Cornwall is now classified as a county, but it was once a Celtic nation, like Brittany or Wales. This old Celtic Kingdom was where King Arthur and his knights were thought to have roamed, but history and legend have become so entwined that even historians cannot agree. What is certain is that Cornwall has been known for over a thousand years as a place of almost magical attraction.

Cornwall has retained a distinct cultural identity, a legacy from an historic isolation from the rest of the country. The county flag of St Piran, with its white cross on a black background, can be seen flying proudly in many places. The Cornish language was spoken until the 1700s and is still reflected in place names and surnames starting with Tre-, Polor Pen-, testifying to an ancient origin. Cornish is now a recognised minority language, which since the early 20th century has benefited from a conscious effort for revival.

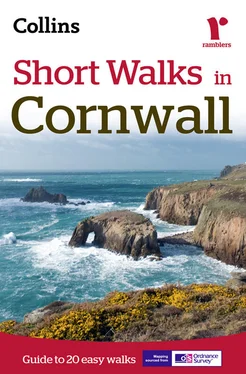

Parts of Cornwall are often windswept and treeless, presenting an image of a land of austere grandeur. The wildest place is Bodmin Moor, with its rocky summit tors and boulder-strewn flanks. Cattle, sheep and ponies graze the coarse grasses, bracken and heather. Brown Willy is the county’s highest point at 1377ft (420m). Along the coast of north Cornwall the sea has shaped dramatic coastal cliffs and steep-sided valleys. Here the land is gradually eroding under the relentless attack of the Atlantic Ocean. But despite this there are peaceful sheltered coves that are perfect for the holidaymaker, and the scenic beauty is without comparison. In contrast the southern coast provides gentler slopes, green fields and quiet bays of fine sand. The fishing villages are a photographer’s delight and everywhere the changeable maritime climate brings the clear light much loved by artists.

The dramatic and beautiful landscapes of Cornwall are largely a product of the geology beneath. The Lizard peninsula reveals the oldest rocks in the county, with a rare section of serpentine, formed deep in the Earth’s crust before being thrust up some 350 million years ago. However, as with the rest of the southwest peninsula, the greater part of the rock structure in Cornwall is of sedimentary origin, formed from beds of mudstone, sandstone and limestone laid down over 300 million years ago on the sea bed or on the beds of lakes. In some places river valleys cut deeply into these sedimentary rocks. In other places immense geological pressures have bent the strata into strange shapes, such as seen in the cliffs along the coast at Crackington Haven.

Rising out of this sedimentary plateau is the granite backbone of Cornwall. Granite is an igneous rock - one that has been thrust up in a molten state into the generally older sedimentary beds, cooling and hardening slowly, sometimes close to the surface. Forces such as the weather and sea have subsequently eroded it, leaving huge exposed bosses, or domes, of which Land’s End and Bodmin Moor are examples. The granite of Bodmin Moor was formed 287 million years ago and weathering along lines of weakness in the rock has created the distinctive ‘cheesewring’ formations often seen on the summits of tors such as Rough Tor. Neolithic Man also made his chamber tombs and entrance graves from the hard granite he found around him and this is one reason why there are more Neolithic remains in the Land’s End peninsula than in the whole of the rest of the south-west.

As well as creating the familiar bold and rugged scenery, the formation of granite rocks also made possible the Cornish mining industry. Cooling molten granite had the effect, through immense pressures and heat, of radically changing the sedimentary rock with which it came into contact, forming liquids and gases that eventually solidified as mineral ores. The coastal strip near Land’s End, as well as other areas such as St Agnes, are situated on these areas of contact - known as metamorphic aureoles - and this is where the ores of copper, tin and other metals such as silver and gold were found and exploited.

After the mining industry declined another Cornish industry developed that originated from the granite areas of the county. China clay, or kaolin was first discovered in Cornwall in 1746 and is still vitally important to the Cornish economy. Kaolin is granite that has decomposed over millions of years by the action of water originating deep in the earth’s crust. The clay is extracted from the quartz by powerful jets of water and the resultant fine-textured, pure white product is used for many purposes, from paper-making to face powder.

A diverse landscape produces a diverse flora and fauna, and the walks in this guide cover a range of habitats from the moorland of Bodmin and high exposed heath of Land’s End to the wooded valleys and warm sheltered coves of the south coast.

The cliff tops of Cornwall are carpeted in wild flowers. The colours range from pink thrift to the blue of spring squill and the yellow of golden samphire. Heather and gorse are plentiful. From the coast paths there are also some good vantage points to see birds and animals. Grey seals can sometimes be seen bobbing in the water or sunning themselves on the shore. The playful bottle-nosed dolphin and the common dolphin may be spotted from the cliff path, and you may even be lucky enough to glimpse a pilot whale. Bird life is particularly abundant all along the coast. On cliff faces you may see herring gulls, great black-backed and occasionally lesser black-backed gulls, fulmars, kittiwakes and jackdaws. On other shores you may find shag, cormorant, oyster catcher, rock pipit, pied wagtail and heron. The rare Cornish chough was absent for many years but a project is underway to promote the return of this emblematic bird to the county. Sightings of a wild chough should always be reported. Cornwall’s location on the south-west tip of Britain means that it also receives many migrant birds. The Island at St Ives, Land’s End and the Lizard are all particularly good for observing the arrival and departure of migrants, and Marazion Marsh near Penzance is an important migration stop, particularly for waterfowl and wading birds.

Inland, woodland walks such as Luxulyan will take you through oak, beech, sycamore and ash. Typical woodland flowers include bluebell and wood anemone, and there is a wide range of ferns, mosses, lichens and fungi.

In the warmer conditions after the Ice Age, all Cornwall except the highest ground became covered by forest. Mesolithic (Mid Stone Age) Man, who inhabited the land, was probably a nomadic hunter and fisherman. In about 3500BC Neolithic (New Stone Age) settlers arrived from the Atlantic seaboard of Europe. They used a variety of stone tools and weapons and founded settlements in forest clearings. Monuments of the Neolithic and Early Bronze Age people are the stone chamber tombs used for communal burials, known as quoits. Surmounted by huge stone slabs and covered originally by earthen mounds, there are a number to be found in Cornwall, including Lanyon Quoit seen on the Men-an-Tol walk. In about 2000BC the Beaker Folk arrived, bringing with them the knowledge of the working of metals. It was they who erected the imposing stone circles and standing stones all over Cornwall. Examples are the Merry Maidens and the Pipers.

The next migrants to reach southern Britain in about 700BC were the Iron Age Celts from northwest Europe. Organised in clans, they were constantly warring among themselves. Characteristic signs of this occupation are hill forts and cliff castles, several of which are passed on walks in this guide. They all feature a steep headland fortified by one or more ramparts, usually built across the narrowest part of the promontory, and The Rumps near Pentire is a good example.

Читать дальше