Our private thoughts were interrupted by a wild banging on the door and muffled shouting. Reluctantly, I eased up the lever and opened the door an inch.

‘Fuck’s sake! Lemme in. Lemme in!’ A helmeted shadow was trying to rip open the door. I held on grimly, not wishing to expose us any more to the outside world.

‘Sorry mate. No room in here … try the one next door …’ I barked through the gap. The shadow swore savagely and disappeared into the night. I slammed the door shut just as another shell screamed in, shattering the night.

‘Oi! You! Get the fucking periscope up!’ It was the corporal, up front somewhere. What was he on about now? Deathly silence. Nothing happened.

‘You in the commander’s seat! Get the periscope up and let’s get a fix on those flashes … work out where the bastards are firing at us from …’ Has be gone mad?

The unfortunate Dawson, who clearly had never been in an APC in his life, frantically started to tug at the various levers and knobs around him. He had no idea what he was supposed to be doing. I’d have been just as clueless. Another shell screamed in.

‘Fuck’s sake, fuck’s sake … get out, get fucking out!’ The corporal had finally lost his rag. A scuffle broke out up front as the shell exploded. In the darkness all you could hear above the high-pitched ringing in your ears were thuds, grunts and the occasional blow as Dawson and the corporal struggled with each other. Somebody whimpered, the APC rocked softly on its suspension, a few more grunts and blows and the unfortunate Marine was ejected from his seat.

Settled in the seat the corporal expertly flipped up the periscope and glued his forehead to the eyepiece. ‘Compass … somebody gimme a compass!’ he yelled without removing his eyes from the optic. His voice rose a note, ‘Shit! ’nother two flashes on the horizon … two rounds incoming!!’

I stared down at the luminous second hand of my watch … five seconds … it swept past ten seconds. Someone started to whimper, another’s breathing rose in volume, great gasping pants … thirteen seconds … my watch started to tremble. I was mesmerised by it … fourteen … fifteen – the air was ripped; two double concussions which rolled into each other. A collective sigh of relief swept through the APC.

‘Where’s that fucking compass?’ The corporal was at it again. Either he was barking mad or had simply been born without fear. He was still determined to get a fix on the guns. I dug out a Silva compass from my smock pocket and passed it up the APC.

‘Time of flight’s about fifteen seconds,’ I shouted up at him.

‘Good. Fifteen seconds, yeah?’ He seemed pleased. What difference did it make? Flashes, bearings, time of flight? The facts couldn’t be altered. We were stuck in this APC. Shells were landing somewhere to our front. A direct hit would destroy the vehicle. A very near miss would destroy it as well, and, with it, us. But I had a sneaking admiration for that unknown corporal. He was one of Kipling’s men, keeping his head and his cool while all around him were losing theirs. At least he was doing something , keeping his mind busy, warding off the intrusion of fear and panic – pure professionalism. I felt useless, unable to contribute in any way, jammed as I was in the rear and prey to my fears and imagination.

What were we doing sitting in an aluminium bucket between the building and the incoming rounds? Surely we’d be safer in the lee of the building, behind it? Another dreadful thought came to mind: the CVR(T) series of vehicles, of which this Spartan was one, were the last of the British Army’s combat vehicles which still ran on petrol. All the others – tanks, armoured infantry fighting vehicles, lorries, Land Rover and plant – ran on diesel. We were sitting on top of hundreds of litres of petrol ‘protected’ only by an aluminium skin. We’d sought refuge inside a petrol bomb. My mind imagined a near miss – red hot steel fragments slicing through aluminium, piercing the fuel tank, which we were sitting on, and wooooossssh .. . frying tonight! Fuck this! This was not the place to take cover.

‘Hey! Why don’t we just drive out of here, round the back of the building where it’s safer?’ I shouted at the corporal and anyone else who might care to listen.

‘No driver in the front,’ he shouted back, seemingly unconcerned. I don’t suppose the fuel thing had occurred to him.

‘We had this for four hours this afternoon … just sat here, froze and waited … shit myself,’ mumbled the staff sergeant opposite and then he added savagely, ‘I’ve fucking had enough of this shite!’

