, and right now, nightly, business.

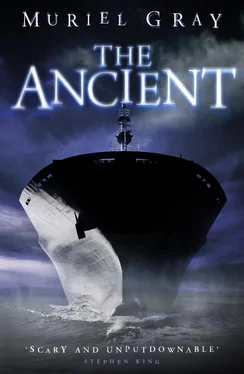

The MV Lysicrates was 280 metres long, weighed a dead tonnage of 158,537, had nine holds and a crew of twenty-eight, all Filipino except for two.

Even in this bleak industrial Peruvian port, the three other ships that lay alongside her were doing so with considerably more dignity, for the Lysicrates transmitted an air of decay that was hard to prove in detail, but impossible to ignore in essence.

It was the feeling that everything that was necessary to keeping her working had been done so only up to the legal limit and not an inch beyond.

The paint was peeling only in places that didn’t matter, the deck was not littered with hazardous material that constituted an offence, but neither was it particularly clean, and the hull was dulled with variegated horizontal stripes of algae that clearly were not planned to be dealt with as a priority.

Its depreciating appearance was not unusual in a working merchant fleet, particularly in this part of the world, but it was nevertheless an unsightly tub.

She had been lying in Callao for twelve days, which pleased the lower-ranking crew who had been taking the train daily to Lima, returning with a variety of cheap and unpleasant purchases they imagined might curry favour with loved ones back home.

But the turnaround time was unusual. The Lysicrates worked hard for her living. Of a fleet of ten ships, she was the eldest, and sailing as she was under a Monrovian flag of convenience, she was hardly the most prestigious. The dubious registration meant that the company could avoid practically every shipping regulation in the book, and by and large, it did. While she was still afloat, the ship’s task was to sail loaded, as often and as quickly as she could, so the fortnight’s holiday in port was not normally on the agenda. But no one was complaining. And no one seemed to mind that the captain had spent an unusual length of the time ashore. All anyone cared about was that the holds were filling up and it was time to go.

Just as Leonardo Becko, the cook, was putting the last touches to a dinner of steak and fries, the door of the last hold of the Lysicrates was rolling closed with a rumble.

That would mean it was only a matter of hours, and the crew were already milling around above and below deck, making the comfortable and familiar preparations to ensure the constant uncertainty of the sea would once more be under their control.

As they did so, the cargo in hold two shifted its bulk as the strip of daylight that moulded its rotting undulations narrowed steadily with the closing door, and the two massive metal plates met, enfolding it in darkness.

What air remained in the three to four foot gap between trash and steel seemed to sigh as the finality of the doors being secured subtly shifted the pressure. And then the broth of waste that was as solid as it was liquid was alone in the dark. Locked in. Silent. Content with its own decay.

Читать дальше