This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it , while at times based on historical events and figures, are the work of the author’s imagination.

The Borough Press

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

Published by HarperCollins Publishers 2018

Albert Bonniers Förlag, Stockholm, Sweden. Published in the English language by arrangement with Bonnier Rights, Stockholm, Sweden

Emmy Abrahamson asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

Nichola Smalley asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of the translation

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

First published by HarperCollins Publishers 2018

Copyright © Emmy Abrahamson 2018

English translation © Nichola Smalley

Cover design Micaela Alcaino © HarperCollins Publishers Ltd 2018

Cover photographs © Shutterstock.com

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books

Source ISBN: 9780008222338

Ebook Edition © October 2017 ISBN: 9780008222369

Version: 2017-12-21

Table of Contents

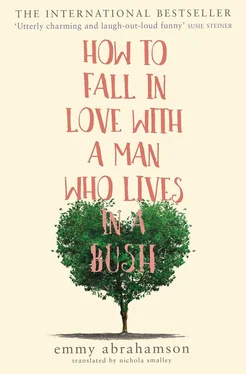

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Author’s Note

Questions for Further Discussion

A Conversation With Emmy Abrahamson

Being the Man in the Bush

About the Author

About the Publisher

‘I love cock!’ the woman says cheerfully.

I look down at my notes, scribble something illegible, place the ballpoint on the table and clear my throat.

‘What you’re trying to say … I think … or I hope … although I’m happy for you if you really feel that way … is perhaps that you love to cook. To cook . Not … cock .’

It’s the eleventh lesson of the day, and I’m so tired I’ve started rambling. What’s more, I’ve spent the whole time looking down at my mint-green information card to remind myself what the student’s name is. Petra Petra Petra . Worryingly, I also notice that I’ve taught this student at least three times before. And yet I have no memory of her. It’s as though all my students have turned into a single, faceless blob that’s unable to distinguish between Tuesday and Thursday, and stubbornly refuses to use the perfect tense. A blob that continues to say ‘Please’ in reply to a thank you, despite my hundreds of reminders about saying ‘You’re welcome’. A blob that believes language learning is a process that occurs automatically as long as you’re in the same room as a teacher. With a quick glance at the clock I realise there are still another twenty minutes till the lesson is over. Twenty minutes of eternity.

‘And, er … Petra, what kind of food do you like to cook?’ I ask.

It was never my dream, or plan, to become an English teacher. But after four months’ unemployment, the advert saying that Berlitz was looking for teachers was almost too good to be true. The training course was only two weeks long, and as soon as we were finished we could start teaching. Even so, I spent the first few weeks glancing at the door and expecting the ponytailed guy who’d run the course to come rushing in and breathlessly exclaim: ‘It was only a joke. Of course you’re not allowed to teach. We were just having a laugh!’ before throwing me out onto the street and escorting the student to safety. That was when I was still sitting up late every evening preparing the next day’s lessons. I carefully drew up lesson plans, making sure each class was varied and entertaining. I made copies of interesting articles, wrote down questions, drafted inoffensive role plays and laminated photos that would lead into relevant themes for discussion. All to get my students speaking as much English as possible.

Now they’re lucky if I even glance at their information cards before entering the room. This minor rebellion on my part started the day I realised I’d been teaching for significantly longer than the six months I’d planned and – even worse – that I was good at it. I was both patient (who’d have thought that would be the main ingredient for a good language teacher?) and had a knack for getting my students to speak English. Now that I’ve stopped planning my lessons and they’ve become a mystery to both me and my students, life has become a bit more exciting.

‘Oh, everything. Schnitzel, sausages …’ says Petra.

‘Complete sentences,’ I say, encouragingly.

‘I like to cook schnitzel and sausages,’ Petra says obediently.

Because the basic rule of the Berlitz method is that you can learn a language through everyday conversation, I can keep a lesson going for as long as I can come up with things to talk about. My three years as an English teacher have turned me into an expert in small talk. Once I got a student to talk about the lock he’d changed on his garage door for a quarter of an hour, just to see if I could.

‘And what’s your favourite drink?’ I ask.

Petra considers. ‘Tap water.’

‘Complete sentences,’ I repeat with a strained smile.

‘My favourite drink is tap water,’ Petra says.

I continue to smile at her, because I genuinely have no idea what to say to someone whose favourite drink is tap water.

For the final fifteen minutes, we do a cookery-themed crossword. When the bell rings I let out a little pretend sigh and turn down the corners of my mouth to show how sad I am that we have to finish. We shake hands, of course, and Petra disappears off home, probably to a dinner consisting of schnitzel and sausages washed down with a glass of tap water.

Everyone crams into the tiny staffroom so as to avoid any contact with the students during the five-minute break. On the walls there are Berlitz posters with multicultural faces and sentences followed by exclamation marks. The three bookshelves are full of Berlitz’s in-house magazine Passport and some Spanish, French and Russian textbooks that appear to be completely untouched. The English books, on the other hand, are so battered that most of them are missing their spines or are held together with tape.

None of the Berlitz staff are real teachers. Mike’s an out-of-work actor, Jason’s finishing his PhD on Schönberg, Claire used to work in marketing, Randall’s a graphic designer, Sarah’s a civil engineer, Rebecca’s a violin maker, Karen has a degree in media and communication and I still dream of one day becoming an author. The only one who’s a trained teacher is Ken, so he’s hated almost as much as Dagmar, the administrator at our Berlitz branch on Mariahilferstrasse.

Читать дальше