We see a strong working memory giving us an advantage at play in many aspects of everyday life too. It allows you to listen to your spouse while checking your smart phone and making pancakes for the kids. It lets you complete a complicated spreadsheet in spite of interruptions from your constantly ringing phone and the din of annoyingly loud coworkers. Working memory gives you the ability to remain focused on the conversation with your dinner date while ignoring the urge to check the hockey score on your mobile.

Working Memory in the Brain

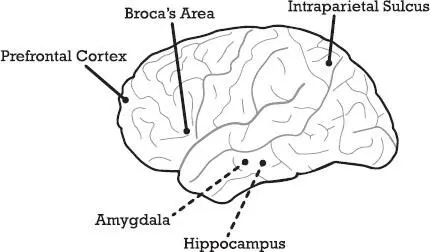

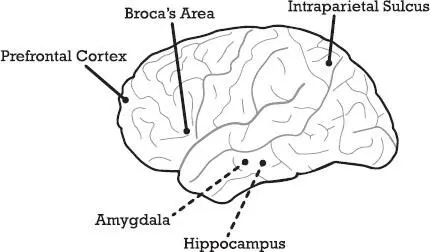

For more than the past decade, scientists have been using advanced brain imaging to examine how working memory functions in the brain. Their results reveal that using working memory involves a number of areas in the brain. On the next page are some of the major players:

Major Players in Working Memory

Prefrontal cortex (PFC) : The PFC is the home of working memory. Located in the front of the brain, the PFC coordinates with other areas of the brain through electrical signals and receives information from those regions so your working memory can make use of it. Brain-imaging scans show that when working memory is being used, the PFC glows while it fires thoughts to and works with information from the different brain regions. Working memory is the primary function of the PFC. Though the PFC is the area most often associated with working memory, it is important to note that scientists have also found activation in other areas of the brain, such as the parietal cortex and the anterior cingulate, when people perform a working memory task.

Hippocampus : The hippocampus is where the vast amount of knowledge you have acquired over your lifetime is housed for long-term storage. It is the location of long-term memory (LTM). Your working memory allows you to sift through all the information you have stored in your long-term memory, and pull out the bits most relevant to the task at hand. It gives you the ability to combine that stored knowledge with new information coming in, and to put new information into your long-term memory.

Amygdala : The amygdala is the brain’s emotional center. When you are experiencing a strong emotion, like fear, your amygdala is activated. Working memory is also important to emotional control, managing the emotional information coming from the amygdala and preventing it from distracting you from the task you’re working on. If someone yells “Fire!” in the cinema, your working memory would help you to control the fear coming from your amygdala so that you can exit in an orderly fashion without creating a panic.

Intraparietal sulcus : Located at the top back portion of the brain, the intraparietal sulcus is the brain’s math center. When you need to perform calculations, such as in choosing the best mortgage loan or guesstimating how many more miles you can go on a quarter tank of gas, your working memory relies on it to get the answer. In fact, the intraparietal sulcus is so important to math skills that when researchers used mild electrical currents in order to take it offline, participants struggled to perform simple math tasks, like deciding whether 4 was bigger than 2.

Broca’s area : Situated on the left side of the frontal lobes, Broca’s area is involved in language comprehension and verbal fluency. Whenever you are writing or interacting with friends, family, colleagues, or a love interest, your working memory is processing information sent from this area. Whether you are a quick-witted verbal gymnast or you tend to stumble over your words depends in part on the strength of your working memory. We recently saw this play out at a wedding when the best man stood up to give the toast and then realized he had left his notes in the car. Instead of stumbling over a bunch of “ums” and “uhs,” his working memory and Broca’s area worked together to help him craft an eloquent, heartfelt toast on the spot.

What Working Memory Is Not

Whenever we give a presentation about working memory, someone in the audience raises his hand and asks, “Isn’t that the same as short-term memory?” The answer is an unequivocal no . Short-term memory is the ability to remember information, such as someone’s name at a party, this person’s occupation, or the title of a recommended book, for a very short period. We usually don’t keep this information in mind for long—a few seconds or so—and we would typically struggle to recall that person’s name or the book title the following day. Working memory gives us the ability to do something with the information at hand rather than just remember it briefly.

Let’s say you’re at a business event and you meet Keith, a small-business consultant who mentions that anybody trying to start a business absolutely must read The Essential Entrepreneur by Smarticus McSmarty. You instantly recall that your friend Theresa is thinking about launching a new business venture, and you jot down the book’s title so you can send her a text about it later. Your working memory is what helps you recall, from long-term memory, that Theresa wants to start a business and combine that with the new information that the book is great for entrepreneurs.

Working memory is also different from long-term memory. Long-term memory is the library of knowledge you have accumulated over the years—knowledge about countries, information about random news facts, memories about events from your school days, and even those annoying advertising jingles you heard on TV when you were a kid. Information may remain stored in your long-term memory for anywhere from a few days to many decades.

Working memory is what allows you to access that information and put it to good use. You can pull out information from your long-term memory, use that information in the moment, and then file it away again. Working memory is also the mechanism used to transfer new information into long-term memory, as when you are learning a new language.

Working Memory as a Conductor

You can think of working memory as your brain’s Conductor. A conductor of music brings all the different instruments of an orchestra under control. Without the conductor, the result is a cacophony: the piccolo might tweet when the piano was supposed to play or the violins might be drowned out by a thundering percussion section. When the conductor walks out on the stage, chaos is brought to order.

In a similar way, your working memory gives you the advantage of control over the daily information onslaught: the emails, the ringing phones, the schedule that is constantly changing, the new math lesson that must be learned, your friend’s disheartening Facebook update, the Twitter updates, the presentation that must be rapidly assembled for a potential client. In this ocean of information, where everything seems to be equally important, your working memory Conductor has two main functions:

1 It prioritizes and processes information, allowing you to ignore what is irrelevant and work with what is important.

2 It holds on to information so you can work with it.

Throughout this book, we occasionally refer to working memory as the Conductor , or the working memory Conductor , when discussing these functions.

For an illustration of how the working memory Conductor can give you an advantage at work, imagine for a moment that you are Mark, a middle manager in Microsoft’s Tablet PC division, and the Tablet has been taking a beating from the iPad 700, which projects holograms. iPad 700 users love seeing their pictures and spreadsheets in three dimensions. You’re called to a meeting where an inventor takes out a tablet called the FeelPad that can give holograms mass. FeelPad users can project images that can be touched and felt, not just seen. You are truly amazed. And because you are lower down the pecking order, you can just sit back and be enthralled because no one ever asks you a question at these meetings. Until today.

Читать дальше