1 ...6 7 8 10 11 12 ...21 At this point Hess began picking out the politicians he wished to take into custody, taking them from their seats and ushering them from the hall to be sent away under armed guard to the home of a Nazi sympathiser, where they were to be held overnight.

In 1923, however, the thirty-four-year-old Adolf Hitler was still a novice at the taking and holding of power, and he quickly lost control of the situation. Within the Bürgerbräukeller a wave of patriotic anthem-singing, Nazi saluting and volatile speeches on everything from the incompetence of the Social Democrats to the evils of Communism took the initiative away from Hitler, and he failed to consolidate his position by sending his men to take over the key buildings and services of the city. By the following morning Hitler’s Putsch lay in disarray, and it was at the Bürgerbräukeller that the Times correspondent in Munich found him still: ‘a little man … unshaven with disorderly hair, and so hoarse that he could hardly speak’. 16

During the course of the night, Hitler’s failure to consolidate his position had been surpassed in naïveté by Göring, who, after eliciting promises from the captured Ministers (as officers and gentlemen) that they would not act against the Putsch , released all his leading prisoners. However, much to Göring’s surprised consternation, and Hitler’s absolute fury, they discovered that as soon as the politicians had been released, they promptly summoned the army to aid them in putting down the attempted coup. The final act of this fiasco was a gun-battle in central Munich that would soon enter Nazi folklore: fourteen Nazis died, Goring was wounded, and Hitler dislocated his shoulder when he tripped over and someone fell on top of him.

In the hours following the shoot-out, Hitler’s sense of self-preservation led him to find sanctuary with Karl and Martha Haushofer in their flat on Kolbergerstrasse, where he hid out for some hours. During this time Hitler and Karl Haushofer undoubtedly discussed what had occurred, what had gone wrong, and what would now ensue, for by 1923 Karl Haushofer had become important to both Hess and Hitler – the sage old expert on politics, nationalism and German ethnicity regularly gave the two up-and-coming politicians private lectures and political tutoring.

One of the significant facts about the 1923 Munich Putsch is that it marked a watershed in the Hess-Hitler relationship. Hess would come to prominence as the loyal Nazi who followed his Führer to Landsberg prison, near Munich, for a year of confinement after the failed Putsch , *during which time he acted as Hitler’s secretary whilst he wrote his vitriolic book on political ideology, Mein Kampf.

While they were incarcerated at Landsberg, Hitler and Hess were extensively tutored by Professor Karl Haushofer. Indeed, many of Haushofer’s geopolitical theories on Lebensraum , German ethnicity and nationhood, became adopted as Hitlerisms in Mein Kampf. In effect, Hitler was quite literally a captive audience to Hess and his political guru Karl Haushofer, receiving tutorials on the European balance of power, the distribution of peoples, ethnicity, colonies and nationalism.

Hess’s importance to Hitler at this time should not be underestimated. Their long conversations were not between Führer and obedient disciple, but rather between two close friends and political colleagues, and set the tone for Hitler’s future reliance on his loyal friend. In private they were not ‘Mein Führer’ and ‘Hess’, but ‘Wolf’ (Hitler) and ‘Rudi’ (Hess); often seated with them in their enforced seclusion – a tight-knit political commune in a sea of criminality – was Karl Haushofer.

At the end of the Second World War Haushofer would resolutely deny that he had made any contributions to Mein Kampf. However, during the 1930s he was not nearly so reticent. Deep within the microfilmed records of America’s National Archive in Washington DC are numerous Haushofer letters from the 1920s and thirties, in which the extent to which his theories influenced Mein Kampf is not concealed. Indeed, even in 1939, between a letter to the head of the Volksdeutsche Mitelstelle (German Racial Assistance Office), or VOMI, and a report on the exploitable resources of Poland, reposes a nine-point statement by Haushofer enumerating his credentials and his importance to the Volksbund für das Deutschtum im Ausland (the Committee for Germanism Abroad), known as the VDA, and listing amongst the accomplishments he was proud of his contributions to Hitler’s thinking, which appeared in Mein Kampf. 17

Rudolf Hess’s input into Mein Kampf was not insubstantial either. During Professor Haushofer’s interrogation by American Intelligence in 1945, he was asked: ‘Isn’t it true that Hess collaborated with Hitler in writing Mein Kampf ?’ The by now very elderly Haushofer replied unhesitatingly: ‘As far as I know Hess actually dictated many chapters in that book.’ 18

