Deliciae, like iucundus (‘pleasant’), was part of the vocabulary Catullus used to communicate his poetic taste. These words prove difficult to translate in English, but for me deliciae in Poem 2 has become ‘apple of my girl’s eye’, since I venture also to suggest that the last three lines of Poem 2, which many commentators view as a distinct fragment, belong with his sparrow lines. Just as the little bird provides relief, Catullus imagines that Atalanta, the indomitable huntress of Greek myth, finds relief when a suitor beats her in a foot race – after she slows to pick up some golden apples – and wins her hand.

The nature of Poem 68 in the collection is problematic. Catullus addresses the first part of it to a certain Manlius, probably the young nobleman Manlius Torquatus, for whom he also wrote the wedding hymn at Poem 61 (other hymns may be found at Poem 34 and Poem 62: they have a marked formality). The second part is addressed to an Allius. The poem probably started life as separate poems. In this edition, I have demarcated the two main parts with a line break.

Like Lowell seeking the approval of Frost, Catullus spent time offering his work to fellow poets to edit, and digesting theirs in turn. He belonged not so much to a fixed coterie as to a loose set of like-minded individuals who enjoyed a shared language and poetic heritage. They knew that when Catullus asked for ‘salt’, he was seeking more than a condiment: he wanted wit and urbanity. It would be a pity to lose the word in a translation of his work.

In Poem 95, Catullus celebrates the publication of his friend and fellow poet Gaius Helvius Cinna’s work Zmyrna , which described an act of incest between a princess and her father. Catullus compares it favourably with some Annals by a certain Volusius, which in Poem 36 he describes with more colour as cacata carta (‘shit-smeared sheets’). There is a corruption in the text, but it seems likely that Volusius is described as coming from Hatria, near Padua, and producing ‘five hundred thousand’ verses in one year. Such productivity was reason enough for Catullus to despise him. Catullus, Cinna, Calvus, whom together Cicero would describe as poetae novi, ‘new poets’, were united in their preference for brevity and concision over verbosity.

This was a stylistic feature that Lowell, too, was taught to savour. The manuscript he carried to Robert Frost as a young man, he once recalled, was heavy with words. 6He had written, in barely legible pencil, an epic on the First Crusade in blank verse. Taking hold of it, Frost began to read as far as his eyes and patience allowed. ‘It goes on rather a bit, doesn’t it?’ Frost said, and retrieved from elsewhere in the room a copy of Keats’ Hyperion , which he read aloud, as Catullus did his own poetry, and circulated also in written form. 7Lowell would learn to refine his art, and to great effect.

Catullus received a similar education at the hands of the god Apollo – through the Greek poetry of Callimachus, one of the finest writers from the great Library of Alexandria. In the third century BC, Callimachus wrote of how the god instructed him to fatten animals for sacrifice, but keep his poetry slender, inventive, recherché, ‘even if you drive a narrower path’. 8In ‘The Road Not Taken’, Robert Frost proudly took the road ‘less traveled by’. Catullus worked in accordance with these precepts, and translated several of Callimachus’ poems from Greek into Latin. Catullus’ Poem 66, written from the viewpoint of a lock of hair that belonged to Queen Berenice II, wife of Ptolemy III Euergetes of third-century BC Alexandria, was a close translation of a Greek poem by Callimachus.

Poem 64, though Catullus’ longest surviving poem at over four hundred lines, adheres to Callimachus’ advice for reducing an otherwise long tale to a tight and erudite poem. It overflows with subtle allusions to the work of earlier poets, including Apollonius of Rhodes, author of the Argonautica, and Ennius, author of a Latin Medea. At the beginning of Poem 64 Catullus describes the flight of the Argo , which he viewed as the first ship ever to have sailed. It is so novel that he can refer to it only as a ‘flying chariot’. As often, the oars on which it sails are ‘palms of the hand’; these are delights which must be preserved in English.

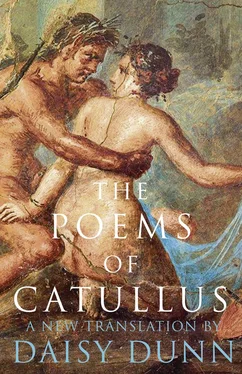

I came to translate Catullus’ poems in the process of writing Catullus’ Bedspread, a book about the poet’s life and work in which I explore the ‘flying chariot’ and characters of Poem 64. I challenged myself to keep as true to the Latin as I could – a difficult task since Latin is a far more economical language than English – while retaining the life and tone of the original verse. At times this called for interpolation: Catullus addressed several poems to ‘Mentula’ (‘Cock’), a none-too-flattering nom de plume for Caesar’s subordinate in the Gallic War, Mamurra. In Poem 7, where he speaks to Lesbia of the number of kisses he desires of her, Catullus uses the word basiationes. The standard Latin for kisses was oscula, but Catullus appears to have favoured basia because the word’s origins were probably Celtic. His native Verona was part of Gaul for as long as he lived. I have tried to convey the equivalent by using French, gros bisous, for basiationes , which gives the size of these great kisses, almost diminutives in reverse. 9

I felt that the bones of some of Catullus’ more striking constructions deserved airing in order that the spirit of the Latin can live on in the English. His poems occasionally read strangely in Latin. In Poem 22, for example, Catullus repeatedly refers to ‘the same man’, ‘that same man’, ‘the same fellow’, which some scholars have sought to explain as a hint that the poem’s subject, Suffenus, was in fact synonymous with Varus, the poem’s addressee. 10

Catullus used a variety of poetic metres. Poem 64 was written in hexameters, the metre of epic, which gave it more weight than many of his other poems, such as the elegiacs, which make up the last fifty poems in the book as it is arranged. Poem 63, in which Catullus describes a man named Attis castrating himself in honour of an ancient Eastern goddess (he refers to him from that point on as a ‘she’), was the first Latin poem to be written in galliambics, a feisty metre chosen to reflect the strangeness of the foreign rites: the goddess’ eunuch priests were known as galli.

I have not sought to recreate the Latin metres Catullus used. I wanted the freedom to render his words as I saw fit, and reflect on the difficulties of seeking an English equivalent for the sound of Latin verse. An elegiac couplet in English will not sound like a Latin elegiac couplet when read aloud. Robert Frost discovered the difficulty of replicating Latin metres when he decided to write his poem ‘For Once, Then, Something’, in hendecasyllables – one of Catullus’ favourite Latin metres – formed of eleven-syllable lines. ‘Everybody just thinks it’s my kind of blank verse,’ Frost said, at once delighted and vexed that his poem, ‘calculated to tease the metrists’, had succeeded in blinding his critics. 11

Gestures may still be made to reflect the sound of Catullus’ Latin, whilst making it appeal to the modern eye and ear. In the love poems, the languor of the Gallic tongue may still be heard. Catullus’ early Latin readers, though far more familiar with mythology and Greek literature than we are today, might still have had use of a commentary to read Poem 64. Attempts to reflect the sound of Catullus’ Latin have led me to shape stanzas out of the continuous text and shorten the line length in the earlier part of this poem, where the rhythm and sound of the ship, the Argo , moving through the water resounds clearly. It is hoped that this will aid with the reading of this richly complex poem. 12

Читать дальше