‘Another flash!’ screamed the corporal. Bugger him! Why did he have to be so efficient? I didn’t want to know that another shell was arcing towards us. This is the one that’s going to fry us!… three seconds … the panting started … five seconds … where were Corporal Fox and Brigadier Cumming? Where had they taken cover? … seven seconds . .. How had we got ourselves into this? How eager and consumed with childish enthusiasm we’d been, desperate not to miss out! How we’d raced down to TSG – and for what? … nine seconds. .. . Idiots! The lot of us.

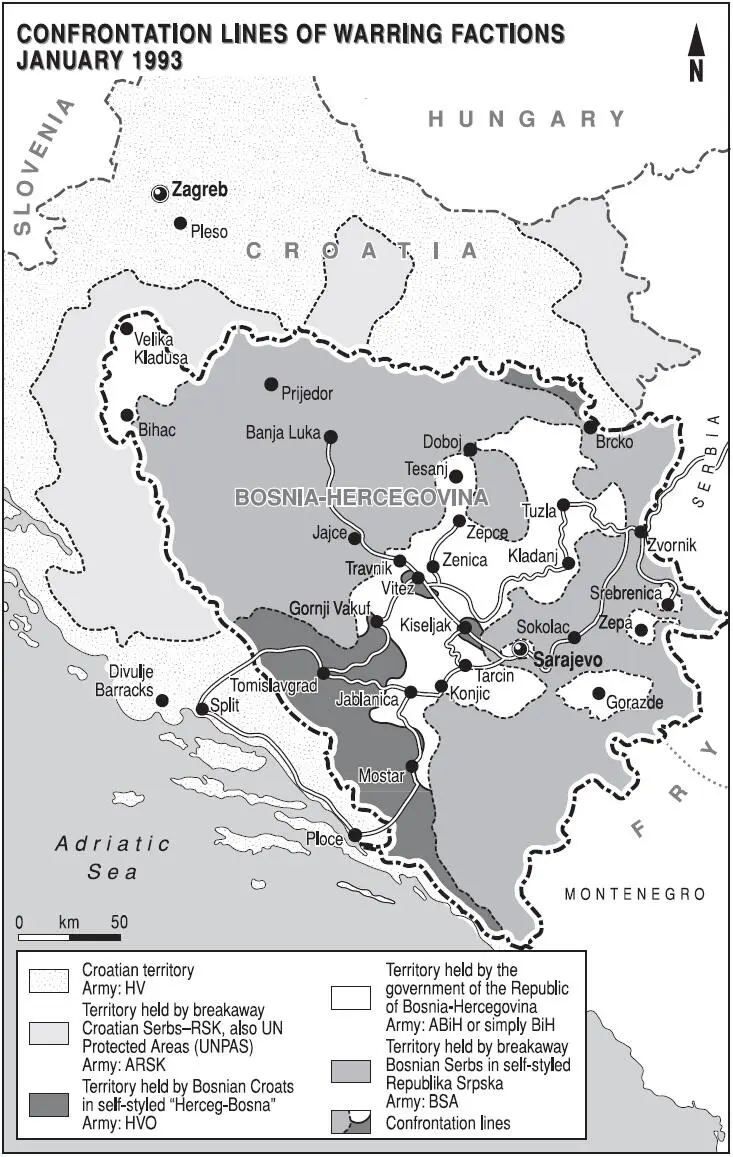

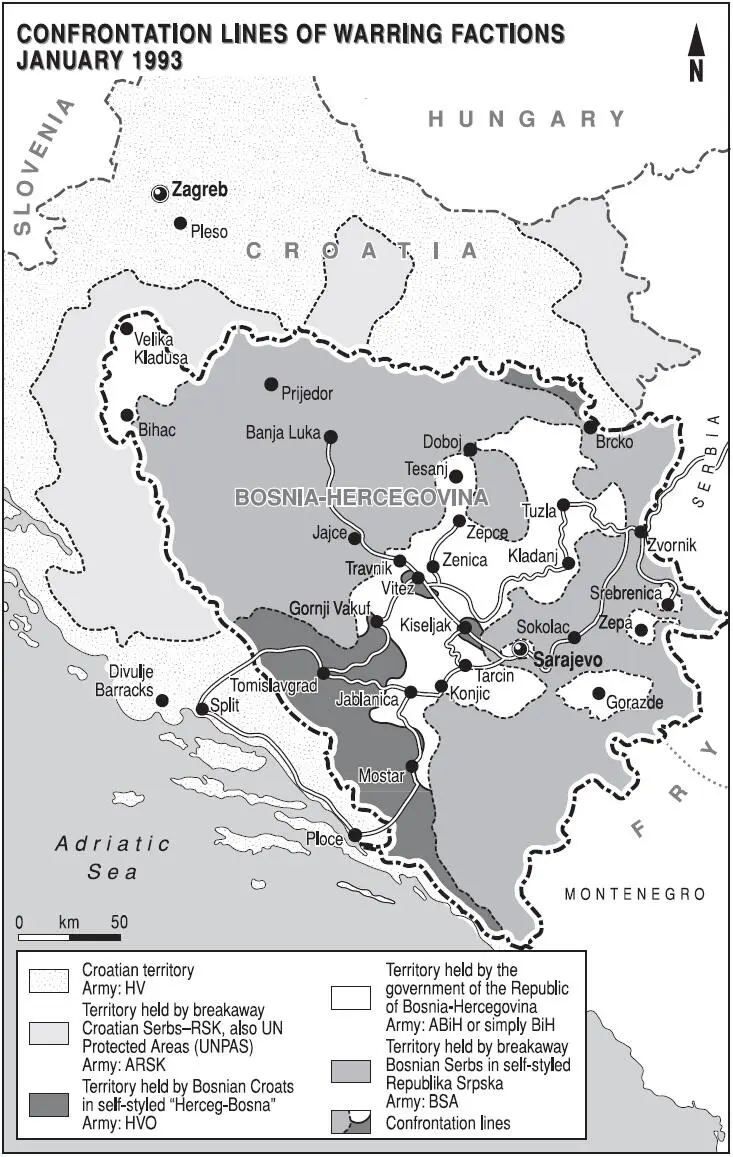

We’d been in Vitez that morning. In fact we’d just left the Cheshire Regiment’s camp at Stara Bila when it happened. We’d driven there from Brigadier Cumming’s tactical headquarters in the hotel in Fojnica. He’d been incensed by an article in the Daily Mail , written by Anna Pukas, which had glorified the British contribution to the UN and had damned, by omission, everyone else’s. We’d dropped by the Public Information house in Vitez late the previous night after a gruelling eleven-hour trip up into the Tesanj salient. Cumming had returned to the Land Rover Discovery clutching a fax of the article. He’d been livid but it had been too late to do anything about it at that hour so we’d returned to Fojnica. The following day we shot back to Vitez where Cumming had words with the Cheshires’ Commanding Officer, Lieutenant Colonel Bob Stewart, who had been quoted in the article.

