For my lovely mum Kitty, who inspired me to achieve my dream.

And to my children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren, in the hope that you all find your passion in life, as I have in dancing.

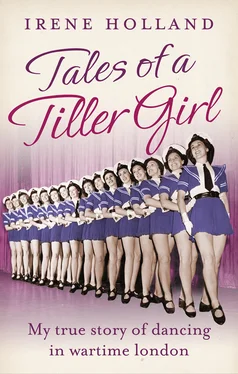

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

1. On Our Own

2. Bows and Bombs

3. Painful Goodbyes

4. Fairyland

5. Ballet in the Blitz

6. Treading the Boards

7. Briefly a Bluebell

8. Trying Out

9. Bright Lights

10. Sisterhood

11. Dancing with the Stars

12. Disaster Strikes

13. Making Mum Proud

14. War Wounds

15. Horror and High Tea

16. Man Trouble

17. The Final Curtain

18. New Beginnings

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Picture Section

Exclusive sample chapters

Moving Memoirs eNewsletter

Write for Us

Copyright

About the Publisher

The little girl walked down the hospital ward tightly clutching her mother’s hand. Nurses bustled up and down in their starched white uniforms and capes, and the smell of carbolic soap was overpowering. Finally they got to a bed at the end, which had the curtains drawn around it for privacy.

‘Come here, dear,’ said one of the nurses, lifting up the girl and sitting her on the bed so that she had a better view of the man lying in it.

He looked very thin and frail, and he had a nasty, hacking cough. Her mother passed the man a handkerchief, and as he patted his mouth the girl noticed bright red spots of blood splattered all over the white material.

Although just two years old, the child knew instinctively that it was serious. Maybe it was her mother’s tears that gave it away or the pale, gaunt face of the man lying in the bed. Every breath he took was so laboured and shallow and seemed to require so much effort that it almost sounded like his last.

‘Poor Daddy,’ she sighed.

You see, that little girl was me, and that was my first, last and only memory of my father, Edwin Bott.

I was born in 1930 in a nursing home on the edge of Wandsworth Common in south-west London. My brother, Raymond, was eleven years older than me and, like a lot of children, I think I was what you’d call a bit of a mistake! I was from a very musical background – my father was a cellist and my mother, Kitty, was a professional violinist. They had met in the orchestra pit while they were playing music for the silent films when Mum was seventeen and my dad was seven years older. When they first got married they lived in Oxford, and that’s where my brother was born, but then they moved up to London to play in the theatre orchestras. My father also used to play in a quartet on banana boats that would take passengers to Rio de Janeiro and bring bananas back. He would be away for weeks at a time, and the bananas he was given by the crew would be completely rotten by the time he got back home to London.

My name was Irene but everyone called me Rene. I was named after my father’s half-sister Rene Gibbons. She was a Goldwyn Girl, part of a glamorous company of female dancers employed by the famous Hollywood producer Samuel Goldwyn in the Twenties and Thirties to perform in his films and musicals. Many female stars got their big break in his troupes, including Lucille Ball and Betty Grable. Although I’d never met her, I’d seen from a photograph she once sent us that Rene was an incredibly beautiful woman. She looked like something from a Pre-Raphaelite painting, with her long auburn hair and huge green eyes. Unfortunately she and Mum never got along, I suspect probably due to a little bit of jealousy on my mother’s part, although she never really told me why.

‘I wanted to call you Violet,’ Mum used to say to me as I was growing up. ‘But your sneaky father went off to the town hall one day and registered your birth without me knowing.

‘When he came back and I saw the name Irene on your birth certificate there were a few fireworks, let me tell you.’

I could well imagine. My mother was only tiny but she had a sparky temper, that was for sure.

Sadly I was too young to remember Dad, apart from that one time when I had visited him in hospital. I was only two when he died of tuberculosis at the age of thirty-three. He had terrible asthma, so I think it affected him very quickly. It must have been horrible for my mother and Raymond to see him in so much pain as his lungs disintegrated and he constantly coughed up blood. There was no cure in those days and it was highly infectious. My brother and I were tested for it, but thankfully we were clear.

We’d always been comfortably off, but after my father died we were left destitute. My brother had to leave his private boarding school and it was a real struggle. Mum had a small amount from her widow’s pension so she decided to buy a 1920s house in London. But we were there less than a year as she couldn’t keep up with the mortgage payments. Eventually the house was repossessed and she lost her deposit. There were no Social Services then, and my mother couldn’t work because she had me and she’d lost all her income from Dad.

‘We’re going to have to move in with your grandmother and grandfather,’ she told me.

I was three by then and this is where most of my memories start. Her parents, Henry and Kate Livermore, lived in a large, three-storey Victorian terrace in Battersea, south-west London. We called them Gaga and Papa because my brother couldn’t say their names properly when he was little and those nicknames just stuck.

The house seemed huge to me as Raymond and I tore around it. There was a big sitting-room at the front with settees and an open fire and all this lovely antique furniture. A passageway led to a tiny scullery with a big copper pot with a fire underneath where you would boil your washing and a really tired-looking porcelain sink. There were no hot-water taps in those days, of course. Then there was a dining-room with a big range cooker that had a coal fire underneath a couple of hot plates and took hours to heat up. On the second floor there was another living-room, two bedrooms and a bathroom, and on the very top floor was a tiny, dusty attic room.

‘This is where we’ll live, children,’ Mum told me as we climbed up the steep staircase to the attic.

‘Where’s all the furniture, Mummy?’ I asked.

It was very dark and shivery cold, and there was hardly anything in it. But there was a double bed for Mum and me to share, a camp bed for Raymond and a little larder where we could keep our food.

There was only one very dim electric light up there, and one night while we were sitting there it went out. I screamed, as I was so afraid of the dark.

‘I’ll go and find out what’s happened,’ said Mum.

She went downstairs to have a look while I sat there, completely petrified. A few minutes later she came storming up the stairs holding a candle. I could tell by the look on her face that she was fuming.

‘I don’t believe it,’ she said. ‘They’ve cut us off.’

Mum hadn’t been able to afford to pay her share of money for the meter that week, so my grandparents had cut off the electricity supply to the attic. From then on, even though the lights were blazing downstairs, we had to make do with a single candle. Mum was absolutely furious.

I was too young to really understand at the time, but now looking back, no wonder. How awful to do that to their own widowed daughter at a time when she so needed their help and support. I was old enough to know it wasn’t nice, though.

Читать дальше