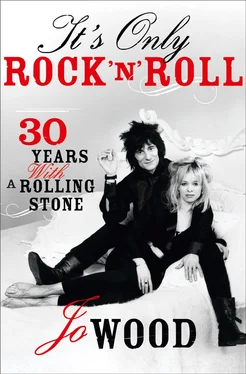

Right at the front, Ronnie was getting stuck into his solo. Oh, my honey! Seeing him on stage still gave me goose-bumps. Whenever there had been hard times, whether it was his alcoholism, drugs or other women, it was in moments like this that all the bad stuff was forgotten. I was married to a creative genius, there was no doubt about it.

But as the roar of the audience drowned the last notes of the song, I was suddenly struck by the intense conviction that this was the last time I would be standing there, watching the Stones. It was almost like a premonition. Make the most of this moment, Jo: you’re never going to experience it again. It hit me so unexpectedly, and with such force, that I was left quite emotional. Where the hell did that come from? It must have been because it’s the last show , I thought. But, no, it was definitely more than end-of-tour blues. It was a feeling – a certainty – that everything was about to change; that my life would never be the same again.

If you had said to me at that moment that actually my premonition had been spot on and that I would never experience the thrill of touring with the Stones again, I probably wouldn’t have been that surprised. I was in my early fifties; I was a granny. I had no regrets – after all, I’d been there, done that and got the T-shirt. Having clocked up 30 years on the road alongside the Rolling Stones, I’d designed the bloody T-shirt!

No, what would have shocked me – in fact, what would have absolutely devastated me – would have been to know that in less than a year’s time I would have lost Ronnie. My world, my love, my everything.

‘Ladies and gentlemen,’ cried the circus ringmaster, ‘the moment you’ve all been waiting for! Prepare to be amazed by the Fabulous Flying Josephine!’

I stood on my bed, waving at the crowd below, then took a deep breath and launched myself onto the trapeze. I flew through the air in a series of death-defying spins and landed gracefully on the ground as the audience went wild.

‘Thank you, thank you!’ I bowed, graciously acknowledging their cheers.

I picked up Bella, my favourite doll, who was that day playing the part of the ringmaster, and waved her arm at a couple of teddies.

‘And now, bring on the clowns!’

I’ve always been a daydreamer. As a little girl I spent most of my time living in a fantasy world. I’d see something on TV or read a story and my imagination would run riot. As well as the circus phase, there was the time I saw a film about a little girl who wanted to be an actress and dreamt of ‘seeing her name in lights’. From then on I was obsessed. One day, my name will be in lights, too! If Britain’s Got Talent had existed I’m sure I’d have been first in line for the auditions. Seeing as I can’t really sing and – as viewers of the BBC’s Strictly Come Dancing will vouch – have two left feet, I’m not sure what my talent would have been, but I doubt that would have stopped me having a go.

My mum did everything she could to feed and encourage my overactive imagination. I’d find tiny letters hidden about the house from Tinker Bell, postage-stamp-sized envelopes containing a note written in tiny fairy writing: ‘Dearest Josephine, Mummy tells me you’ve been very helpful this week …’ One day I came home from school to discover all 20 of my dolls lined up on the bed dressed in identical knitted jumpers and stretchy ski-pants. Mum must have been buzzing away on her sewing-machine for months, but to me it was as if it had happened in the wave of a magic wand. She had a real fairytale touch when I was growing up – and still does to this day.

Mum – Rachel Ursula Lundell – was born in 1934 in the heat and dust of South Africa’s Eastern Cape, in a tiny village called Tsolo. My grandfather, George, was a Dutch builder, while his wife, Ellen, was the granddaughter of a woman of the Xhosa-speaking Pondo tribe. Ellen was the last of seven children and my mum, too, was the youngest of seven. According to folklore, the seventh daughter of a seventh daughter is capable of great magic, and Mum has always been convinced by her ‘powers’. She will tell you about the time she cured the local butcher of his warts and healed her neighbour’s eczema with just a touch. But whether or not Mum really does have supernatural powers, I definitely think there’s something a little bit magical about the story of how this young African girl ended up travelling to the other side of the world and falling in love with my dad, who lived in leafy Surrey.

From a young age, Mum had a headstrong streak. She was sent to a convent boarding-school, where she got up to all sorts of naughtiness. She once broke into the convent pantry with her friend, Audrey, and the pair smuggled some sugar out in their bras. Weeks later, by the time the nuns broke up the racket, Mum and Audrey had turned professional, taking orders and selling the sugar to friends. Mum got 16 lashes with the sjambok , a heavy leather bullwhip. She’s still got the scars, but she reckons it cured her sweet tooth for good.

When she was 12, a witch-doctor read her fortune and told her she would travel overseas, but it wasn’t until she was 17 that something happened to seal the deal. By this time South Africa was in the grip of apartheid. The population was segregated by skin colour: black, white or – in Mum’s case, as she was mixed-race – coloured. Shortly after leaving school she applied for a typist’s job in a bakery where her brother, Desmond, was already working. The bakery woman couldn’t have been nicer to the pretty, golden-haired girl with the Dior-style lace dress and quickly offered her the position, but just as they were walking to the door, Mum spotted Desmond and waved to him.

‘Do you know that man?’ the woman asked her.

‘Yes, he’s my brother,’ said Mum.

The woman stared at her. ‘I’m sorry,’ she said quickly, ‘but I can’t give you the job.’ She hadn’t realized that Mum wasn’t white.

In 1951 Rachel waved goodbye to Africa and went to England to stay with her sister, Joan, who was living in Surbiton with her English husband, a press photographer named Tony Booker, and got a secretarial job with the Milk Marketing Board. By now, she had grown into a very beautiful young woman – and had left a few broken hearts in South Africa. Shortly before leaving for England she had been working at her auntie’s grocery in Umtata and one of the local lads would come by every week on the pretence of buying a few bits and pieces so he could stare at her. Then one day he handed her a love letter. ‘Lots of garbage about how lovely I was,’ is Mum’s typically no-nonsense memory of it. It was a shame she didn’t keep the letter as it was signed ‘Nelson Mandela’.

A year after she’d arrived in England it was Mum’s turn to fall madly in love. She was helping Joan in the garden when a friend of Tony’s, Michael Karslake, stopped by. That evening, Michael – six foot two, with thick dark hair and a lovely smile, according to Mum – took her to the cinema. She can’t remember which film was on because they snogged the whole way through it.

It was love at first sight for my dad, too. Born in 1932 in Surrey, Michael Howard Karslake was working as an architectural model-maker, after an apprenticeship at the London County Council’s model-making department. He proved incredibly gifted at his chosen career. Nowadays, the intricate architectural models he built – ranging from the Thames Flood Barrier to a prototype helmet for racing driver Stirling Moss – would be created on a computer, but back then no project could do without the kind of skills he possessed.

Читать дальше