I kinda wonder if the music video is still relevant now as it was back inna day, when MTV ruled supremely. I ask Jonas if he still feels the same when he is making the videos today as he was back then.

‘I still enjoy making music videos but the problem I have is that everyone is worried about the content. There used to be a time when the videos were creative and free from all red tape, the brief was ‘just do something that we haven’t seen before, something that sticks out that people talk about’. And today the brief is that it’s gotta be ‘Iconic’. Making music videos has recently become a bit more like doing a commercial, but with an inexperienced client. The thing with advertising agencies is that they know what they are talking about. They know their audience. With the music world they are all smart-asses who all think they know what they’re talking about — but they really don’t. Out of that inexperience comes great creativity, that’s why I still love it!’

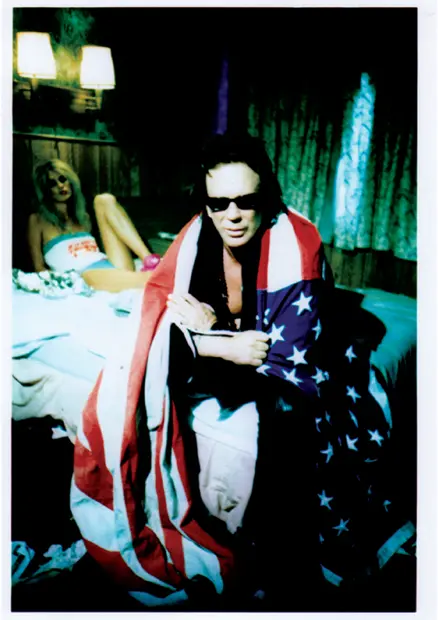

Back in 2002 when he made Spun, no one would even send Mickey Rourke a script, let alone cast him in a movie; he was seen as box-office poison by the fools who run the show, but Jonas ignored all this bullshit and cast him as ‘The Cook’ — one of Mickey’s finest roles to date. I give him total respect for that action alone. Jonas has recently completed shooting a $25m horror film, Horsemen, and continues to create amazing music videos and commercials around the world.

So I may be a bit biased (as I used to be an art director, hence the ADZ in my name) but advertising has had a massive influence on street culture and vice versa. In terms of audio/visual culture, adverts are not only massively influenced by street shit (usually they are always playing catch-up to what is really happening on the street), they also, once in a while, influence it. Okay, so right now the advertising industry is in a bit of a strange place as the Internet came along and changed everything. The web is a showcase of original ideas, created by everyone and anyone — it totally changed the way ad agencies worked, who were no longer an exclusive source of creative genius anymore.

Back inna day a full-scale ad campaign to launch a new product consisted of a couple of press ads, some outdoor and — the king of ads — a TV spot or two. Now all that has changed but some of advertising’s most respected players — and my personal heroes (Tony Kaye, Oliviero Toscaniro) — have made their names in advertising before moving on to bigger and better things. Take for instance the legendary Dunlop-Tested For The Unexpected TV ad from 1993, an advert that totally changed the face of how TV ads were made and watched. The most amazing visuals (an S&M mask-clad man, a grand piano on wheels driving across a bridge, black ball bearings), cut to a Velvet Underground song, it blew the genre apart. It showed that elements of street culture (the ad was drenched in pure street style and attitude) could be harnessed and used in the mainstream media without having to use the obvious images of things like break dancing youths. This ad was light years ahead of the game, and in turn influenced music videos, film which in turn had a direct influence on street culture.

‘The Dunlop TV ad was an incident where the stars all came together at the same point. I was working with a creative team from an ad agency Tom Carty and Walter Campbell — and they trusted me completely. I’d just come off making a terrible British Airways commercial which really went completely wrong, so I said to them, and their client — “If you want me to do this for you then you have to back off and let me do my thing otherwise I won’t be able to give you what you really want.” And they all did. Originally that script was “Open on a big frying pan with a car driving round the frying pan and it’s got these tyres.” That was what their idea was. And we completely changed it and got something out on TV that if it ran next week, it would be as radical as it was then.’

Tony Kaye

Advertising has now become an integral part of the street culture, as a lot of the new campaigns are what’s called ‘guerrilla’ — stuff that actually happens in the street, events that people can interact with and not merely watch. Advertising has become harder and harder to spot within the urban environment. Brands are hosting events, exhibitions, star-maker competitions, websites, publishing magazines, all of which appear to be non-branded, but are actually just vehicles for an energy drink, sneakers, or a pair of jeans, often using imagery, techniques and other ideas lifted directly from the sub-culture of the street. Sony executed a campaign where they used street artists in Berlin to advertise their PSP, much to the scorn of the Berlin public who worked out what was going on (they were being sold to by a huge corporation) immediately as the ‘street art’ went up. It didn’t matter how good the street art was, it was dismissed as it was just advertising.

But that said, advertising is part of the day-to-day whether we like it or not. There are direct lines of influence between street culture and advertising, but more recently it has been a one-way street with street culture (including its online presence) being absorbed, regurgitated and then spat out as advertising. This will change as society is always hungry for the ‘new’ and in the not-too-distant future it will be the turn of advertising to carry this torch.

www.alifenyc.com

The purest attitude and motives go into the creation of their constantly amazing clothing range and other amazing products and projects. Alife is the strongest brand that’s come out of the New York bombing movement. Alife started out as a creative space on Orchard Street in the Lower East Side. They chose this spot as 1) it was affordable and 2) it was an area that people from all the other boroughs of Manhattan would not be opposed to coming to. Coming out of bombing you have to think about this shit! I sat down with Rob Cristofaro the founder of Alife.

‘I used to write graffiti and I decided to start this new thing — workshop, retail space — I guess it was a store but never had any experience doing any of that shit. Me and a few other dudes were like “we’re gonna start something” as there wasn’t anything going on. We started the plans in 1998 and by ‘99 we found the space and opened up shop in the Lower East Side, Orchard Street, which was basically at the time affordable rent as nobody was really down there. We didn’t know what the hell we were doing and were just like “fuck it, let’s just try this new jump-off and see where it goes.“’

Once they opened the space, Alife became their new tag and their mission was to get the name out there in any way possible: stickers, T-shirts, magazines, the same shit as usual; self-promotion is all bombing really, with no budget. They don’t pay for advertising and everything is hand done, independent street promotion. That’s not to say that if they had a big budget to go do some serious marketing, they would be going large on billboards, as I’m sure they’d still retain that no-budget attitude.

‘That’s the graffiti way — it’s like, “king, shit, fuck everybody else; fuck all crews, we’re by ourselves, no respect for really anybody else out here,” and that’s our shit: We’re gonna king New York. Alife was based on the street and before we opened our space we put the word out to the graffiti community — who were the only people we were in touch with — that we were opening a platform, a workshop, a creative space, and we wanted them to be involved. We had a meeting before we opened the store with 50-60 people. These were all the creative people before the shit became what it is. This was people like Espo, Reese, Kaws, the people that were graffiti writers but ready to take it to the next level and at the time there was no other venue for it.’

Читать дальше