Roman legions landed in Britain in AD43 but do not appear to have bothered much about the small isolated communities in Cornwall, so Roman remains are sparse. After the departure of the Romans in AD410 the Anglo Saxons pushed the Celts into the Welsh mountains and to Cornwall. Many of those reaching Cornwall then crossed to their fellow Celts in France, but others remained, forming a community in Cornwall. The 5th and 6th centuries were remarkable for the number of Welsh, Irish and Breton Christian missionaries who came over to Cornwall, giving many unusual saints’ names to churches, towns and villages.

Cornwall had only been a part of Anglo Saxon England for just over 100 years when William the Conqueror landed at Pevensey Bay. By 1072 Cornwall was in Norman hands. The first towns in Cornwall began to spring up and other outward signs of Norman rule began to appear, notably Norman churches.

As with the rest of England, the structure of Cornish life was feudal and the landed gentry built substantial farmhouses. Growing prosperity and settled conditions, coupled with the religious fervour of the Cornish, resulted in a burst of church rebuilding. We owe many of the beautiful 15th century Cornish churches which remain today to this period. The Cornish gentry were wholeheartedly Royalist in the Civil War, and their men followed them into battle. In 1645, however, Cromwell’s well-trained forces moved westward and, when Pendennis Castle and St Michael’s Mount surrendered after long sieges, the Royalist cause in Cornwall was lost.

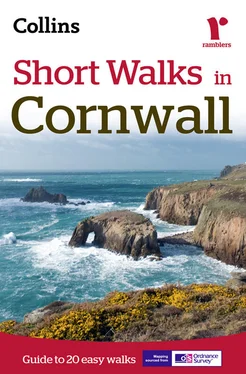

With King William III on the throne, Britain seemed to be set for quieter times. Cornwall had a flourishing fishing industry but from 1700 onwards it was mining that developed fastest. Shaft after shaft was sunk to extract ores, and, by the mid 18th century, Cornwall was the largest supplier of copper in the world. The copper boom lasted to about 1870. With new and cheaper sources being discovered abroad, the Cornish mines began to close. The dozens of derelict engine and boiler houses left behind are a familiar feature of the Cornish landscape today and they give an insight into the enormous scale of this industry in what are now relatively remote places. Several of the walks in this guide – St Agnes to Porthtowan, Cotehele and Calstock, Cape Cornwall and Levant, and Luxulyan – fall within areas designated under the Cornwall and West Devon Mining Landscape World Heritage Site.

Cornwall’s other traditional industry suffered a severe blow at about the same time as mining. The pilchard shoals, which provided a livelihood for so many fishing villages, disappeared from the coastal waters. There were still mackerel and other fish but there were no longer salted pilchards to send abroad in quantities. Cornish fishing has never fully recovered. In the latter half of the 19th century, the bleak outlook for Cornwall was transformed by the arrival of the railway. Fish, early vegetables and flowers were taken speedily to London and other centres. In the summer, Victorian holidaymakers began to discover the attractions of Cornwall’s magnificent coastline and laid the foundations of the present thriving tourist trade.

Walking tips & guidance

Safety

As with all other outdoor activities, walking is safe provided a few simple commonsense rules are followed:

• Make sure you are fit enough to complete the walk;

• Always try to let others know where you intend going, especially if you are walking alone;

• Be clothed adequately for the weather and always wear suitable footwear;

• Always allow plenty of time for the walk, especially if it is longer or harder than you have done before;

• Whatever the distance you plan to walk, always allow plenty of daylight hours unless you are absolutely certain of the route;

• If mist or bad weather come on unexpectedly, do not panic but instead try to remember the last certain feature which you have passed (road, farm, wood, etc.). Then work out your route from that point on the map but be sure of your route before continuing;

• Do not dislodge stones on the high edges: there may be climbers or other walkers on the lower crags and slopes;

• Unfortunately, accidents can happen even on the easiest of walks. If this should be the case and you need the help of others, make sure that the injured person is safe in a place where no further injury is likely to occur. For example, the injured person should not be left on a steep hillside or in danger from falling rocks. If you have a mobile phone and there is a signal, call for assistance. If, however, you are unable to contact help by mobile and you cannot leave anyone with the injured person, and even if they are conscious, try to leave a written note explaining their injuries and whatever you have done in the way of first aid treatment. Make sure you know exactly where you left them and then go to find assistance. Make your way to a telephone, dial 999 and ask for the police or mountain rescue. Unless the accident has happened within easy access of a road, it is the responsibility of the police to arrange evacuation. Always give accurate directions on how to find the casualty and, if possible, give an indication of the injuries involved;

• When walking in open country, learn to keep an eye on the immediate foreground while you admire the scenery or plan the route ahead. This may sound difficult but will enhance your walking experience;

• It’s best to walk at a steady pace, always on the flat of the feet as this is less tiring. Try not to walk directly up or downhill. A zigzag route is a more comfortable way of negotiating a slope. Running directly downhill is a major cause of erosion on popular hillsides;

• When walking along a country road, walk on the right, facing the traffic. The exception to this rule is, when approaching a blind bend, the walker should cross over to the left and so have a clear view and also be seen in both directions;

• Finally, always park your car where it will not cause inconvenience to other road users or prevent a farmer from gaining access to his fields. Take any valuables with you or lock them out of sight in the car.

Equipment, including clothing, footwear and rucksacks, is essentially a personal thing and depends on several factors, such as the type of activity planned, the time of year, and weather likely to be encountered.

All too often, a novice walker will spend money on a fashionable jacket but will skimp when it comes to buying footwear or a comfortable rucksack. Blistered and tired feet quickly remove all enjoyment from even the most exciting walk and a poorly balanced rucksack will soon feel as though you are carrying a ton of bricks. Well designed equipment is not only more comfortable but, being better made, it is longer lasting.

Clothing should be adequate for the day. In summer, remember to protect your head and neck, which are particularly vulnerable in a strong sun and use sun screen. Wear light woollen socks and lightweight boots or strong shoes. A spare pullover and waterproofs carried in the rucksack should, however, always be there in case you need them.

Winter wear is a much more serious affair. Remember that once the body starts to lose heat, it becomes much less efficient. Jeans are particularly unsuitable for winter wear and can sometimes even be downright dangerous.

Waterproof clothing is an area where it pays to buy the best you can afford. Make sure that the jacket is loose-fitting, windproof and has a generous hood. Waterproof overtrousers will not only offer complete protection in the rain but they are also windproof. Do not be misled by flimsy nylon ‘showerproof’ items. Remember, too, that garments made from rubberised or plastic material are heavy to carry and wear and they trap body condensation. Your rucksack should have wide, padded carrying straps for comfort.

Читать дальше