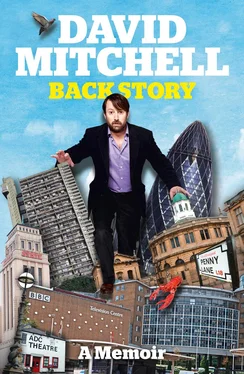

The Fawlty TowersYears Contents Cover Title Page Dedication For VC (M) Introduction 1 The Fawlty Towers Years 2 Inventing Fleet Street 3 Light-houses, My Boy! 4 Summoning Servants 5 The Pianist and the Fisherman 6 Death of a Monster 7 Civis Britannicus Sum 8 The Mystery of the Unexplained Pole 9 Beatings and Crisps 10 The Smell of the Crowd 11 Cross-Dressing, Cards and Cocaine 12 Presidents of the Galaxy 13 Badges 14 Play It Nice and Cool, Son 15 Teenage Thrills: First Love, and the Rotary Club Public Speaking Competition 16 Where Did You Get That Hat? 17 I Am Not a Cider Drinker 18 Enthusiasm in Basements 19 God Is Love 20 The Cause of and Answer to All of Life’s Problems 21 Attention 22 Mitchell and Webb 23 We Said We Wouldn’t Look Back 24 The Lager’s Just Run Out 25 Real Comic Talent 26 Going Fishing 27 Causes of Celebration 28 The Magician 29 Are You Sitting Down? 30 Peep Show 31 Being Myself 32 Lovely Spam, Wonderful Spam 33 The Work–Work Balance 34 The End of the Beginning 35 Centred Picture Section Copyright About the Publisher

Anyone watching me lock my front door would think that I was trying to break in: frantically yanking the handle up and down, pulling it hard towards me and then pushing against the frame with a firmness that’s just short of a shoulder barge. Then running round to the kitchen window and furtively peering in. In fact I’m checking that the door’s properly locked and then that the gas is off. This is the wrong way round but I’m relatively new to having gas and so the neuroticism about it kicks in marginally later than my door doubts, which date from having a locker at school.

I never had anything of any value in my locker – not so much as a Twix. But the fact that it was lockable meant it should be locked, meant that I had to remember to lock it, meant that I had to check that it was locked, meant that I had to remember if I’d checked that it was locked.

That was the advent of my school-leaving dance (by which I mean the odd routine I put myself through every day before going home, not a sort of prom; my school didn’t have a prom, it was in Britain – in fact it had a ball; I didn’t go). The steps were: locking my locker, checking it absent-mindedly, walking out of the room, pausing unsure whether I’d checked it, returning to the locker, annoyed the whole way about the time I was almost certainly wasting; approaching the locker with such a complete expectation that it was locked that my mind wandered and I barely noticed myself check it so that when, moments later, I was leaving the school again, I wasn’t one hundred per cent sure that I’d checked it or that, in that moment of complacent absent-mindedness, I’d have noticed if it wasn’t locked; turning back again.

To say that this could go on for hours would be an exaggeration but it could take a quarter of an hour. In time I learned that the key was to concentrate when checking the locker. Take a mental photograph of the moment. Say to myself: ‘Here I am, now, me, sane, with a locked locker. Remember this in the doubting moments to come.’

But the concentration is tiring so, having gone through it with the door today, I’m unwilling to unlock it to go and check the gas when, by peering through the window, I can probably check the alignment of the hob knobs. (I wonder if that’s where the biscuit got its name. I’m suspicious about that biscuit’s name. It’s like Stinking Bishop: recent, yet quickly adopted as a go-to reference for those wishing to be cosily humorous. It got its Alan Bennett licence too early and easily. I suspect the advertising agency was involved.)

I adjust the collar of my jacket, massaging a slightly jarred wrist from my high-energy security check. It’s a spring day and slightly too warm for a jacket really – certainly once I get walking. Unless the temperature is absolutely Siberian, a brisk walk always warms me up, especially when I’ve got a jacket on. Or at least warms up the middle of my back, which then sweats through my shirt. So I have to wear a jacket to hide that.

My walk begins on the exterior staircase from my flat, which I have to descend carefully in case there’s sick or a used needle. Listen to me, glamorising the place! There’s never sick or a needle! This is Kilburn, not Harlesden. I mean wee or a bit of cling-film from one of those little cannabis turds. Sometimes some kids are sitting at the bottom. One of them might say: ‘Hey, are you the guy from Peep Show ?’ I am, so I nod.

I don’t know how I ended up in Kilburn. I’m not from here – but then hardly anyone who lives in London is from there. I think it’s slightly weird to be from London. As a child, London terrified me, largely because I considered it to be the British manifestation of New York which, on television, looked like a living hell. I think I’m largely basing this on Cagney and Lacey, who seemed to have a horrible time. It was all drugs and crowds and scruffy offices and huge locks on the inside of apartment doors.

The size of those locks was unnerving. Who or what were locks that sturdy and that numerous meant to keep out? And by the time such a gang or monster, or drug-addled gang made monstrous by their craving, was bashing on the door, you might as well just open it and hope they kill you quickly, because what’s the alternative? Escape via the garden? Oh no, no one has a garden. There’s a park you can get to on a frightening underground train full of junkies, and where you can maybe play a bit of frisbee while old ladies are raped in the bushes around you, but this is a world without gardens, without swingball and where it certainly isn’t safe to ride your bike with attached stabilisers along the pavement.

That’s what I assumed London was like. My childhood self would hate where I live now. He would also be disappointed that I’m not ruler of the world or at least Prime Minister or a wizard. But the fact that, far from a castle, mansion or cave complex, I don’t even live in a normal house with a garden and an attic and a spare room would basically make me indistinguishable, to his eyes, from a tramp.

Growing up, there were metaphorical stabilisers attached to my whole life. Born in Salisbury, brought up in Oxford and a student in Cambridge, I was 22 before I had to deal on a daily basis with anywhere other than affluent, ancient, chocolate-box cities where murders never happen but murder stories are often set. I was cosseted in deep suburban security and probably fretted about the outside world all the more as a result.

I have often suffered from the fact that warnings are calibrated for the reckless. Very sensibly, parents, teachers and people at TV filming locations who provide you with blank-firing guns for action sequences (to pick three random types of authority figure) design their remarks to prevent the fearless from accidentally killing themselves. ‘Don’t look at the sun or you’ll go blind’ … ‘A blank-firing gun is an incredibly dangerous weapon’ … ‘Verrucas can kill.’

The collateral damage is every last scrap of more timorous people’s peace of mind; the sum of their warnings makes people like me view life as a minefield. So my childhood, as I remember it, was laced with fear.

But, before I can remember, there was definitely a moment of recklessness – when I pushed at the stabilising boundaries that my doting parents had set for me. This was in Salisbury – in fact a little village just outside called Stapleford where we lived in a bungalow. I couldn’t walk but I did have a sort of walker – a small vehicle with a seat and wheels, but no engine, that I could propel along, Flintstones-style, with my bare feet. Having mastered this contraption, I apparently became unwilling to learn to walk properly but would career around in it at high speeds.

Читать дальше