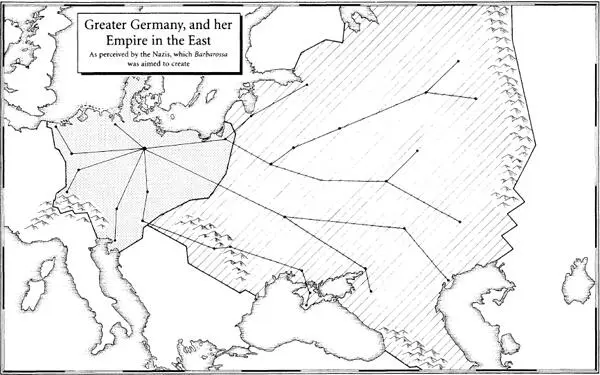

Hess was very much Professor Haushofer’s protégé, and as such had a keen understanding of the theories behind Lebensraum , the distribution of ethnic Germanic peoples across central Europe, and how this ethnicity could be mobilised in the future to create a Greater Germany and Reich.

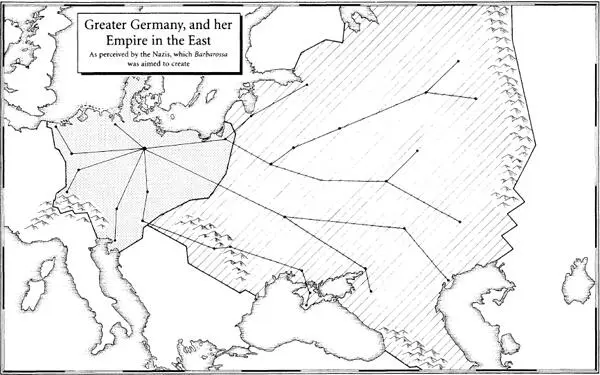

Haushofer’s original position had been that Germany’s living space should stretch from the Baltic to the Pacific. Hitler, however, was more circumspect, and advanced the view that if Germany were to conquer the east, it should initially aim to occupy only western Russia, using the Ural Mountains as a natural buffer between the Reich and Asia. This territory, Hitler proposed, would take Germany a century to exploit. In the summer of 1941, while Germany’s armies rolled ever eastward enjoying early successes under Operation Barbarossa, a relaxed Hitler became extraordinarily open about his aims in the east, and over dinner one evening confided to his guests:

We’ll take the southern part of the Ukraine, especially the Crimea, and make it into a German colony … [Russia] will be a source of raw materials for us, and a market for our products, but we shall take care not to industrialise it …

If I offer [people] land in Russia, a river of human beings will rush there headlong … In twenty years’ time, European emigration will no longer be directed towards America, but eastward.

Finally, he added whimsically:

The beauties of the Crimea, which we shall make accessible by means of autobahns – for us Germans, that will be our Riviera … [for] we can reach the Crimea by road. Along that road lies Kiev! And Croatia, too, a tourists’ paradise for us … What progress in the direction of the New Europe. Just as the autobahn has caused the inner frontiers of Germany to disappear, so it will abolish the frontiers of the countries of Europe. 19

This is a revealing insight into the world Hitler was attempting to create, a Reich that had been designed for him by Karl Haushofer.

The impression has always been given that the Second World War was Hitler’s attempt at total European and then world domination, but this is not necessarily completely accurate. The above statement, allied to Map 2, is a much closer approximation of what Hitler’s war objectives really were.

The Nazis’ rise to power took ten years of hard political struggle, during which the party grew into a membership that numbered well over a million souls disaffected with the Weimar Republic. From a handful of members of parliament, by 1933 the Nazis held the balance of power with over 70 per cent of the vote. Many of Hitler and Hess’s aspirations for the party had been accomplished, and their theories, as laid down in Mein Kampf , were about to be applied to the German nation. In the Germany of the 1930s, the majority accepted the concept of authoritarianism, of a ruling party which promised to take your children and turn out model citizens who would in turn have safe, if controlled, existences, free from the horrors of economic decline and the threat of the Communism. Through all this, at Adolf Hitler’s right hand stood Deputy-Führer Rudolf Hess, the upstanding, well-spoken, educated family man, who yearly took part in competition flying, and had no stigma of seediness – unlike other leading Nazis such as the drunkard Dr Robert Ley, or the appallingly anti-Semitic Julius Streicher.

Читать дальше