‘Focus on the front row of the dress circle. That way you’ll lift your head up, and the audience will see your eyes and the whole of your face. And smile, girls. Smile.’

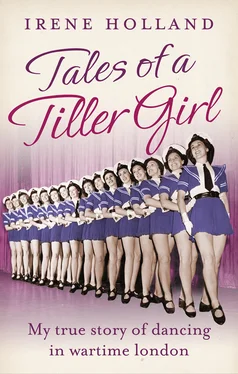

As I danced across that stage I made sure that I had the biggest, broadest smile on my face. But the strange thing was, it wasn’t forced or fake. I was genuinely happy, as I suddenly realised in that moment that my dream really had come true. Here I was, nearly ten years later, dancing like one of those fairies I’d seen in the pantomime at the Clapham Grand. Not only that, it was on the stage of the biggest theatre in the West End. Performing in front of that huge crowd gave me such a thrill.

‘If only Mum were here to see me,’ I thought to myself.

But there was no time to be sad, and soon I was curtseying to the King and Queen and basking in the audience’s applause. Everyone was on a high and even strict Miss Toni seemed pleased with our performance.

‘That was a job well done, everyone,’ she said, although her face still didn’t crack a smile.

I was still buzzing afterwards, and I didn’t want to take off my fairy costume and get changed back into my ordinary clothes, as that would mean it was all over. As I got ready to go home I watched the rest of my classmates being greeted in the dressing-room by their proud parents, who had all come to watch the show.

‘Oh, Daphne darling, you were absolutely wonderful,’ said her mother, handing her a red rose and a huge box of chocolates.

Others were being lavished with hugs and kisses and praise for their performance. I knew there was no one in the audience who was there for me, but I hadn’t expected there to be. As I squeezed my way out and headed to the Tube I refused to feel sorry for myself or let it get to me.

As part of your training at Italia Conti you were also sent off to appear in other productions during the school holidays. In the early Forties there were little variety theatres in every town and suburb, so there were endless opportunities to perform in summer seasons and pantomimes. I did a short tour with the Sadler’s Wells Opera in which I played a gingerbread child in Hansel and Gretel , and I appeared in a variety show in Brighton. There were no such things as chaperones in those days. We just got on a train on our own and got on with it. A lot of the time we had to find our own places to stay.

When I was thirteen we were sent to work at a pantomime at the Theatre Royal in King’s Lynn. Normally you wrote to the theatre where you were performing and they organised your digs, but our train was late into Norwich and by the time we got there that evening to speak to the stage manager it was all closed up.

‘What are we going to do?’ said my friend Ruth, who had been sent to perform in the show with me.

‘Don’t worry,’ I told her. ‘We’ll just find somewhere ourselves.’

So we ended up walking up and down the streets, knocking on doors to see if we could find a bed for the night. But nobody had any room for the two of us, and as it got later and later we were getting more and more desperate. Then we knocked on the door of a terraced house and an old man opened it.

‘We’re dancers working at the local theatre and we’re looking for somewhere to stay,’ I told him. ‘Do you think you might be so kind as to put us up for the night?’

‘Well, I’m sure I could sort summink out for a couple of lovely young ’uns like you,’ he said in his broad Norfolk accent.

He seemed like a nice, kindly man so we followed him into the house and he showed us his bedroom.

‘You ladies can ’ave this room and I’ll have forty winks downstairs,’ he said, giving us a toothless grin.

Ruth and I looked at each other in horror. The place was absolutely filthy and everything was covered in a sheet of dust. His bedroom had a strange musty smell and the sheets looked like they hadn’t been boiled up in the copper for years.

‘What shall we do?’ whispered Ruth when he went back downstairs. ‘This place is revolting.’

‘Beggars can’t be choosers,’ I said. ‘It’s getting late, and I don’t fancy wandering up and down for hours in the dark.’

Even though his house was filthy he seemed like a nice old fellow, and he was letting us stay for free. But neither Ruth nor I got much sleep that night. We both slept fully dressed on top of the bedclothes and we even left our coats on. Bed bugs were very common in those days and I spent most of the night scratching. Neither of us could wait to leave in the morning.

‘I feel so grubby,’ said Ruth. ‘Before we go to the theatre shall we go to the baths?’

Most towns and cities in the Forties had what were known as public baths. Sometimes our lodgings didn’t have much hot water to go round or even a proper bath, so they were a godsend when we were working away from home doing a show.

When we walked in there was a woman sitting at a little kiosk.

‘Ninepence for a first-class ticket or sixpence for second,’ she told us.

The only difference was that with the first-class ones you got two towels and a scoop of bath salts, and with the second-class ones you only got one towel.

‘Second will be fine,’ I said.

It was expensive enough for us as it was.

She handed us both a meagre piece of soap that had been cut from a big block. Soap was rationed during the war and you couldn’t get any nice, sweet-smelling ones, just this rock-hard green stuff that didn’t lather up no matter how hard you scrubbed. Shampoo wasn’t available either, so you had to use the same soap if you wanted to give your hair a wash, but I’d stopped doing that after I’d discovered how badly it stung my eyes.

‘I can’t wait to feel clean again,’ said Ruth as we went upstairs and sat on the second-class bench until the numbers on our tickets were called.

‘I know what you mean,’ I replied. ‘I still feel all itchy and I’m sure I heard rats scurrying around last night.’

I didn’t mind waiting in the public baths as it was all steamy and warm in there, and you could hear the sound of people singing echoing around the tiled walls. Finally it was our turn and an attendant showed me to my cubicle. It had a stone floor and a huge iron roll-top bath with copper taps but no plug in it.

‘Give me a shout when you’ve finished, love, and I’ll empty out the water for you,’ the attendant told me.

I suppose it was like that to stop anyone from running endless baths. It felt wonderful sinking into the piping hot water after spending the night in that filthy bed. After I’d got out I washed my clothes and underwear in the bathwater, and then got changed into some clean things. Whenever I went to the public baths I would always bring my dirty washing with me.

‘Thank you,’ I said to the attendant.

She went in and opened the tap to let the water out. It was also her job to collect any leftover pieces of soap. These would be melted down and made into a new block, although the thought of that always made me cringe a bit.

‘Ahh, that’s better,’ sighed Ruth. ‘I feel clean again.’

‘Now we’d better go and report in with the theatre,’ I said.

The stage manager was very apologetic about the mix-up with our lodgings.

‘Don’t worry,’ he said. ‘We’ve got you somewhere to stay. You won’t have to go wandering the streets again tonight.’

After morning rehearsals were over we went to get some lunch at the local British Restaurant. These were communal kitchens set up in towns and cities during the war to feed people who’d been bombed out of their houses or had run out of ration coupons, or just people like us who needed a cheap feed. For ninepence you could get a basic meal, such as a bowl of soup or a steaming plate of stew. Afterwards we traipsed round to our new digs, which was a big Victorian terrace house.

Читать дальше