We were heading back to Fojnica and had been on the road some ten minutes. The Brigadier was silent. Corporal Fox was concentrating on keeping the vehicle on the icy road and the accompanying UKLO team – an RAF flight lieutenant called Seb, his driver, Marine Dawson, and their wretched satellite dish in the back of their RB44 truck – in his rear-view mirror. Next to his pistol on the dash the handset of our HF radio spluttered and hissed into life. It was always making strange noises and ‘dropping’ so I never paid much attention to it. Corporal Fox grabbed it and stuck it to his ear.

‘Sir, I’m not sure, but it sounds like something’s going on in TSG … signal’s breaking up and I can’t work out their call sign … sounds like they’re being shelled or are under attack.’ Corporal Simon Fox was a pretty cool character, never flustered, always the laconic Lancastrian. I couldn’t make much sense with the radio either. Static and atmospherics were bad. All we could hear was a booming noise in the background. We decided to head back to Vitez.

The Operations Room at Vitez was packed. We entered to a deathly, expectant hush as everyone strained to hear the transmissions from TSG.

‘… that’s forty-seven and they’re still landing … forty-nine, fifty … still incoming …’ There was no mistaking it: TSG was definitely being shelled and some brave soul was still manning a radio, probably cowering under a desk, and was giving a live commentary as each shell landed.

Читать дальше